CHICAGO (IL)

Chicago Sun-Times [Chicago IL]

April 19, 2024

By Robert Herguth

The Catholic church’s transparency on accusations of sexual abuse by clergy members, including the Rev. Mark Santo, remains inconsistent and lacking across the United States, clouding the extent of the crisis more than 20 years after it exploded into view.

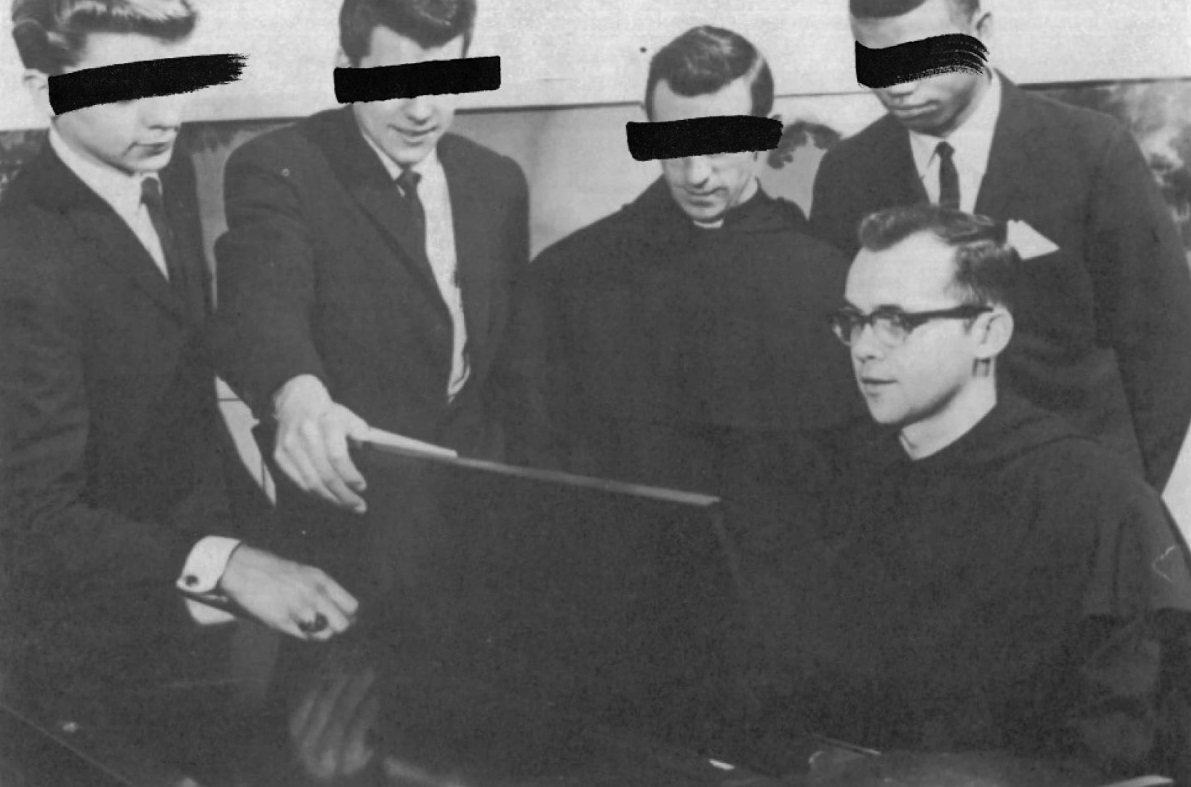

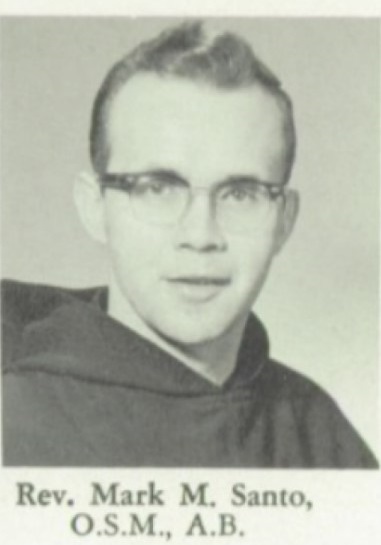

As a new Catholic priest in Chicago in the early 1960s and member of the church’s Servite order, the Rev. Mark Santo taught religion and oversaw the glee club at a parochial high school on the West Side.

Later, he helped run several parishes — in a tiny Missouri town, in Detroit and Rochester, Minnesota, and for a number of years on the Near North Side not far from the Cabrini-Green public housing development.

