WASHINGTON (DC)

Washington Post

May 17, 2021

By Gillian Brockell

No one from the government notified Barbara Winter about the pardon. Not the White House, not the Justice Department’s Office of the Pardon Attorney, not the prosecutor who handled her case.

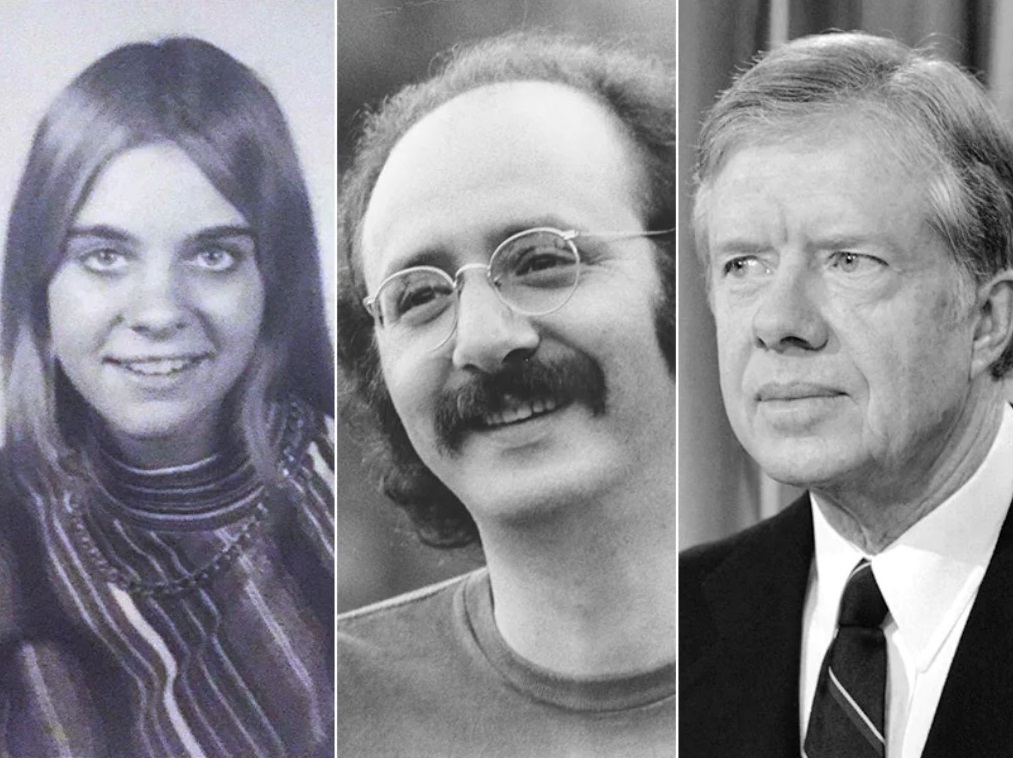

She found out from her mother, who read in the newspaper that one of the country’s most famous folk singers, who had admitted to and been convicted of molesting her when she was barely 14, had been pardoned by President Jimmy Carter on his final full day in office in 1981.

It felt, Winter says now, “like you got sucker-punched in the gut. It’s telling him, ‘It’s okay what you did, just don’t get caught next time,’ if that makes sense.”

Presidential pardons often kick up controversy, from Gerald Ford’s pardon of his disgraced predecessor Richard M. Nixon, to Bill Clinton’s clemency for fugitive financier Marc Rich, who had been on the FBI’s Most Wanted List alongside Osama bin Laden. Donald Trump, who repeatedly extended mercy to friends and political allies, pardoned or commuted the sentences of 144 people in his final hours as president, including former White House strategist Stephen K. Bannon.

But this pardon by Carter — perhaps the only one in U.S. history wiping away a conviction for a sexual offense against a child — escaped scrutiny when it happened. It was granted just hours before the American hostages in Iran were freed, which captured headlines for weeks.

