HARRISBURG (PA)

Washington Post

October 5, 2023

By Petula Dvorak

As more states ease path for civil justice, institutions that harbored attackers deploy tactics to limit liability and silence survivors

He knew “luck” wasn’t the right word the moment he said it.

But Nicholas Finio was trying to describe the way everything lined up perfectly for the reckoning he’d spent decades working toward.

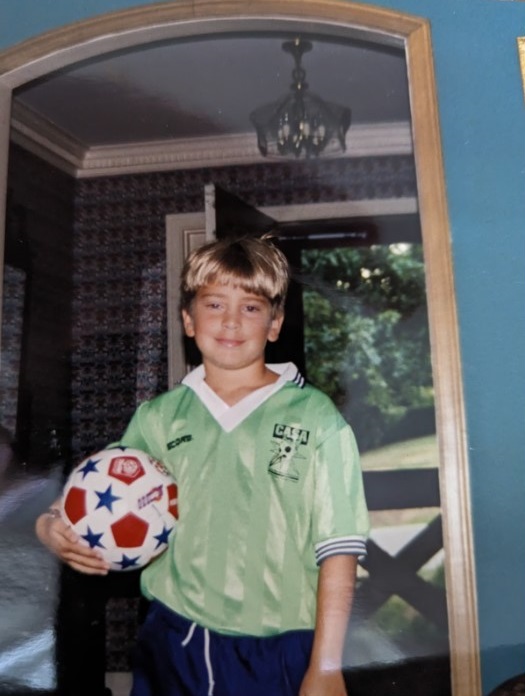

He filed a lawsuit in time, he worked with an experienced legal team and a good therapist. He was ready to confront the defrocked priest whose persistent sexual abuse had turned his years as a blond-haired altar boy delighted to be chosen for the solemn duties at Mass into a nightmare. The terror of the abuse lived inside him for 15 years, it followed him through high school and college, into his relationships and his marriage. It even made him think about suicide.

“It was the hardest thing I ever did in my life; it was terrifying,” said Finio, now 34 and an assistant research professor in the School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation at the University of Maryland. “The first time I ever told a lawyer about it I was dripping with sweat and my hands were shaking.”

And then?

Silence.

The Pennsylvania Archdiocese where Finio had been an altar boy reached for a shrewd and now-familiar playbook the Catholic Church has been deploying to muzzle survivors: declaring bankruptcy.

That meant the case that Finio had filed in 2018, when he was within the statute of limitations, that had been building for two years of discovery and paperwork, was folded into a bankruptcy hearing.

“The one piece of power I still had — the ability to speak to the public, in the courtroom — was taken away from me,” Finio wrote to me this week. “I did not have that ability as an abused child, and they took it away from me again as an adult survivor.

“The church, with its immense power, cash assets to pay lawyers, and actuarial science,” Finio wrote, “chose to relegate my story and those of dozens of other survivors to [E]xcel spreadsheets, paragraphs in emails, and [W]ord documents.”

It was as if “they had the cheat code,” he said.

And that’s exactly what the Archdiocese of Baltimore did, filing for bankruptcy Sept. 29 — two days before Maryland’s Child Victims Act became state law. The law was intended to open the door for hundreds of survivors to sue the church for its part in thousands of horrific sexual acts committed against children, and for church leaders’ complicity in enabling priests and covering up the abuse.

He is speaking out now because other people are about to endure the “enraging” process that he went through.

“The bankruptcy judge didn’t talk to us,” he said. “There’s no getting interviewed by anybody — you’re just telling your story to the insurance companies and everybody sits around the table for a couple of years.”

Finio was part of the small committee of survivors who work with bankruptcy lawyers in these cases. They are seen by the court as “creditors.” More than two dozen U.S. dioceses have deployed the same tactic, according to the Catholic News Agency. They call it a “restructuring” and say — from their gilded and historic buildings — that the move is crucial to their survival.

“I had to deal with a lot of anger in the last three years,” he said. “Not really having any recourse, any ability to act on everything that has held me back for so long.”

Survivors, the lawyers who deal with these cases said, aren’t in it for the money. They want to be heard. They want the rest of the world to understand the adults’ complicity, the calculated coverups that kept them tortured for years.

“Survivors don’t want to get processed,” said Benjamin Andreozzi, who was Finio’s lawyer, has represented victims in New York and New Jersey and who is now representing about 20 survivors of abuse in the Archdiocese of Baltimore.

When Finio saw all of this playing out in Baltimore last week, he decided to speak publicly for the first time, forgoing the John Doe anonymity of his lawsuit. He wants the church, the priest and other survivors to hear his voice.

The priest who Finio says abused him, John G. Allen, 79, is living in an apartment in Harrisburg, according to public records. He did not respond to my email seeking information. His only public comment on record about the allegations against him was a guilty plea in 2020 to two counts each of indecent assault against a child under 13, indecent assault of a child under 16 and corruption of minors— all crimes involving altar boys, according to media reports.

The Dauphin County Court judge gave him five years of probation and life on the sex offender registry, where he submits his photos, address and a description of his tattoos (a Chinese Capricorn, a moon, a star and a four-leaf clover, all on his left thigh.) He submitted his most recent photo to the registry in August.

Ordained in 1970, Allen has a long history of sexual assaults and incidents, according to the grand jury report by the Pennsylvania attorney general.

Each time something happened, the church knew.

The grand jury report documents how the church knew Allen was arrested for soliciting an undercover police officer. They heard from boys who said he paid them for sex acts. Strip poker. Nights in a hotel. Backroom invitations before services. And a bishop got the memo about Allen’s alleged confession — at a Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous meeting — that he was obsessed with young boys, the report states.

And through all that, Allen was moved around nine parishes across central Pennsylvania.

It was in 1999 that Finio was a 10-year-old altar boy at St. Margaret Mary Alacoque parish in Penbrook, dreading every time Allen was the priest celebrating Mass.

Finio said the priest groped and molested him dozens of times over the three years he served at the altar. He told no one at the time.

When Finio sued in 2018, the church offered a small settlement. He wanted a trial.

Then, the bankruptcy shut it down.

He wants the Baltimore survivors to know they are not alone, and that although they’re in for a long and frustrating process, they should persevere.

“Don’t stop fighting,” he tells them. For other survivors. For today’s children. For themselves.

Alice Crites contributed to this report.