For a time, he also was the director of prison ministry for the Archdiocese of Miami — the arm of the church for part of South Florida — and a chaplain at federal lockups in Michigan and Los Angeles.

At one point, he joined the Archdiocese of Milwaukee and, at the time of his death in 2008, apparently had been living in Toronto.

Somewhere along that wide swath of assignments and cities, he allegedly sexually abused a child, records show.

But it’s virtually impossible to find any information about that — including where any misconduct occurred, when, how the church learned of it and whether there were any repercussions for Santo.

Of the nine Catholic jurisdictions in the United States where he’s known to have ministered and lived, just one has his name in a public listing of clergy sex offenders: the Diocese of Springfield-Cape Girardeau in rural southern Missouri, records show. And that shows only his name, the parish where he served and that he’s dead. An earlier version of that list had said the abuse occurred in the 1960s.

Seven of the nine jurisdictions where Santo served have their own public listings of clergy deemed to have been credibly accused of sexual abuse. Several church officials say Santo wasn’t on their public logs because they didn’t know about the accusations against him but might now add his name to their lists.

Two of those nine jurisdictions maintain no public listings. They include the Servite order, whose leaders are based in Chicago. Officials with the Servites won’t talk about Santo’s assignment history or any misconduct.

Santo’s story offers a stark illustration of how, more than 20 years after the church’s sex abuse crisis exploded into public view in the United States, the Catholic church remains mired in secrecy about the extent of the scandal despite promises of transparency and reform.

A trail of secrecy

- The Rev. Mark Santo lived or ministered in at least nine U.S. church jurisdictions but appears on just one public list of credibly accused clergy.

- Seven of those nine jurisdictions maintain public lists, but they vary in what they include because there are no uniform church rules or standards on transparency.

- Neither the Servite religious order that Santo belonged to nor the Archdiocese of Miami where he ministered for years maintain publicly available lists of credibly accused clergy.

- Santo served for years in Chicago, but Cardinal Blase Cupich’s office won’t say why he’s not on his local list of clergy offenders.

- Santo not only served in the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, he was accepted into the jurisdiction after leaving the Servites. But he isn’t on Milwaukee Archbishop Jerome Listecki’s list either, and his aides won’t say why.

- The pope lets dioceses and religious orders decide how — and whether — to disclose their predatory members in lists, and the end result is an incomplete and inconsistent accounting.

Most geographic arms of the American church — dioceses and the larger archdioceses — now maintain public listings of child-molesting clergy in the name of healing and penance and sometimes as a condition of lawsuits or bankruptcy court rulings.

And many of the 200 or so Catholic male religious orders in the United States also maintain online lists of their clergy deemed to have been credibly accused of sex abuse.

Santo’s start in the Servites

But, because Pope Francis lets bishops and order leaders decide whether to post their own lists of predatory clergy and, if so, how much information to reveal, the result is an incomplete and inconsistent accounting, the Chicago Sun-Times found.

Santo was born in Milwaukee in 1933 and made his “solemn profession of vows” in 1957 in Lake Bluff, where the Servites used to have a college seminary, according to his death notice and other records.

He was ordained a Catholic priest in Chicago in 1960 with the order — whose full name is the Order of Friar Servants of Mary. The group of priests, religious brothers, nuns and others was founded in Italy in the 1200s. It says its focus is “serving the church and humanity, drawing inspiration from St. Mary at the Cross,” creating “communion where division reigns” and promoting “a service of mercy.”

Among Santo’s first assignments: teaching religion at the order’s now-shuttered St. Philip High School on the West Side and serving as a faculty leader of the school’s glee club, according to yearbooks.

The Archdiocese of Chicago — headed by Cardinal Blase Cupich and covering Cook and Lake counties — has long maintained a public list of abusive diocesan clergy, which means those who reported to Cupich or his predecessor bishops.

After news reports and under behind-the-scenes pressure, Cupich expanded the list in 2022 to include abusive members of religious orders who lived, served or abused in his jurisdiction.

Most Chicago-area Catholic high schools are run by religious orders, which typically span geographic boundaries and follow in the mold of a particular saint or have a specialized mission. They don’t answer directly to Cupich but need the cardinal’s permission to operate in his territory.

Most Catholic parishes in the region are run by diocesan priests, who answer directly to the local bishop.