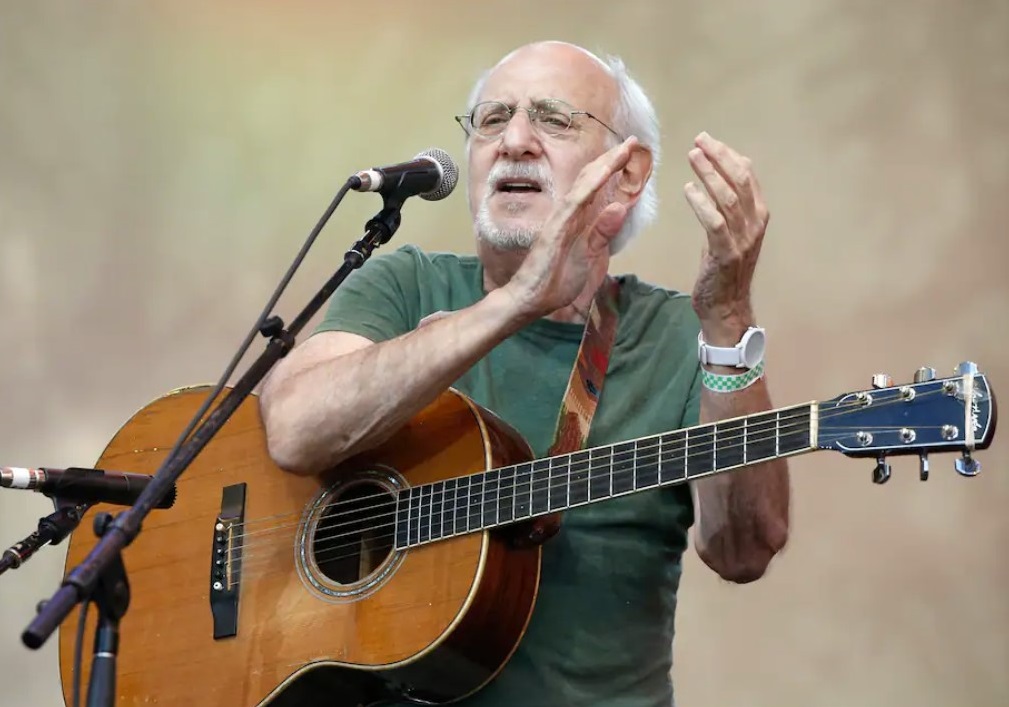

The Washington Post didn’t write about the pardon until Feb. 7, 1981. Even then, it was buried in the back of the Metro section, and only seemed notable because of who the recipient was: renowned folk singer Peter Yarrow of the group Peter, Paul and Mary, who co-wrote the beloved children’s song, “Puff the Magic Dragon.”

While Winter, now 66, has lived with the aftermath of the 1969 incident for decades, Yarrow’s crime was mostly forgotten after he served less than three months in jail.

Then, 40 years after Carter’s pardon, another woman stepped forward with an accusation of her own. In a lawsuit filed in New York on Feb. 24, 2021, she alleged that Yarrow lured her to a Manhattan hotel when she was a minor in 1969 and raped her.

Through an attorney, Yarrow, who turns 83 this month, declined to respond to questions about how he acquired his pardon or the new allegation against him.

Winter, who agreed to speak publicly about her case for the first time as long as The Post identified her by her maiden name, said learning about the lawsuit was another reminder of what she endured more than a half century ago.

“It breaks my heart to know that he was still doing it. It’s just horrible,” she said. “And I know what she’s going through. I do. And at least she had the courage to now come forward.”

‘An innocent child’

The first time Yarrow publicly apologized for assaulting Winterhe did not include her in the list of people to whom he was sorry. The day he was sentenced for taking indecent liberties with a child, he said, “I am deeply sorry. I have hurt myself deeply. I hurt my wife and the people who love me. It was the worst mistake I have ever made.”

Until then, Yarrow had been riding high professionally for a decade. Born and raised in New York City, he assembled his folk trio with Mary Travers and Noel Paul Stookey in 1961. Success came quickly. Their first album, released in 1962, sold more than 2 million copies.

“Puff the Magic Dragon,” which Yarrow wrote based on a college acquaintance’s poem, became a hit single in 1963. The politically active trio sang Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” at the 1963 March on Washington.

