SPRINGFIELD (MA)

New England Public Media [Springfield MA]

February 4, 2025

By Nancy Eve Cohen

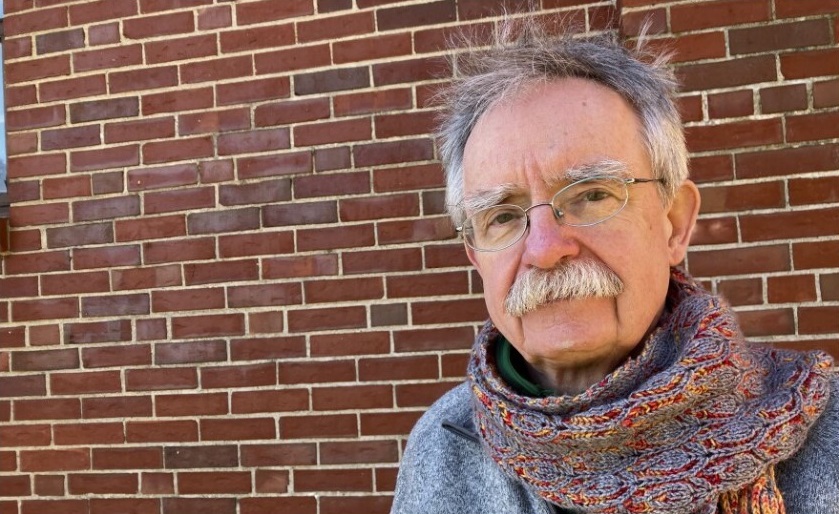

[Photo above: David Lewcon, 70, is a survivor of abuse at the Diocese of Worcester. He met with investigators from the Massachusetts attorney general’s office more than three years ago for their inquiry into sexual abuse of children at the Worcester, Springfield and Fall River dioceses, but he hasn’t heard from them since. Nancy Eve Cohen / NEPM]

Survivors of child sexual abuse in western and central Massachusetts have been calling on the state attorney general’s office to release its investigation into the Worcester, Springfield and Fall River Catholic dioceses.

But the office says it needs court approval to make it public.

Reports like this have been held up in courts in other states. When reports are released, some have made a big difference to victims.

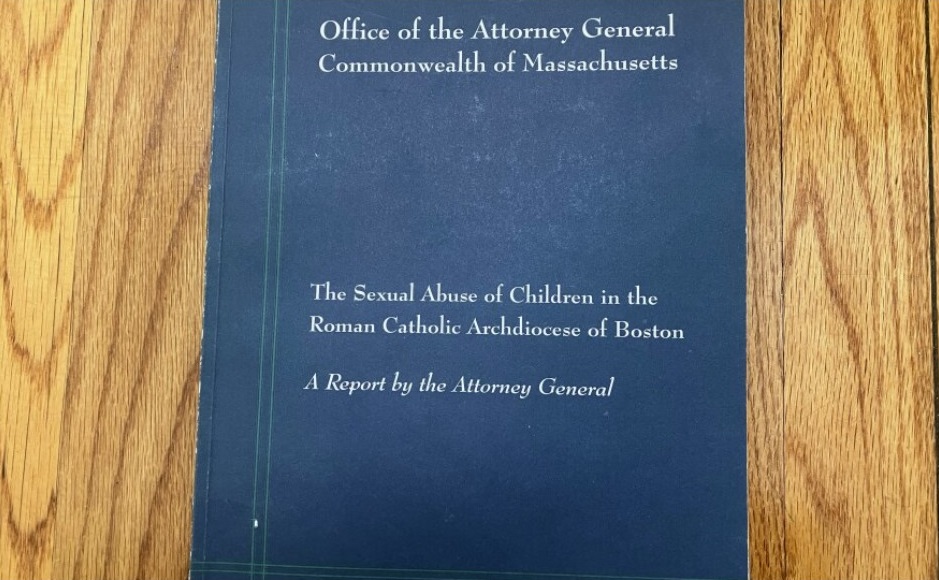

More than 20 years ago, Massachusetts Attorney General Thomas Reilly published an investigation into child sexual abuse at theBoston Archdiocese. It did not directly result in criminal charges, but concluded the leaders of the Archdiocese allowed the widespread abuse of children and did not report it to law enforcement.

