PORTLAND (ME)

Boston Globe

January 2, 2023

By Mike Damiano

The Diocese of Portland argues the amendment is unconstitutional.

A change in Maine law has unleashed a flood of new allegations of long-ago sex abuse by priests. But now the Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland is challenging the legislation in court in an apparent attempt to stem the flow of lawsuits.

The Childhood Sexual Abuse amendment, which was signed into law last summer, retroactively eliminated the statute of limitations for lawsuits alleging childhood sex abuse in most circumstances. The result is that former altar boys and Catholic school students who are now in their 50s, 60s, and 70s can sue the church over abuse that allegedly occurred half a century ago or even earlier.

The elimination of the statute of limitations was a salve for people like Robert Dupuis, 73, who said he was abused by a priest when he was 12 years old and had never been able to confront the church as an adult. In June, he filed suit against the Roman Catholic Diocese of Portland.

Dupuis is far from alone.

His lawyer, Michael Bigos, head of the sex abuse practice at Berman & Simmons in Lewiston, said his firm is representing “approximately 100″ clients who are nowable to bring claims against the Catholic Church and other defendants. More than half of those clients, Bigos said, allege abuse by Catholic Church personnel, including priests.

Boston attorneyMitchell Garabedian, the longtime advocate for clergy sex abuse victims, said he represents about 20 clients whose claims against the Catholic Church in Maine are possible because ofthe amendment.

The Diocese of Portland isattempting to head off the lawsuits by challenging the amendment itself. In November, the diocese’slawyers argued in court filings that the amendment was unconstitutional under Maine law because it retroactively eliminated statutes of limitations that had already expired. If the challenge succeeds, lawsuits made possible by the amendment would have to be dismissed.

Lawyers representing Dupuis and other plaintiffs say theyintend to rebut the diocese’s argument in court in January.

The diocese did not respond to multiple requests for comment last week.

Dmitry Bam, vice dean and provost at the University of Maine School of Law, said that existing Maine precedents seemed to favor the church’s position, but that the question has not been definitively settled.

The legal dispute is expected to reach the Maine Supreme Court, which could decide the case this year. Until then, dozens of claims will remain in limbo.

The effort to pass the amendment was set in motion after state Representative Lori Gramlich heard a radio segment about a similar move in New York. “That resonated with me because I am a survivor of child sex abuse,” she said.

Like many survivors, she had reached middle age without coming forward about the abuse inflicted on her by her late stepfather, she said. “We know that the average age for survivors to come forward is 52,” she said, citing a 2014 study by German researchers.

In 2000, the Maine Legislature passed a law that indefinitely extended the statute of limitations for most civil claims about child sex abuse alleged to have occurred since 1987. But that law couldn’t help people with older claims, whose statutes of limitations had already expired.

Last year Gramlich introduced a bill that would retroactively eliminate the statute of limitations for all cases of child sex abuse. Now even people in their 80s who had been abused in the 1950s could bring claims.

Since September 2021, when the law went into effect, oldersurvivors have come forward with claims against a wide range of defendants, including summer camps, a state prosecutor, and the Boy Scouts of America. Many have said in news conferences and interviews that what they want, more than a cash settlement, is belated accountability for the people and institutions they say harmed them. (The amendment includes some exceptions for government agencies.)

“My motivation for putting [this amendment] in was not about lawsuits,” Gramlich said. “It was about justice.”