By the time of the incident with Winter, Yarrow was engaged to Mary Beth McCarthy, the niece of Democratic Sen. Eugene McCarthy. They’d met while both were campaigning for the senator’s 1968 presidential bid. Yarrow was 31. McCarthy was 20.

Winter, one of four kids whose parents divorced when she was 5, was not a fan of Peter, Paul and Mary. But her eldest sister was the president of Washington’s Peter Yarrow fan club. On Aug. 31, 1969, their mother dropped the girls off at church, Winter said. But instead of staying for the service, her sister, then 17, invited her to meet Yarrow, who was in the nation’s capital for a series of concerts at the Carter Barron Amphitheater. They walked several blocks to the Shoreham Hotel (now the Omni Shoreham Hotel) and called his room from the lobby. He invited them upstairs.

In the sworn statement she gave to police more than 50 years ago, the 14-year-old Winter said that when she and her sister arrived at his hotel room door, he was nude. Within minutes, she told police, Yarrow made her masturbate him until he ejaculated while her sister watched — an allegation her sister denies.

“I can’t say for sure [what happened],” Winter’s sister, Kathie Berkel, said in a phone interview, “because I wasn’t in the room … she was in the room by herself with him for five minutes, and I was right outside.”

Winter told police she resisted but did not shout or try to escape the hotel room.

“It happened when I was just an innocent child,” Winter says now. “I didn’t know anything. I was just a little girl that liked to play with her friends.”

She was terrified afterward, she said, and Yarrow told her “not to tell anybody except for, because I was a Catholic, I could tell the priest in confession.”

Winter kept the secret for six months before she confided in a friend in the spring of 1970. Soon afterward, Winter’s mother and stepfather sat her down at the dining room table and asked her what had happened with Yarrow. As she told them, her mother cried, Winter said. Then her mother called the police.

Before he was indicted by a grand jury, Yarrow pleaded guilty to taking “immoral and improper liberties” with a child, which carried a sentence of up to 10 years.

At a hearing, Yarrow contended Winter was a willing participant — a claim she denied then and continues to deny now. The judge also took issue with the claim, rereading aloud Winter’s statement that she had resisted.

At his sentencing in September 1970, Yarrow’s attorney argued “the sisters were ‘groupies’ whom he defined as young women and girls who deliberately provoke sexual relationships with music stars,” according to a United Press Internationalreport. He told the judge Yarrow had been seeing a psychiatrist since 1964 and that his condition had improved since marrying, and that after this, Yarrow’s career was clearly finished.

The judge sentenced him to one-to-three years in prison but suspended all of it save for three months. On Nov. 25, 1970, Yarrow was released three days early so he could be home in time for Thanksgiving.

Before Yarrow was sentenced, Winter’s mother had filed a $1.25 million lawsuit against him, alleging that not only had there been other incidents of abuse between Yarrow and Winter but that Yarrow had also seduced her eldest daughter into performing indecent acts over a four-year period starting when she was 14. Yarrow had encouraged her to run away from her home when she was still a minor and join him in New York, the lawsuit alleged. Berkel calls these allegations “lies.”

“He’s a very nice man, very intelligent,” said Berkel, now 69. “He had a problem. He went and got help with it. He moved on. I would love to see everyone else move on too.”

Winter confirmed her mother’s claim that while the hotel incident was the worst incident, it was not the only one. In the six-month period before she told her mother what had happened, she saw Yarrow with her sister several more times, during which Yarrow held her close to his body and placed her hand over his clothed genitals, she said.

When the press reported on the lawsuit, there were identifying details that made it clear to Winter’s classmates at school that she was the victim. Some of them felt sorry for her, she said, while others mocked her, asking, “Why didn’t you scream? Why didn’t you run away?” She began having severe pains in her abdomen, which a doctor diagnosed as a “nervous stomach,” she said, and put her on medication.

Winter said she doesn’t know how much money the lawsuit was settled for, but it was enough that the family soon relocated to New Hampshire, to a big house on a large property withhorses and a swimming pool, she said.