Santo not on Chicago list

Cupich’s office has portrayed the Chicago list as thorough. It includes two Servite priests among more than 160 clergy members believed to have committed sexual abuse. Santo isn’t on the list. Neither Cupich nor his aides will say why.

Servite leaders won’t talk about him, either. The order’s American province is based in a complex that includes the old St. Philip and Our Lady of Sorrows Basilica at 3121 W. Jackson Blvd.

The Carmelites, Dominicans and Jesuits are among Catholic orders operating in and around Chicago that maintain public lists. As with the Servites, though, other orders have declined to make public any listing of clergy members deemed to have abused. Those include the Augustinians, Passionists and certain Benedictines, the Sun-Times has reported.

A church watchdog group has identified as many as 11 Servites believed to have molested children.

The Rev. Eugene Smith, who oversees the order in the United States, didn’t respond to calls seeking comment. Nor did officials at the group’s international headquarters in Rome respond to questions.

The Rev. John Fontana, Smith’s predecessor, communicated with the Diocese of Springfield-Cape Girardeau, Missouri, in 2018 or 2019, when that diocese was compiling its first list. A new chapter in the sex abuse scandal had just emerged, fueled by disclosures of sex abuse and cover-ups in Pennsylvania. And church organizations around the country were taking steps to embrace greater transparency to appease members expressing outrage.

Church officials in Springfield-Cape Girardeau contacted religious orders to ask about any abusive members. The Servites flagged them about Santo, who had been associate pastor of Ste. Marie du Lac, a parish in Ironton, Missouri, from 1964 to 1966.

“The diocese did an internal audit of all clergy files in 2018-2019,” Springfield-Cape Girardeau diocese spokeswoman Leslie Anne Eidson says. “As part of that review, we reached out to all religious congregations around the country in 2019 in order to confirm those religious order priests that we had record of ever having served here, their dates of service and whether or not an allegation had ever been made against said religious order priests. At that time, we spoke with Father John Fontana.

“I have no information as to the who, what, where, when,” Eidson says. “I’m hopeful the Servites can and will assist.”

Fontana — now serving at Assumption Catholic Church, which is staffed by the Servites and at 323 W. Illinois St. in the North Loop — didn’t return calls and emails seeking comment.

Missouri diocese names Santo

Officials with the Missouri diocese did something other dioceses often do not. They contacted religious orders that had served in their territory and asked about sexual offenders among their clergy members. Other dioceses say they often wait for a religious order to tell them about their abusive members. If that doesn’t happen, offenders might not appear on such a list.

The pope hasn’t explained why he hasn’t ordered church authorities in the United States to establish public lists and adhere to a single standard in naming abusive clergy. A bishop interviewed by the Sun-Times, who asked not to be named, says doing so might be viewed as an unwanted precedent for the church elsewhere in the world and could lead to questions about “how much money was spent” dealing with the scandal.

In recent years, the Chicago archdiocese owed more than $200 million as a result of accusations of clergy sex abuse, in payouts and other costs, the Sun-Times has reported. Since then, Cupich has closed numerous parishes and schools, largely because of strained church finances.

Santo’s involvement in social justice

Between 1966 and 1974, Santo led St. Dominic Parish, which was at 357 W. Locust St., not far from Cabrini-Green, but has since been demolished. He was involved in social justice efforts and street ministry in the Civil Rights Movement era, according to news reports.

In 1971, the Sun-Times reported: “Working with priests from three neighboring parishes, he is drawing up a proposal for an anti-drug program.”

The story quoted the activist-nun Margaret Traxler, who marched with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma, Alabama, as saying Santo was “obsessed” with ministering to addicts: “He has visited the young victims in the national drug center in Lexington, Ky. He has put them up in the rectory. He has stayed up overnight with addicts in the middle of a crisis.”

Santo was quoted as saying Chicago needed a residential drug treatment center and suggested that the cardinal’s mansion at 1555 N. State Pkwy. — then occupied by Cardinal John Cody, who wasn’t well-liked by many in the clergy — “would be ideal for this purpose.”

Santo also created an alternative school at St. Dominic’s for troubled kids, according to news accounts, and allowed the Black Panther Party to sponsor a breakfast program on-site, calling the organizers “the most conscientious people we have when it comes to the use of the building. Their whole stress on human dignity is real here.”

Santo cited a dire need for “sensitive men and women” to “come and stay” in inner-city Black communities.

By 1974, Santo had moved on to the Diocese of Lansing, Michigan, where he became a chaplain at a federal prison.

