WALTHAM (MA)

Elle [New York NY]

February 26, 2021

By Rose Minutaglio

Anne Barrett Doyle is a devoted mother, practicing Catholic, and one of the fiercest crusaders against clergy sex abuse.

“Are you Catholic?” Anne Barrett Doyle smiled at me expectantly with kind, sea-green eyes. It was months before the pandemic hit, and Barrett Doyle had invited me over to the Boston loft she and her husband moved into after the last of their four kids left for college. A crucifix hung on the wall, and a Jesus statuette prayed from a wooden desk. Several Bibles lined the bookshelf.

We sat side by side on a plush beige couch. Barrett Doyle, small and soft-spoken, with shoulder-length auburn hair and rosy cheeks, folded her hands politely and crossed her ankles.

As co-director of Bishop Accountability, an archive documenting the sexual abuse problems of the Catholic Church, Barrett Doyle has devoted her life to chronicling the prosecution of priests who have sexually abused and assaulted children and teenagers. Barrett Doyle is one of just a handful of women fighting to expose clergy predation, both hailed as a hero by survivors and denounced as an apostate by some within the Church. She is also an ardent, unapologetic Catholic.

For some of the 1.3 billion other Catholics in the world, these last couple of decades have made her question a tough one to answer.

Am I Catholic? Let’s see: In second-grade, I was baptized in a cream-colored gown recycled from flower-girl duties at a family friend’s wedding. Mass felt special back then. We sang pretty songs, chanted important things, and wished peace upon strangers. Sitting in the pews with my parents was like an invitation to the grown-up table. I wore fancy dresses—and the shoes! Black patent-leather Mary Janes, paired with white tights. Plus a padded headband, usually red.

When it got boring, my younger brother and I thumb-warred through homilies. Afterward, we ate cheese enchiladas and drank Cokes at the Tex-Mex restaurant nearby. I never gave much thought to why I was Catholic; I just liked being a part of something that felt familial.

Now, as an adult, it’s hard to relate to a religion that mostly excludes women from power, and whose leaders have gone to great lengths to cover up heinous crimes against children. I go to Mass once a year at Christmastime, and the only part I really enjoy are the enchiladas.

So, am I Catholic? In Barrett Doyle’s living room, I settled on: “It’s complicated.”

She nodded. “Some of my closest friends are survivors [of abuse], and they would say I’m supporting a corrupt and evil hierarchy,” she told me. “I don’t attempt to defend it, and I can’t even explain it. I just know that I am a Catholic to my core. Part of my motivation is to be an agent of change in the Church.”

But the 62-year-old Boston native is more than just a force for good. She is one of the most feared and respected members of the Catholic Church; a steward of the world’s largest trove of documents holding accountable powerful men who have committed unforgivable acts—and unimaginable sin.

Barrett Doyle’s life mission began the morning of January 6, 2002. At 6 a.m., she poured herself a cup of black coffee, and tucked into the Boston Globe, savoring a peaceful moment alone before everyone woke up. She stared at the front-page feature: “Church Allowed Abuse by Priest for Years.” The story reported, in excruciating detail, how Boston Cardinal Bernard Law moved an abusive priest from parish to parish after finding out he was molesting young boys.

For years, Barrett Doyle had taken pride not only in her role as a nurturing Catholic mother, but in the ritual of walking into church each Sunday with her children trailing behind like little ducklings. But this—this news rocked her. How could she lead her family through the doors of their beloved St. Agnes Parish now?

She didn’t. Instead of going to Mass, Barrett Doyle and her husband, Bill Doyle, loaded the kids into their minivan and drove to the cardinal’s downtown offices, where protesters had started gathering with signs reading, “Speaking Out Is Holy,” “Keep the Faith, Change the Church,” and “Full Disclosure: Release the Files.”

What do you do when something you love so much goes so terribly, inconceivably wrong? When the institution that breathes life into your days—when your very belief in the Lord Jesus Christ, which for you is akin to believing in food or air—is threatened? Like a parent calling the police on her drug-addicted child, and with the clarity of a true believer, Barrett Doyle knew what to do.

She had to save the Catholic Church from itself. Barrett Doyle and her family grabbed extra signs and joined in.

Over the next two years, the unsuspecting mom, not a rallying leader by nature, went on to help organize 30 more demonstrations. It was at the home of a fellow activist that she met Terry McKiernan. He was tall and jolly, with a bushy salt-and-pepper mustache that wiggled when he talked. Like Barrett Doyle, he was both a devout Catholic and a parent. He held master’s degrees in classics and previously worked as an editor and business consultant.

