OAKLAND (CA)

San Francisco Chronicle [San Francisco CA]

July 19, 2022

By Rachel Swan

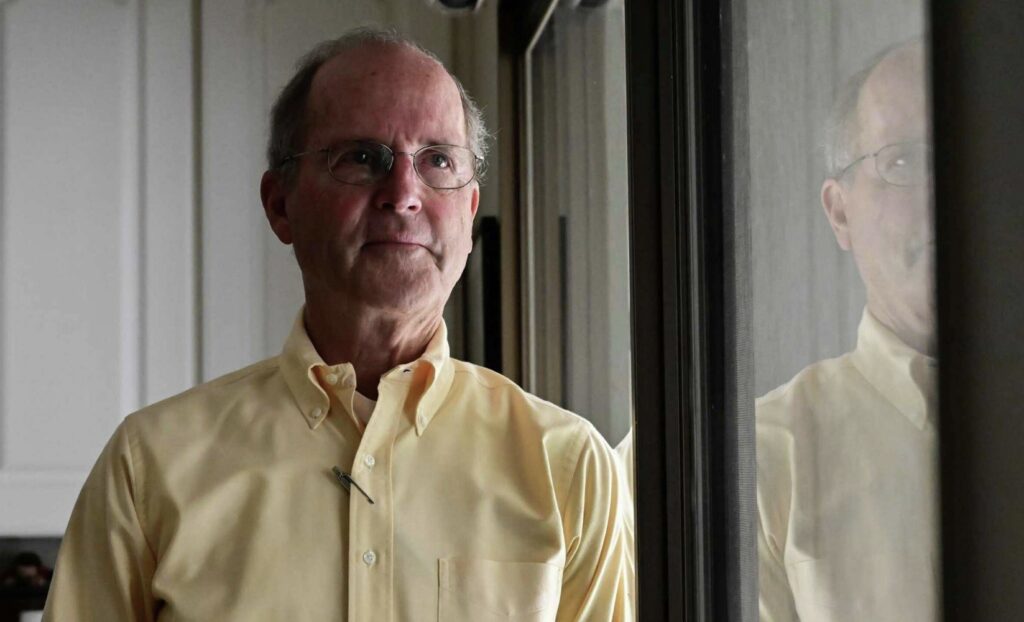

He spent 17 years as a priest in exile, railing against what he said were the misdeeds and cover-ups of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Oakland, until the Vatican finally cut him loose in March.

Months later, Tim Stier delivered his final salvo: a scorching “farewell letter” that condemned several bishops, criticized the Catholic clergy for retrograde attitudes toward gender equity and LGBTQ civil rights, and cited specific allegations of sexual abuse that Stier says the church ignored or tried to conceal.

His missive became a new flare-up for an institution grappling with public controversies over abortion and civil rights, and with the fallout from a painful history of abuse that has jolted parishes throughout the country.

“Dear No-Longer-Fellow Priests,” it began, “this will likely be my farewell letter to most of you, which may be glad tidings to those of you who did not enjoy hearing from me.”

In recent interviews with The Chronicle, Stier reflected on the blistering critique he wrote and distributed widely, an apogee to nearly two decades of protest, penned four months after his defrocking on March 19.

The ousted priest counts himself among a small community of early whistleblowers who have tried to persuade Catholic clergy to atone for past wrongs and to pull the church into modern times.

“If you speak out on these issues, you’re going to be crushed,” Stier said.

A spokesperson for the Oakland diocese did not respond to specific allegations in Stier’s letter, but sent a statement to The Chronicle about his ouster.

“We wish Mr. Stier all the best in this new chapter in his life,” the statement read. “The process by which the pope removes a man from the clerical state, which you reference as the ‘defrocking process,’ is extensive and thorough. Therefore, it can take considerable time.

“You’ll need to ask Mr. Stier why he made the decision to abandon his priestly vows and ministry many years ago.”

Tension between church leaders who wish to preserve rigid doctrine and parishioners who want a more open dialogue has been playing out in the largely liberal Bay Area. San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone, who previously served as bishop in Oakland, recently denied communion to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a San Francisco Democrat, saying she must renounce her support of abortion rights.

Pelosi later received communion from Pope Francis during a trip to the Vatican last month.

By standing up against the system, Stier speaks for a majority of Catholics who support LGBTQ rights and the ordination of women and denounce sexual abuse, said Marianne Duddy-Burke, executive director of DignityUSA, an organization that advocates for equal treatment of all of the faithful in the Catholic church.

Most of the nation’s 433 active and retired bishops follow the official teaching that gay and lesbian relationships are “objectively disordered,” and some have passed policies against the use of pronouns that don’t reflect the gender a person was assigned at birth, Duddy-Burke said.