She saw a psychiatrist for a year “to get my feelings out,” which didn’t really work, she said. “For the most part, I try to put it in the back of my mind in a place that I don’t think about it. Because if I think about it, it just gets me upset, gets me nervous.”

More than 50 years later, she is still dealing with it.

“It just really does affect me as a person, where I’m extremely shy. And I was always so outgoing,” she said, her voice trailing off.

‘Grooming her’

The teenager had seen Peter, Paul and Mary perform throughout her childhood and had met members of the band before. “Yarrow acted in a way [the girl] perceived as paternal toward her,” her lawsuit alleged. “In fact, he was grooming her.”

The suit was filed on Feb. 24, 2021, in New York, where the state’s 2019 Child Victims Act granted a one-year window for children who’d suffered abuse to sue their alleged attackers no matter how long ago the abuse occurred. The window was later extended to two years because of the pandemic.

According to the lawsuit, the girl ran away from her home in St. Paul, Minn., in 1969 when she was still a minor. She went to New York, where Yarrow told her to meet him at a hotel. When she arrived, he brought her up to a room and raped her, the lawsuit said. The next morning, he bought her a plane ticket back to St. Paul and told her to go home.

The girl — now a woman in her 60s — suffered “severe and permanent physical and psychological injury,” the lawsuit said. She has flashbacks, anxiety and depression, difficulty sleeping and has continuing medical expenses to deal with the consequences of the assault.

The lawsuit, which sought unspecified damages, also named the band Peter, Paul and Mary as co-defendants, alleging that Travers and Stookey “knew that Yarrow liked to have sexual intercourse with and perform other sex acts on minor children.”

Travers died in 2009. “This is all a surprise to me,” Stookey told The Post. “It’s not in his character. If anything he’s over solicitous in making people comfortable.”

Court records indicate the woman reached a settlement with Yarrow and the band in April. She and her attorneys did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

‘He got away with it!’

At Yarrow’s 1970 sentencing, his lawyer claimed thefolk singer’scareer was ruined. But within two years, he and the band were singing on the campaign trail for South Dakota Sen. GeorgeMcGovern’s (D) failed presidential bid.

Throughout the 1970s, Yarrow performed at celebrity-studded events for the Equal Rights Amendment, nuclear disarmament and abolition of the death penalty. He released four solo albums and produced CBS children’s specials based on “Puff the Magic Dragon.”

In an interview promoting the cartoon, there were no questions about his conviction, but he did tell the press, “It’s a sad day when the innocence of childhood departs, and this is what Puff represents to me” — an observation eerily similar to what Winter said happened to her as a result of the assault.

Yarrow and his wife had two children before separating around 1979, according to a 2018 interview McCarthy Yarrow did with Minnesota’s West Central Tribune. They divorced in 1991.

It was concern for his children that Yarrow cited in seeking a pardon, according to the pardon application quoted by The Post in 1981. They were coming of age, he said, and he wanted to lessen “the sense of shame they will inevitably feel” by knowing “society had forgiven their father.”

The application included letters of recommendation from McGovern and former New York City Mayor John V. Lindsay (D). Both men are now dead.

Though the pardon power is one of the broadest handed to the president in the Constitution, it applies only to federal crimes, or “offences against the United States,” as Article II puts it. A president cannot pardon someone running a red light in Illinois or getting into a fistfight in Arizona because those are state crimes.

But since D.C. is not a state, the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia prosecutes crimes in the city, opening convictions up to the president’s pardon power.

Or as Yarrow told the Baltimore Jewish Times in 2006: “In Washington, it was considered a felony. In New York, it would have been a class B misdemeanor.” But if he had molested Winter anywhere else but Washington, he would not have been eligible for a pardon.

Carter, a born-again Christian and longtime Sunday school teacher, pardoned Yarrow on Jan. 19, 1981. A spokeswoman for the former president, now 96, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. The next day, Ronald Reagan was inaugurated, and scores of Americans who had been held hostage in Iran were headed back to the United States.

News of the pardon infuriated Winter’s mother, who began shouting: “He got away with it! He got away with it!” Mother and daughter always suspected Yarrow’s wife, a senator’s niece, pulled some strings to make it happen.