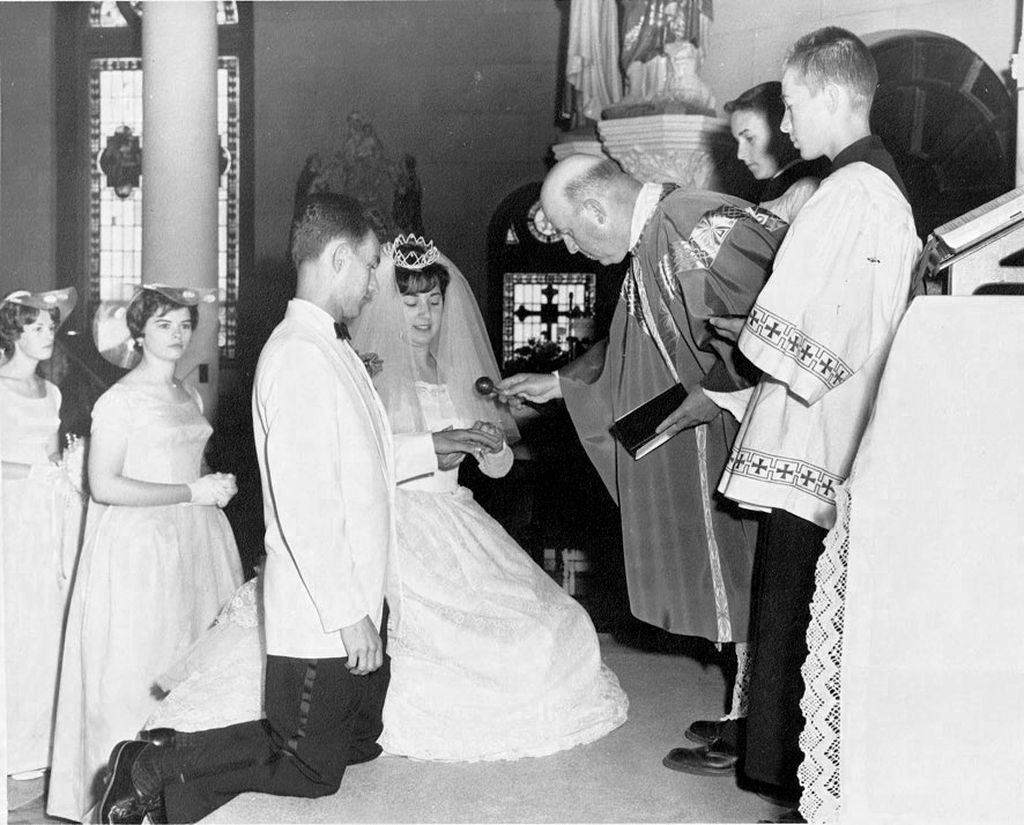

Dupuis was 12 years old when he started doing odd jobs for the Rev. John J. Curran at St. Joseph Church in Old Town. It was natural for Dupuis to seek work there, he said, because for his French-speaking family living in a small central Maine community, “the church was everything.”

In the fall of 1961, Curran periodically instructed Dupuis to join him in a large closet where Curran had placed a chair, according to the lawsuit filed by Dupuis. (Curran called the closet his office, the suit said.) There, Curran allegedly pulled Dupuis’s buttocks against his crotch and touched Dupuis’s genitals over clothing. After the abuse, the priest would pay Dupuis his wages, the lawsuit said.

Eventually, Curran dismissed Dupuis from the church job and told Dupuis’s peers he was “unreliable,” the lawsuit said. At least two other men have said Curran, who died in 1976, sexually abused them when they were children, according to news reports and investigative records released by the Maine attorney general.

The abuse, which Dupuis would keep secret for nearly 50 years, wreaked havoc on his life, he said in an interview. It may have contributed to his alcoholism and it left him with crippling trust issues, he said.

“I never really had any friendships,” Dupuis said. “Even my wife and I never became friends until I went to recovery.”

In 2006, when he was 57, he began a recovery from alcoholism and told family members about the alleged abuse, he said. The next year, Dupuis spoke out publicly as part of a successful push to remove Curran’s name from an Augusta bridge that had been dedicated to him.

But any potential claim against the Catholic Church had long since expired due to the statute of limitations. After last year’s amendment made a lawsuit possible, Dupuis was motivated to come forward because he felt the church had never “come clean” about the long history of clergy sex abuse.

“They continue to sweep all the issues under the rug,” he said. “They keep minimizing what happened to me and so many other people.”

The Maine amendment that made Dupuis’s lawsuit possible followed similar, but often more restrictive legislation, in other states.

In 2014, Massachusetts passed a law that retroactively extended statutes of limitations for lawsuits over child sex abuse. But accusers generally have to be 52 years old or younger to sue alleged abusers. To sue institutions, they must have discovered within the previous seven years that the alleged abuse harmed them, such as by leading to alcoholism or post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Massachusetts needs to abolish statutes of limitations concerning sexual abuse claims across the board,” said Garabedian, the attorney for many of the victims in the priest sex abuse scandal exposed by the Globe’s2002 Spotlight investigation.

The Catholic Church has challenged statute of limitations reforms elsewhere. In 2015, the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled against the Hartford Diocese, finding that a retroactive change to statutes of limitations was permissible under the state constitution. The same decision noted that Maine law seemed to prohibit retroactive changes to statutes of limitations.

Gramlich, the Maine legislator, said she wasn’t surprised that the church would challenge her amendment.

“It caused a lot of angst with institutions,” she said. “I think the people who have come forward in the last year are just the tip of the iceberg.”

Mike Damiano can be reached at mike.damiano@globe.com.

Show 51 comments