Attorney John Stobierski, who has represented more than 100 survivors from the Springfield Diocese, said Reilly’s work caused significant change — in Boston

“Why doesn’t western Mass. deserve equal justice, equal attention that eastern Mass. has gotten? I don’t understand it. It doesn’t make sense to me,” he said.

Back when now-Gov. Maura Healey was attorney general, Stobierski said he wrote her several times asking her to investigate. When she did, sometime around 2019, he met investigators from her office more than once.

But the results from that investigation — which focuses on the Springfield, Worcester, and Fall River dioceses — have never been released.

In an interview on GBH Radio, the current attorney general, Andrea Campbell, said her office needs court approval before she can release it.

“I inherited this. And where it is, is in the courts. And I can’t say anything more,” Campbell said. “I want folks to know we’re not just sitting at the office doing nothing … with respect to ensuring there’s transparency on this issue.”

‘They wanted to cover up the cover-up’

Top prosecutors have published investigations like this in many places, including Maine, Michigan, Maryland and Pennsylvania.

When Pennsylvania’s attorney general at the time, Josh Shapiro, released the results of his investigation in August 2018, survivors — now adults — joined him on stage. The report identified more than 1,000 victims and 301 alleged perpetrators — Catholic priests.

But Shapiro, who is now Pennsylvania’s governor, said people implicated in the investigation went to court to try to stop it.

“These petitioners, and for a time, some of the dioceses, sought to prevent the entire report from ever seeing the light of day. In effect, they wanted to cover up the cover-up,” he said in that press conference.

Shapiro even wrote Pope Francis, saying he had planned to release the results of the investigation earlier, but a court had stopped its release.

“Credible reports indicate that at least two leaders of the Catholic Church in Pennsylvania — while not directly challenging the release of this report in court — are behind these efforts to silence the victims and avoid accountability,” Shapiro wrote.

Shapiro asked the pope to “direct church leaders … to permit the healing process to begin.”

In Massachusetts, Attorney General Campbell said she is not allowed to say who is stopping the release of her office’s report.

Terence McKiernan, president of the advocacy group Bishop Accountability, met with the the attorney general’s investigators in October 2021 and provided them with more than 1,500 pages of documents. He said, at the very least, Campbell should explain who is stopping the report.

“There’s certainly no reason pertaining to grand jury secrecy why that fact can’t be stated,” McKiernan said. “Instead, we’re getting … it appears politically motivated wariness about admitting any details at all here. And this is not about politics. This is not about Governor Healey looking good or [Attorney General] Campbell looking good. This is about the safety of children.”

Survivors who met with Massachusetts investigators want answers

David Lewcon, 70, was abused starting when he was 15 at St. Mary’s Parish in the Diocese of Worcester. He met with the attorney general’s investigators more than three years ago,but said he hasn’t heard from them since.

“It would be more fulfilling for me to realize that the information that I gave the attorney general’s office actually did some good. There’s a side of me that feels like it was sort of a waste of time,” Lewcon said.

Lewcon said a public record of crimes against minors would help victims and their families, who have also suffered. He remembers back in 1996 after he filed a lawsuit against the Worcester Diocese, a newspaper reported on it and his abuse became public.

He got a phone call.

“There was a man crying on the other side of the phone,” Lewcon said.

The man said he was also a survivor of abuse. The man’s girlfriend had seen the newspaper article, showed it to him, and said, “‘Now, I believe you,'” Lewcon recalled. “I heard from other people — the same thing. It was validating. It was information that was needed to be known. People could deal with it if it comes from a credible source.”

‘An expectation that the laws would change’

One of the earliest investigations by a credible source was conducted by former Philadelphia District Attorney Lynne Abraham. That 2005 report provided explicit detail about alleged sexual crimes by dozens of named priests against hundreds of children.

Mark Basquill, 63, who testified before a grand jury for that investigation, had been one of those children.

“To be officially acknowledged by law enforcement that this did happen and they were investigating it, that was actually a relief right there. It was like, oh my gosh, somebody recognizes what was going on and [they] can’t just play a shell game about it,” Basquill said.

Basquill said he was horrified to learn from the resulting public report that his abuser had more than a dozen other victims. And yet, Basquill said the act of testifying and later reading the report changed him — from victim to survivor.

Still, only one of the 63 priests named in the Philadelphia report was charged. No one was put behind bars.