“The only information the diocese of Lansing has on record relating to the late Mark Santo is a paper file dating back to the mid ‘70s which states that the Rev. Mark Santo . . . served as a chaplain at Milan Federal Prison on June 23, 1974,” says David Kerr, a spokesman for the Lansing diocese.

Santo isn’t on the Diocese of Lansing’s list of abusive clergy, which largely includes only the names of clergy members deemed to be credibly accused of child sex abuse in that jurisdiction or who live there now.

“We have no allegations of abuse relating to Father Santo’s time within the Diocese of Lansing,” Kerr says.

Between 1976 and 1979, Santo was pastor of Detroit’s St. John Berchmans Parish, which had a high school run by the Servites.

Santo isn’t on the Detroit archdiocese list, which includes diocesan clergy and religious order clerics who served in southeast Michigan and were credibly accused of abuse “either locally or in another area.”

“We have no record of complaints or allegations against Mark Santo,” Detroit archdiocese spokesman Ned McGrath says. “The Servite site does not list priests with credible accusations and / or their assignments. I’m the guy in Detroit who adds religious order priests to our website. But I only can do that if the religious order notifies us. To my memory and in checking my records, I have never heard anything from the Servites.

“So, starting this coming week, I will do my due diligence with the Springfield-Cape Girardeau diocese. I suspect it will result with a listing of Mark Santo on our web page.”

Around 1980, Santo ended up working in the Archdiocese of Miami, according to church officials and news accounts, though church records for part of this period are inconsistent.

“During this time, his assignments included chaplain at St. Francis Hospital,” which no longer exists, “and director of prison ministry, until he left in 1991,” Miami archdiocese spokeswoman Mary Ross Agosta says.

A Miami Herald story in 1988 quoted Santo, who was chaplain at a federal prison in the area, as complaining that the state’s prison system favored Protestant chaplains to the detriment of inmates: “I think subtle pressure prevents Catholics from fully practicing their faith.”

That year, he left the Servites but not the priesthood, according to his death notice.

At Miami archdiocese, no public list of credibly accused clergy

The Archdiocese of Miami is one of three U.S. archdioceses without a public list of abusive priests along with the Archdiocese of San Francisco and the Archdiocese for the Military Services.

Sex abuse victims and church reformers have long pushed for church organizations to create public lists to help hold the church accountable, acknowledge sins and crimes of the past and help promote healing.

Then-Bishop Andrew Bellisario, now an archbishop, wrote when his Diocese of Juneau, Alaska, released a list of credibly accused priests in 2020: “The truth is essential if there is ever to be healing for victim-survivors and our Church.”

St. Louis Archbishop Robert J. Carlson wrote in 2019, when his archdiocese released a list: “Publishing these names will not change the past. Nothing will. But it is an important step in the long process of healing. And we are committed to that healing.”

A patchwork of lists

But others haven’t joined them. As a result, there’s a patchwork of lists. Some include nothing more than names. Others also have assignment histories showing where clergy members served. Some include an assortment of other details, such as when abuses occurred and were reported.

There also are varying standards of who should be included on such lists, such as not including the names of clergy members against whom accusations were made only after they had died.

In Miami, Agosta says: “The archdiocese reports every allegation to the appropriate state attorney’s offices. It’s all public record, and any priest with credible allegations is placed on administrative leave, and his parish/entity parishioners/constitutes are informed.”

As in Miami, a number of smaller American Catholic dioceses — including the Diocese of Honolulu and the Diocese of Portland, Maine — have no lists.

The Diocese of Worcester, Massachusetts, lists the number of offenders who served there but not their names.

“There is no other precedent for the publishing of lists of the accused in society — even of those accused in other positions of trust, such as medicine, education or law enforcement,” Bishop Thomas McManus says on the Massachusetts diocese’s website. “Such lists can be a cause for deep division among many members of our church, who see this as publicly branding as guilty those who never have been charged by law enforcement or had a chance to defend themselves in a court of law, given the fact that many decades have passed between the alleged abuse and the reporting of that abuse or because they were already deceased when the allegation was first received.”

The Diocese of Orlando lists only names, without details such as assignment histories or the number of accusers. The Sun-Times found that one man listed in Orlando is a former high-ranking priest there who now lives in Chicago — and isn’t on Cupich’s list.

Santo not on Rochester, Minn., list

The Diocese of Winona-Rochester, Minnesota, has a list, but Santo isn’t on it despite serving there in different capacities. In 1991, he started work as a prison chaplain in Rochester.