But in a phone interview with The Post, McCarthy Yarrow said she had no involvement in the pardon application; she and Yarrow were separated, and she was unaware he had even applied for the pardon, she said.

“But I support it,” she said, “and I’m in favor of a person like Peter deserving a pardon.” He “made a mistake” but had done many good works. “That’s what presidential pardons are and should be for,” she said.

Every year, hundreds of Americans apply for presidential pardons, which are normally handled by the Office of the Pardon Attorney in the Justice Department.

John R. Stanish, who served as the Pardon Attorney for most of Carter’s presidency, said most pardon applications took the better part of a year, or longer, to vet.

The Post reportedthat Yarrow filed the petition on Dec. 10, 1980 — meaning there would have been about five weeks between the time he filed the application and when the pardon was granted.

Stanish, who’d already left the Justice Department by then, said that surprised him. “That is about the only case that I have heard of that might have skipped the proper channels,” he said.

Patrick Apodaca, the deputy White House counsel who was then responsible for pardon applications, said that while he doesn’t specifically recall handling Yarrow’s pardon, there were a number of applications that were “accelerated” at the end of Carter’s term.

“Generally,” he said, it was “‘Let’s clean the decks’” before Reagan came to White House.

‘The worst mistake’

Over the years, Yarrow was occasionally asked about his molestation conviction. He always expressed contrition but also pointed to Carter’s pardon as evidence that he’d earned forgiveness.

“With the mean-spiritedness of our time, it gets hauled out as if it’s relevant,” he told the Baltimore Jewish Times in 2006. “You don’t get a presidential pardon if you’re not doing great work, have paid your debts to society.”

Then the #MeToo movement began. In 2019, Yarrow was set to headline a folk festival in Upstate New York when his crime was brought up.

His appearance was canceled, and he told the New York Times, “I fully support the current movements demanding equal rights for all and refusing to allow continued abuse and injury — most particularly of a sexual nature, of which I am, with great sorrow, guilty. I do not seek to minimize or excuse what I have done, and I cannot adequately express my apologies and sorrow for the pain and injury I have caused in this regard.”

While he has grown more apologetic over time, Yarrow has always discussed his crime as a singular incident: “the worst mistake I have ever made.”

Yarrow, through his attorney, declined to answer a question about whether there were other victims.

But the lawsuit filed by Winter’s mother alleged both her daughters were sexually abused by Yarrow. The 2021 lawsuit accused him of raping another teenage girl the same year he molested Winter.

And more than 50 years ago, when the Cincinnati Enquirer published a wire story about Yarrow’s 1970 sentencing, the newspaper added this at the end:

“A similar charge against Yarrow in Cincinnati was ignored about three years ago by a Hamilton County grand jury. The father of a 15-year-old girl had signed a complaint charging Yarrow took indecent liberties with his daughter when the singer appeared at the Music Hall October 27, 1967.”

‘It never goes away’

Barbara Winter lives with her second husband on a rural property at the end of a road hundreds of miles from Washington. She has an adult son and daughter from her first marriage.

She said she’s always had a difficult relationship with her eldest sister, and they are now estranged. In 2012, she learned her sister was still in contact with Yarrow and had brought her granddaughter to meet him. (Berkel said her granddaughter wanted to meet the singer and was never alone with him.)

Yarrow, Winter learned, had asked about her and how she was doing.

“And it’s none of his business. He shouldn’t be asking,” Winter said. “I want him to know nothing about my life, absolutely nothing.”

After a long career with a commercial airline, Winter is retired. She spends her days tending to her garden — tomatoes are her favorite — and caring for her dog. She far prefers animals to humans, and most of the people she knows have no idea she was abused by Yarrow. She likes it that way.

“The experience, and what you carry with you for the rest of your life — it never goes away,” she said. “Despite what people think, it doesn’t go away. You block it out because you’re forced to. You have no other choice but to block it out.”

Alice Crites contributed to this report.

Gillian Brockell is a staff writer for The Washington Post’s history blog, Retropolis. She has been at The Post since 2013 and previously worked as a video editor. Twitter