“Because of the statute of limitations for many of the alleged perpetrators, many of whom simply admitted what they had done, that there was no realistic expectation of prosecution for the specific offenses. There was an expectation that the laws would change for future generations, at least when I testified,” Basquill said.

Laws did change. Charles Gallagher, the senior prosecutor of that Philadelphia investigation, said it led to extending the statute of limitations so victims had another 20 years, until age 50, to file a criminal complaint.

“So that law enforcement could go after older cases,” Gallagher said. “And we also changed the law to include stronger penalties for sexual abuse of children, and also expanded the realm of who could be charged with endangering the welfare of a child.”

The Archdiocese of Philadelphia also made changes. It began reporting abuse of children to law enforcement. Back then, investigators found the church had used loopholes in the law to avoid that.

Since the 2005 Philadelphia investigation, at least 17 other reports by top law enforcement officials have become public, according to Bishop Accountability.

But some get delayed by the courts. That happened when the Maryland attorney general wanted to release his office’s report, as Campbell noted on GBH Radio.

“He went through a process in order to be able to release certain information, even in redacted form,” she said. “We’re going through a similar process [in Massachusetts].”

A similar investigation is also held up in New Jersey.

‘Now the world knew I spoke the truth’

In Maryland, two days after Attorney General Anthony Brown released a redacted version of his office’s investigation into the Archdiocese of Baltimore, state lawmakers voted to eliminate the statute of limitations in child sexual abuse lawsuits.

“It was crazy. It was like a one-two punch to the church,” said Teresa Lancaster, 70, a Maryland attorney who represents survivors.

Lancaster is also a survivor. She said she was abused by a priest — her guidance counselor — in 1970, when she was 16. When she filed a lawsuit decades ago, she was told she was making it up. But when the attorney general’s report became public, she cried tears of joy.

“It validated everything I had said all along. And now the world knew I spoke the truth,” Lancaster said.

That Maryland law eliminating the statute of limitations is on hold. The Roman Catholic Archbishop of Washington and others are challenging its constitutionality in the state supreme court.

In addition, the Archdiocese of Baltimore declared bankruptcy two days before the law allowing more lawsuits would have gone into effect.

But in Michigan, an investigation into all the dioceses in the state has led to prosecutions. So far, Attorney General’s Dana Nessel’s office said it secured convictions in nine cases involving 38 survivors.

More often, though, prosecutions don’t happen.

Cyndi MacKenzie led support groups in Maine for survivors of abuse by priests there. And she provided records to the Maine attorney general for a 2004 investigation of allegations from survivors.

“They felt vindicated. They felt heard, but they didn’t feel like the law was ever going to stop the powerful church — no matter how high it went, all the way to the attorney general, no one was arrested for molesting children. That’s something that, as a survivor, all of us don’t understand,” she said.

MacKenzie is herself a survivor of abuse at Notre Dame Church in Southbridge, Massachusetts, where she said her parish priest sexually abused and raped her, starting when she was 4.

![A photograph of Cyndi MacKenzie at age 4 or 5, around the same time she was sexually abused by her parish priest in Southbridge, Massachusetts. "As long as the attorney general in Massachusetts doesn't release this report [on abuse of children at Catholic dioceses], they are protecting the church and not the survivors," MacKenzie said. Submitted / Cyndi MacKenzie](https://www.bishop-accountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/c-2025-02-04-Cohen-Investigations-ph-Cyndi-MacKenzie-age-4-or-5.jpg)

MacKenzie said she was not contacted by the attorney general’s office for its investigation into the Worcester Diocese, but she said other survivors entrusted the investigators to do their job.

“As long as the attorney general in Massachusetts doesn’t release this report, they are protecting the church and not the survivors,” MacKenzie said.

Asked to comment, a spokesperson said Campbell and her office “are bound to rules of law that do not allow us to publicly comment on our efforts to release the report.”

The Fall River, Springfield and Worcester dioceses did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Neither did Gov. Healey’s office.

Nancy Eve Cohen is a senior reporter focusing on Berkshire County. Earlier in her career she was NPR’s Midwest editor in Washington, D.C., managing editor of the Northeast Environmental Hub and recorded sound for TV networks on global assignments, including the war in Sarajevo and an interview with Fidel Castro.See stories by Nancy Eve Cohen