![St. Bridget Church in [Rochester,] Minnesota, where the Rev. Mark Santo briefly served. Diocese of Winona-Rochester](https://www.bishop-accountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/c-2024-04-19-Herguth-Catholic-Priest-ph-St-Bridget-Church-Rochester-MN.jpg)

By 1993, he also was ministering at St. Bridget’s Catholic Church in Rochester — when a friend Santo had allowed to stay at the rectory was charged with possessing child pornography, according to court records and news accounts.

Four members of the parish “were in the rectory paying bills,” according to court records. “There seemed to be a problem with the furnace so they went to check the furnace and found a room that contained a large number of VCR tapes. The tapes had handwritten titles and also had strange titles. Using a VCR, the four men viewed 6 to 8 of the tapes and found that the tapes contained men engaged in different sex acts with other men, some which appeared to be minors.

“These tapes were reported to Father Santo who stated that they were ‘Carl’s’ tapes.”

A police search of the rectory discovered a magazine titled “Youngsters” with photos “depicting obvious male children in the nude,” court records show.

Santo’s house guest later pleaded guilty to misdemeanor possession of child pornography. There was no evidence Santo had viewed any illegal images.

Bishop John Vlazny, a Chicago native who’s now retired and living in the Archdiocese of Portland, Oregon, had to deal with the fallout, detailed in a Winona Daily News story that said there was a petition signed “by nearly 100 parishioners requesting Santo be removed before his term expired in May.

“The petition also questioned Vlazny’s judgement and investigation of the situation.”

Vlazny didn’t return calls seeking comment.

Santo is not on that diocese’s list because “no credible allegations were made against Father Santo during his service in our diocese,” says Peter Martin, spokesman for the current Winona-Rochester bishop, Robert Barron, who grew up in Western Springs.

“We reached out to both the Diocese of Springfield-Cape Girardeau and the Order of Servites and have received no response,” Martin says, declining to say when that was done, “but, after we have completed our internal processes and verified that Santo has been credibly accused, we will add him to our list on the website.”

Santo moves again, to Milwaukee

Within a few months of his friend’s pornography arrest, Santo had moved on to the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, which “incardinated” him, essentially making him one of its diocesan priests.

But a Milwaukee church spokeswoman, Sandra Peterson, says “he never served in any role on behalf of the archdiocese and only lived in the area for a year or so.”

Church officials won’t explain that or say why Santo isn’t on the Milwaukee archdiocese list of credibly accused clergy.

Led by Archbishop Jerome Listecki, a Chicago native from the Southeast Side, Milwaukee is one of eight archdioceses in the United States whose lists include only abusive diocesan clerics. Twenty-three archdioceses include abusive diocesan and religious order clergy, including the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

While still affiliated with Milwaukee, Santo started working as a prison chaplain in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles in the 1990s.

“Father Mark Santo was not included in the consolidated list of accused clergy in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles since the archdiocese did not receive any report of misconduct involving Father Santo,” Los Angeles archdiocese spokeswoman Doris Benavides says. “Archdiocesan records indicate that Father Santo had taken a position as a chaplain at the Los Angeles Federal Institution Metropolitan Detention Center as an extern priest of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee . . . and that in 2006 the Archdiocese of Milwaukee informed the Archdiocese Los Angeles that he left Los Angeles in 2002.”

Extern priests belong to one diocese and serve in another.

The church’s Official Catholic Directory says Santo continued to serve as a prison chaplain in Los Angeles until 2006 or 2007. There are other years in which he is not listed at all.

“Now that the Archdiocese of Los Angeles has been informed of the allegation involving Father Santo through this inquiry, his name will be included for review to be added to the upcoming update to the list of accused clergy,” Benavides says.

Santo’s death notice, provided by the Milwaukee archdiocese, says he retired in 2002 and later moved to Toronto, where the church says there are no records to indicate he ministered and where there is no public list of child-molesting clergy.

In 2002, the Boston Globe published a series of stories about child sex abuse by priests and cover-ups by bishops. A series of church reforms followed — including the creation of some of the first public lists of priest offenders in Tucson and Baltimore and pledges that clerics with even a single credible accusation of abuse would be forever barred from public ministry.

It’s unclear when the abuse that Santo was accused of is said to have happened and when church officials became aware of any accusations.

Around 2004, though, church leaders alerted ecclesiastical jurisdictions around the country not to allow Santo to engage in public ministry because, according to a person who has seen the paperwork, they “didn’t know where he was.”