She views Stier as a symbol at a moment of upheaval in the Catholic church— an outlier among diocesan priests, most of whom behave as “company men,” intent on ascending the hierarchy. Yet the positions Stier represents are “very valid and well within the Catholic mainstream,” Duddy-Burke said, even if the average parishioner or clergymember does not feel empowered to express them.

Over the years, Stier said, “I would get cards and letters from priests supporting what I was doing. I invited them to come (demonstrate) on Sunday mornings, but none of them were willing to risk that.”

He said a system committed to top-down authority, mandatory celibacy and the subordination of women’s voices may have to collapse before it can evolve. The church’s resistance to change may be its undoing, he said, “either through bankruptcies” from lawsuits “or disgrace.”

Stier has cast himself as an agitator from within, sustaining his Catholic faith even as he published op-ed pieces about the alleged hypocrisy of the church, or picketed outside Oakland’s cathedral on Sundays, with signs that demanded inclusion and structural reform.

“He’s been very consistent from the beginning about what his views were,” Stier’s friend, Margery Leonard, said.

Leonard, a retired teacher, met Stier when he served as pastor of Corpus Christi, her parish in Fremont, during the 1990s. Even then, he was outspoken, she said, delivering homilies that applied scripture to contemporary issues, such as homelessness or racial diversity, and trying to engage clergy in discussions about over-eating and alcoholism among priests.

“The clergy are very efficient at giving directions, but it’s just not a democratic group,” Leonard said.

She became an ally of Stier during his two decades on the margins, after he became disillusioned with the church and refused a parish assignment from Bishop Allen Vigneron in 2005.

At the time, Stier said, he insisted that Vigneron publicly confront “three issues roiling the Church”: the sexual abuse of minors by clergy and bishops’ efforts to hide it; the refusal to ordain women and treat them equitably; and the cruel treatment of LGBTQ parishioners “based on an outdated theory of human sexuality.”

The diocese “didn’t know what to do with me,” Stier said. “They were hoping I’d come back. I was a well-respected, competent pastor.”

What began as a standoff became a protracted stalemate. From 2010 to 2021, Stier stood on the sidewalk during each Sunday mass, holding his signs and hoping that Bishop Michael Barber would emerge from the cathedral to speak with him. And during all that time, the bishop never did, he said.

He surmised that Barber was embarrassed by the public crusade, and by Stier’s demand for Barber to “hold accountable” retired Bishop John Cummins, who had ordained Stier in 1979, but who Stier later accused of abetting sexual abuse of minors by moving predatory priests from one parish to another.

Representatives of the Archdiocese of Detroit, where Vigneron now serves as archbishop, declined to comment, deferring to their counterparts in Oakland. Attorneys for Cummins did not return phone calls, and a spokesperson for the Oakland diocese declined to comment on the retired bishop’s behalf.

Stier cited several examples in his letter of priests who served during Cummins’ tenure and who the Oakland Diocese subsequently deemed “credibly accused of sexual abuse by a minor.” One of them, Stephen Kiesle, pleaded no contest to charges of lewd conduct in 1978, for allegedly tying up and molesting two boys at Our Lady of the Rosary Parish in Union City, where he was a priest and teacher.

Two years ago, one of Kiesle’s alleged victims sued him, the diocese and Cummins, claiming the retired bishop knew Kiesle was a danger to children but allowed him to work with them anyway. The suit is part of a coordinated action involving more than a hundred plaintiffs against various dioceses and other church entities, with the first case set to go to trial next year, said Kiesle’s lawyer, Mark Mittelman.

Attorneys for Cummins and Kiesle have denied all of the allegations, according to court filings.

Separately, Kiesle was arrested this year on charges of killing a pedestrian while allegedly driving drunk in a Walnut Creek retirement community. He was freed on $250,000 bail in April and the case is pending.

Stier succeeded Kiesle at Our Lady of the Rosary in 1979, the year he was ordained. At the time, parishioners informed him of Kiesle’s misconduct, he said, but he heard nothing from the pastor or the diocese.

“It was so secretive in those days,” he told The Chronicle, noting that, before 1979, he had no inkling that priests had used their position to victimize others.

In interviews, Stier pointed to two factors that motivated him to write the letter. The first, he said, was a desire for closure. Second, he wanted to leave a record “of what I learned during my 17 years of voluntary exile from active priesthood,” working with abuse survivors and other people he views as marginalized by the archdiocese.

Once he’d finished and signed the missive, he printed out copies and mailed them to 60 priests. Fifty-nine didn’t respond; one sent a short, polite acknowledgment.

This month the letter appeared on BishopAccountability.org, a website and database that tracks alleged abuse by clergy.

The nonprofit Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, or SNAP, defended and praised Stier in a statement.

“It is ironic that a priest who showed integrity has been defrocked for taking a stand for what he believes is just,” the statement read, “while priests who molested children were hidden, paid and never forced to leave the church.”

Rachel Swan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: rswan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @rachelswan