By David G. Clohessy

Volunteer Director of Missouri SNAP

May 27, 2024

Twenty-five years ago, Eric Patterson of Conway Springs, Kansas, took his own life. He had no way of knowing, of course, that his horrific pain and desperation would transform his quiet schoolteacher mom into an incredibly powerful advocate for tens of thousands of victims of child-molesting clerics and their corrupt supervisors.

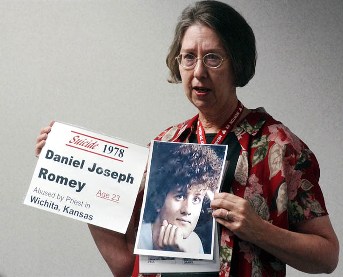

Eric had been sexually abused at age 12 – “practically raped,” as he put it – by Fr. Robert Larson of the Wichita Diocese. So too were Daniel Romey, Bobby Thompson, Gilbert Rodriguez, and Paul Tafolla, all devout Catholic boys. In fact, all but Tafolla “dreamed of being priests one day,” according to one news account.

Each of them, between 1978 and 2000, committed suicide. In my 35+ years in this struggle to protect the vulnerable and heal the wounded, I don’t know of another predator priest who left such a trail of devastation.

And these boys weren’t Fr. Larson’s only victims. He ended up in prison not for having assaulted these five, but for his crimes against at least four others.

Eric’s mom, Janet, passed away this Spring. For two decades, she was the Kansas SNAP leader. She was on the SNAP board for years. While her voice was calm and her demeanor reasonable, Janet emanated an unshakable determination to save others from the overwhelming pain inflicted by clerics – both those who committed and those who concealed heinous crimes against children.

But even more noteworthy, to me at least, were these two enormous contributions.

First, Janet stepped up at the absolutely most crucial moment in our movement – in and throughout the intense media maelstrom that began in 2002 as journalists across the world began trying to emulate the Boston Globe’s ground-breaking investigative reporting on long-buried deceptions and manipulations and assaults on innocent girls and boys.

Second, over more than two decades in our movement, I believe that Janet generously and compassionately spent more hours on the phone listening to and supporting survivors, especially those disclosing and reaching out for help, than all but a tiny handful of us.

Starting in Dallas at the 2002 US bishops’ meeting, despite her still-fresh and unimaginable grief, Janet stepped up, speaking with passion and compassion, over and over again, to anyone who would listen, of the deep pain felt by her and her husband Horace. She patiently and effectively and compellingly explained how the horrors of child sexual abuse and institutional cover up devastate entire families.

Janet tirelessly responded to hundreds of journalists who were clearly drawn to her down-to-earth frankness and her undeniably moving story. See the page-one articles about Janet and her family by Stan Finger of the Wichita Eagle and Thomas Farragher of the Boston Globe. See also the print editions of the Eagle (1, 2, 3, with initial article) and Globe stories.

She didn’t just show up when the cameras were there. Later in 2002, she joined Peter Isely, Art Andreas, and several other survivors in Oklahoma City for the first meeting of the National Review Board (chaired by former Oklahoma governor Frank Keating). As always, Janet’s testimony was riveting. But our collective hearts sank when it became clear that no one on the panel found her words and experiences anywhere near as gripping as we did.

Often jaws would drop when Janet would utter blunt truths like “Pagan religions were criticized for having human sacrifices, but if we allow this to happen to our children, this is human sacrifice.”

Perhaps the most memorable conversation I had with Janet was our first one. It was around 1999 or 2000. Many times since, I’ve told her, “Janet, you just don’t realize the impact you had on me.” I’m not sure I ever conveyed it to her adequately, but I’ll try again with you now.

For much of the mid- and late 90s, Barbara Blaine and I, and others in SNAP, were deeply frustrated and pessimistic. It felt like we were tilting at windmills, wildly popular and incredibly powerful windmills, windmills to which much of society felt nothing but respect, showing almost unquestioning deference to Catholic officials and institutions.

When it came to reports about child-molesting clerics, precious few noticed and even fewer seemed to care. After a decade of toiling ineffectually in what felt like complete obscurity, Barbara and I were at our most hopeless point.

One night I got a call from a number I didn’t recognize. I almost didn’t pick up. I recall thinking: “No doubt yet another deeply wounded and depressed survivor.” By that point, after ten years in SNAP, I’d taken hundreds of these calls and had grown increasingly despondent, call by call, because other than a sympathetic ear, I felt we had so little to offer so many in such pain.

Maybe it was guilt. But whatever the reason, I picked up the phone. Janet’s experience felt crushing. I’d never heard a more stunning story. I’m not sure I have heard one since.

We talked for two hours. Within minutes of hanging up, I was sobbing. But instead of being overwhelmed and paralyzed, Janet’s grief and strength inspired me. I realized I couldn’t ever walk away from SNAP.

The next day, I told Barbara about Eric and my conversation with Janet. We both resolved to stay in this struggle for the long haul.

My life of course is so much more rich, deep, and meaningful because Janet had the strength and courage to reach out to a stranger with a support group and launch herself into our collective battle.

Janet and Horace were among the very first parents of survivors to become deeply involved in our movement. And they did it with total grace and dignity. Along the way, they helped countless parents of survivors accept the fact that their child’s victimization was not their fault. They gently guided other moms and dads towards more productive ways of expressing their suffering and channeling their energies.

Of course, they weren’t the only brave, outspoken, and compassionate parents to get involved in our movement early. None of us will ever forget dear Pat and Lou Serrano of New Jersey, whose smart, courageous and eloquent son Mark was abused by a notorious Paterson diocesan serial predator priest, Fr. Jim Hanley. Pat and Lou remained in SNAP leadership for more than 12 years.

Janet, Horace, and Eric have never been far from my thoughts. Maybe it’s because I’m a father and can’t imagine my child being so deeply hurt by, much less losing a child because of, a predator. Maybe it’s also because Fr. Larson lived for a number of years at a church ‘treatment’ center for predator priests that’s maybe 20 miles from where my wife and I have lived for 20+ years. Fr. Larsen also spent time in Michigan, Maryland, Ohio and in Wichita, Pittsburgh, Independence, Haysville, Topeka, and Newton, all in Kansas.

Whatever the reason, despite their passing, Janet, Horace, and Eric never will be far from my thoughts. Hundreds of survivors and their loved ones feel the same.

Guest contributor David G. Clohessy is the former National Director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP) and is currently the volunteer director of Missouri SNAP. If you’d like to respond to David, please call him at 314-566-9790 (cell) or email him at davidgclohessy@gmail.com.

Images: Janet Patterson speaking at a July 29, 2004 meeting of the Kansas Parole board. She talked about Larson victim Daniel Romey, whose sister could not attend the hearing. The second photo shows Janet Patterson with her son Eric when he was a child. See her essay Hope, where the family photo was first published.