CHICAGO (IL)

Chicago Sun-Times [Chicago IL]

February 26, 2021

By Robert Herguth

A 2018 case involving St. John Stone Friary — which is near a Catholic school — caused a stir. But it wasn’t the first time a priest facing child sex-abuse allegations was moved there, once-secret records show.

Intended to be a place of contemplation, Hyde Park’s St. John Stone Friary instead became a source of consternation in 2018 when it came to light that the Rev. Richard McGrath was living there.

A former president of Providence Catholic High School in New Lenox, McGrath was accused of having child pornography on his cell phone and of sexually abusing a student and moved into the building as the allegations began to emerge.

The monastery is next to a day care center and around the corner from a Catholic elementary school. Yet no one informed the people running those institutions McGrath was living there. Not the Augustinian religious order, which occupies the friary. And not Cardinal Blase Cupich, head of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago.

People were livid when they found out.

At the time, having a priest facing child-sex allegations living at the friary was portrayed by church officials as an isolated incident. But formerly secret church records show that another alleged predator priest had moved into the same monastery in 2000, also apparently without those at nearby St. Thomas the Apostle Elementary School being told.

The transfer of the Rev. James Ray to the friary was approved by Catholic church officials, who, despite having a Catholic school around the corner, erroneously wrote that “there was no school in the immediate area,” the records show.

Ray faced multiple allegations over the years prior to moving to the friary that indicated he posed a risk to kids, though there’s no record that he committed any offense while living there. He moved in while planning to take classes at the nearby University of Chicago and left in 2002, records show.

Ray’s files were made public by the church in 2014 along with internal files on other alleged pedophile priests from the Chicago area. That was done in the face of pressure from abuse survivors and attorneys.

Ray’s paperwork shows there was coordination between different arms of the church and documents the leeway given to an accused predator.

It also shows the deference with which he was often treated by church leaders.

One of the earliest complaints about Ray, made in 1990, centered on his time at a Waukegan parish where he served from the mid-1970s into the early 1980s. Ray befriended a teenager there, and they “would engage in giving each other back rubs, then proceed lower to the buttocks and eventually mutual masturbation,” according to church records.

Then-Cardinal Joseph Bernardin was in charge of the Archdiocese of Chicago — the arm of the Roman Catholic church for Cook and Lake counties — and contending with the first wave of the still-ongoing scandal involving priests molesting children around the country and of bishops covering that up.

With the rules in Chicago relatively lax at the time, a credible allegation of sex abuse wouldn’t necessarily disqualify priests from remaining in some type of public ministry, though today the church wouldn’t allow that. In many instances during that era, priests who had abused kids would be transferred among parishes, only to offend again in their new setting.

Based on the complaint and following an administrative review, Ray was formally pulled from parish work in 1991. But he was allowed to work for the archdiocese’s Catholic Charities at hospitals under supervision, with rules that barred him from being alone with kids but still allowed a broad level of freedom, according to church records.

The year that Ray was removed from parish work, a man called the archdiocese to report having been sexually abused by Ray at the same parish in the mid-1970s, but, records show, “He did not want to follow it up any more.”

![Part of the paperwork in once-secret church files on former priest James Ray. Archdiocese of Chicago [BA-Chicago-Ray-391]](https://www.bishop-accountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/c-2021-02-26-Herguth-Church-Officials-Document-BA-Chicago-Ray-391-1024x687.jpg)

In 1993, Ray was given permission by the archdiocese to visit Medjugorje, a town in the Balkan region of Europe where the Virgin Mary was said to have appeared and that became a pilgrimage site for Catholics and other Christians. At an airport during that trip, “He met a paraplegic who asked him (Jim Ray) to masturbate him which he (Jim Ray) admittedly did,” according to church documents.

According to undated church records, several boys in the Chicago area were abused by Ray, with some of the alleged abuse involving kids as young as 10 and lasting for as long as six years.

In 1999, he was accused of touching a “boy’s genitals under his clothing,” the church records show.

More accusations have followed in recent years, including one from a Florida man who says in a pending lawsuit filed in Cook County last year that, as a boy, he was subjected to “sexual abuse, sexual torture and molestation” by Ray between 1983 and 1987. At the time, Ray was assigned to Bartlett’s St. Peter Damian Parish.

Ray, now 72, still lives in the northwest suburbs but couldn’t be reached for comment.

