PRINCE ALBERT (CANADA)

PBS NewsHour [Arlington VA]

July 8, 2021

By John Yang

[VIDEO]

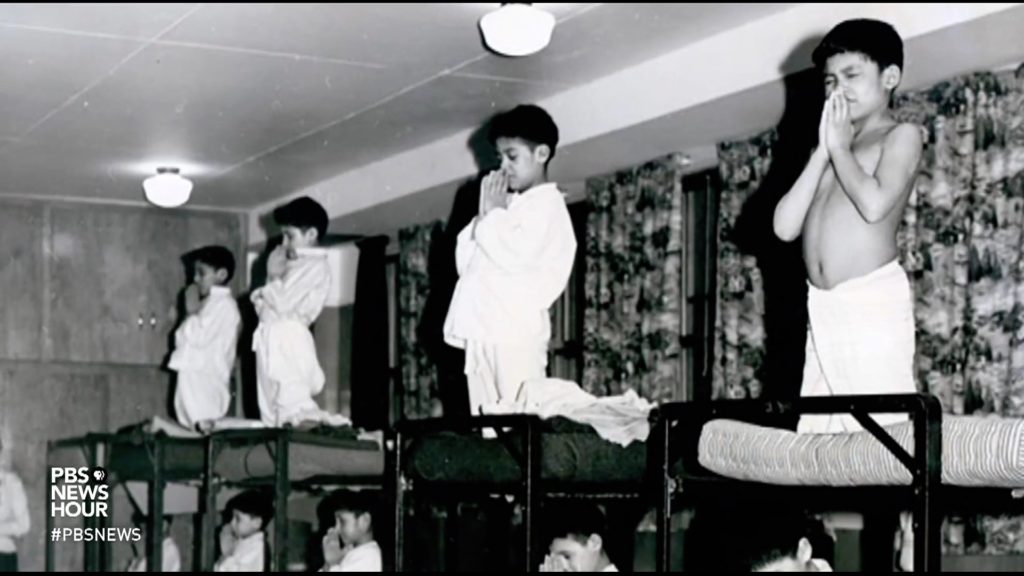

For more than a century, native children sent to Canadian Christian boarding schools were banned from speaking their languages or practicing their traditions. Hundreds died but their families were never told and bodies never returned — only found in unmarked graves recently. John Yang speaks to Heather Bear, vice chief of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, about Canada’s dark past.

Read the Full Transcript

- Judy Woodruff :The shocking discoveries of several hundred unmarked graves at former boarding schools for indigenous children in Western Canada has focused attention a dark chapter of that nation’s history.As John Yang reports, it’s a story of forced assimilation and physical, emotional and sexual abuse.

- John Yang: Judy, for more than a century, the children of Canadian native communities, including what’s known as the First Nations, were taken from their families and sent to Christian boarding schools run for the government, about 70 percent of them run by the Catholic Church.An estimated 150,000 children passed through these schools before they were closed in 1996. They were banned from speaking their languages or practicing their traditions. Children died, and their families were never told, their bodies never returned.After the discovery of these graves over the last six weeks, indigenous leaders have demanded an investigation into what they call a crime against humanity.Heather Bear is vice chief of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous First Nations, which represents 74 First Nations in Saskatchewan. She joins us from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan.Vice Chief Bear, thanks so much for being with us.I understand you went to one of these schools. What can you tell us about your experience and what it was like?

- Heather Bear: his has shaken, shaken our country, not only First Nations, but many non-First Nations, government leaders, professionals.And I think just every corner of our country has now been impacted with this new awareness that is not new. This has always been. These stories have all been told. What is coming out with this is the real story. And we need to change that legacy, because it is a very dark legacy, a dark history of First Nations, when we talk about the abuse and the horrendous crimes against children.At the time that I went was after 1972. And the chief’s task force in Saskatchewan, Indian control of Indian education, that was something that happened. So, the transition was happening, where First Nations were starting to operate these schools and the churches were transitioning out.However, there still was that lonely, heavy feeling, that you can’t really explain it. You have to be there. But also tied to that was the oral tradition, the stories, the whispers, the — what the students and teachers would talk about in terms of what had happened at those schools, and the hauntings.It was a very haunting experience, especially when you look outside your window and there is a cemetery. And I’m naming Marieval School. And I remember the swing set in the playground. Just a few steps away, you were looking at a cemetery.So, I asked the question, how many schools do you see with cemeteries in their yards? That should have been playgrounds.

- John Yang: What does this do? You talk about the legacy of this and the — I imagine, with these new discoveries in these past several weeks, it’s sort of re-traumatizing.What is the sort of impact on generations and generations of indigenous people in Canada?

- Heather Bear: You know, I could probably sit here for a hundred years and not be able to explain or talk about the impacts, because they’re so huge, and they’re at different levels.You have your survivors who are directly impacted that still live today, whether it be sexual abuse, physical, mental, spiritual, language abuse, not being able to speak your mother tongue, not being able to pray, not being — and to be told you’re not human, you’re inhuman, if you didn’t take on this Christianity.And like I say, the — what is going on right now, I think, when you look at the impacts, there’s direct impacts that are — and there’s impacts that are intergenerational. And like, today, you still have addictions. You still have family violence. You still have poverty.

- John Yang: Seventy percent of these schools were run or started by the Catholic Church. The Vatican has announced that they are going to have three of the biggest indigenous groups coming to the Vatican, going to the Vatican at the end of the year to meet with the pope.Is that enough, this sort of meeting? And what do you want to come out of that meeting?

- Heather Bear: Well, contrary to contrary to what the pope says, he believes that they — that is not their role to give an apology, according to their structure.But I believe, as a leader, as leaders, we — I think we have to take responsibility and accountability. And when we talk about healing, doesn’t the good book talk about forgiveness? And, in terms of our healing, we need to forgive. But we need that church to apologize and admit the harms that they have done, so that we, as indigenous people, as survivors of residential school, can at least turn to you and have that opportunity to forgive, and get on that long, hard journey of healing and surviving.I mean, there’s great accountability, their great leader. These were men of the cloth that abused our children. They’re men of the cloth that were perpetrators, who perpetrated the most horrendous crimes against children.I mean, I think the church owes the indigenous peoples of this country, I know for — I’m certain, with all the transgressions, they owe us something back in the name of healing.

- John Yang: Heather Bear, vice chief of Federation of Indigenous First Nations in Saskatchewan, thank you very much.

- Heather Bear: Thank you.

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/indigenous-survivor-describes-her-haunting-experience-of-boarding-school-abuse