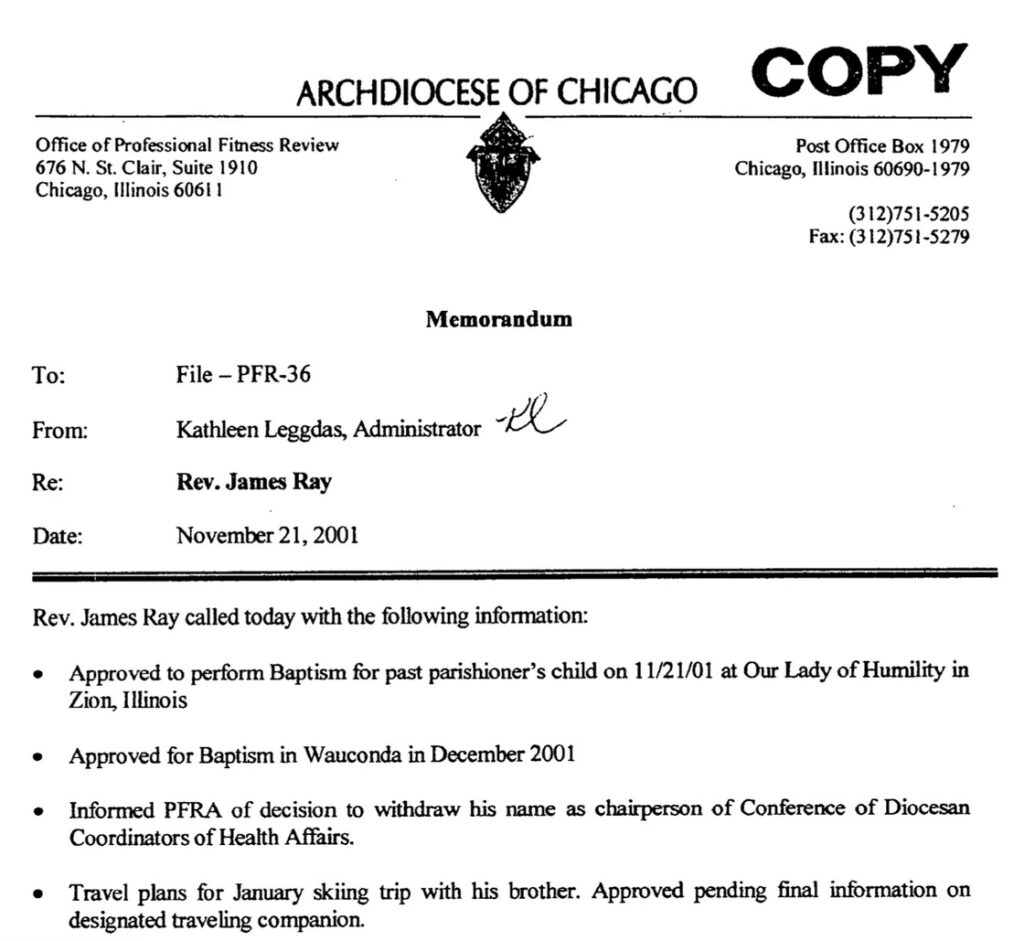

In September 2000, the archdiocese’s “professional fitness review administrator” wrote to then-Cardinal Francis George, who succeeded Bernardin, recommending Ray be allowed to move to the Augustinian friary. One of the order’s members “agreed to serve as on-site monitor” for Ray, who was subject to travel restrictions, among other rules, records show.

“There are no minors in residence and there is no school in the immediate area,” the letter said.

![A letter to the then-head of the Archdiocese of Chicago, Cardinal Francis George, from one of his advisers saying it’s fine for James Ray to move into a monastery because there’s no school nearby — though an archdiocese-run elementary school is around the corner. Archdiocese of Chicago. ]BA-Chicago-Ray-271]](https://www.bishop-accountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/c-2021-02-26-Herguth-Church-Officials-Document-BA-Chicago-Ray-271-1024x872.jpg)

A former St. Thomas school employee who asked not to be identified by name recalls no notification from the archdiocese about Ray moving to the friary and was stumped as to how the cardinal’s office didn’t know there was a school there — a Catholic school, under the archdiocese’s auspices, that takes up the better part of a block.

Within a month, Ray had moved into the four-story, red-brick monastery, according to a letter that a high-ranking archdiocesan official wrote to a high-ranking figure in the Joliet Diocese supporting Ray’s wishes to officiate a wedding in that jurisdiction, which includes DuPage and Will counties.

“Periodically Jim will request permission to celebrate a sacrament outside of our diocese and it is our procedure to notify the diocese of Jim’s past,” the letter says. “I wish to emphasize that Jim is working on his program faithfully. I strongly support his request to celebrate this wedding.”

The next day, the Joliet official wrote back granting permission.

A similar request was made by the archdiocese in 2001 for Ray to celebrate a wedding in Kansas while he was still living with the Augustinians. It was granted, with a contact at the Archdiocese of Kansas City, Kansas, writing back, “I know Jim very well from seminary days and think quite highly of him. I have no problem with Jim doing the wedding.”

Later that year, the archdiocese allowed Ray to perform a baptism in Zion and another in Wauconda, records show.

Only in 2002 — as a second wave of scandal exploded involving the greater church — did Ray move out, as church leaders adopted stricter rules for handling sex abusers.

He was sent to live on the grounds of the Catholic seminary in Mundelein at that point and removed from public ministry.

In 2009, he resigned. Three years later, Ray was laicized — stripped of his clerical status.