They began collaborating. The protests, they realized, were good for noisy public expression, but didn’t directly facilitate action. Barrett Doyle and McKiernan came to believe the most effective ammunition was information. Documentation. Evidence. Proof.

McKiernan spent thousands of dollars of his own money to purchase court records, and together they reached out directly to survivors and their attorneys. In June 2003, Bishop Accountability was established.

“We knew that disclosure leads to more disclosure,” Barrett Doyle says. “Organizing and making the facts more accessible could then lead to [even more] disclosure.”

They taught themselves how to be researchers—collecting, organizing, and sharing hard-to-find documents. In Church hierarchy, local authority rests chiefly with bishops, who rank just below cardinals. Their name, “Bishop Accountability,” reflects their mission: to save what they love by exposing corruption from the top down.

Today the group’s massive database is unmatched, containing nearly every publicly available report on the sex abuse crisis that has dogged the Catholic Church for decades. The collection is used by researchers, survivors, and lawyers challenging the Church in court.

David Rudofski was a smiling eight-year-old boy the first time he went to confession at St. Mary Church in Mokena, Illinois. But he didn’t receive the sacrament of reconciliation. Instead, a priest committed what has come to be seen as the Catholic Church’s most defining sin.

Rudofski lived with the aching memory of being molested by a messenger of God in his house of worship for 25 years before suing the Church. But in order to make a case—and to ensure other children would not suffer—Rudofski and his lawyers needed help uncovering the priest’s dark past, one the Church had worked hard to bury. They needed documented proof.

Through the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests or SNAP, two names kept coming up: Anne Barrett Doyle and Terry McKiernan. Since Bishop Accountability was founded, the group has grown into a crusading team of five mostly self-taught investigators. Rudofski’s attorneys found enough damning evidence in ecclesiastical directories collected by Bishop Accountability to prove that pedophile priests had been systematically shuffled around for years to avoid detection. He was offered a monetary settlement, but also insisted on a currency far more precious: the release of a hidden archive with 7,000 records detailing decades of other covered-up sex abuse cases.

After it was made public, several more survivors filed lawsuits. The victory cleaved to the heart and soul of Barrett Doyle’s mission on multiple levels: Rudofski got justice, other victims gained the strength to come forward, and more documents were added to the ever-expanding pile that Barrett Doyle, McKiernan, and their staff were amassing in a back room at the Bishop Accountability world headquarters about 12 miles west of Boston in the town of Waltham.

When I visited Barrett Doyle there, it was a warm and sunny Thursday morning. She sat straight in a maroon leather captain’s chair, wearing black flats and a bright red blazer to compliment her hair. Bill and the kids smiled at me from a framed photo, the lone item on her large mahogany desk. Behind her were a series of floor-to-ceiling shelving units, and on top of those sat neat stacks of dark brown bins labeled “Priest Files: A–Z.”

Barrett Doyle grew up about a 15 minute drive from where we were sitting, the seventh of 10 children in a loud Irish Catholic family. Her mother, a homemaker and self-taught theologian, instilled in her a love and appreciation for their religion.For her, respect for the institution also included an obligation to think critically about it.

Once, when Barrett Doyle was 14, her priest gave a homily praising a decision to deny pro-choice parents their baby’s baptism. She raised her hand, stood up before the congregation, and said: “The baby did nothing wrong. This is not the parents, and the baby should be baptized.”

Barrett Doyle was accepted at 16 to Harvard University, where she attended weekly services at the historic red brick St. Paul Parish in Cambridge. She met Bill after Mass one day, and the couple got married five years later. As their family grew, faith remained central to their daily lives. Barrett Doyle planned outings to religious events and was known to step in and direct a church skit. Her favorite was a play about selflessness featuring her youngest daughter as Mother Teresa.

Back in her office, Barrett Doyle pointed at a cup of coffee and apologetically said, “Not my first today!” She’d been up since 5 a.m. drafting a response to an unprecedented decree from Pope Francis. On paper, it ordered Church leaders to report accusations of sexual abuse. But because it proposed no penalty, it amounted to a mere suggestion. Barrett Doyle shook her head. “Toothless,” she said, before taking a sip. The Catholic Church has since promulgated other efforts to tackle the crisis, including the abolishment of a “pontifical secrecy” policy that critics say protected priests from criminal punishment by secular authorities.

Barrett Doyle believes these are both steps in the right direction, but that a “zero-tolerance policy” for guilty priests and their enablers is the only way to ensure systemic change on a global scale.

She set down her mug and began listing countries where reports of alleged cover-ups have occurred: Germany, Chile, Scotland, Poland, Guam, Ireland, India, Canada.

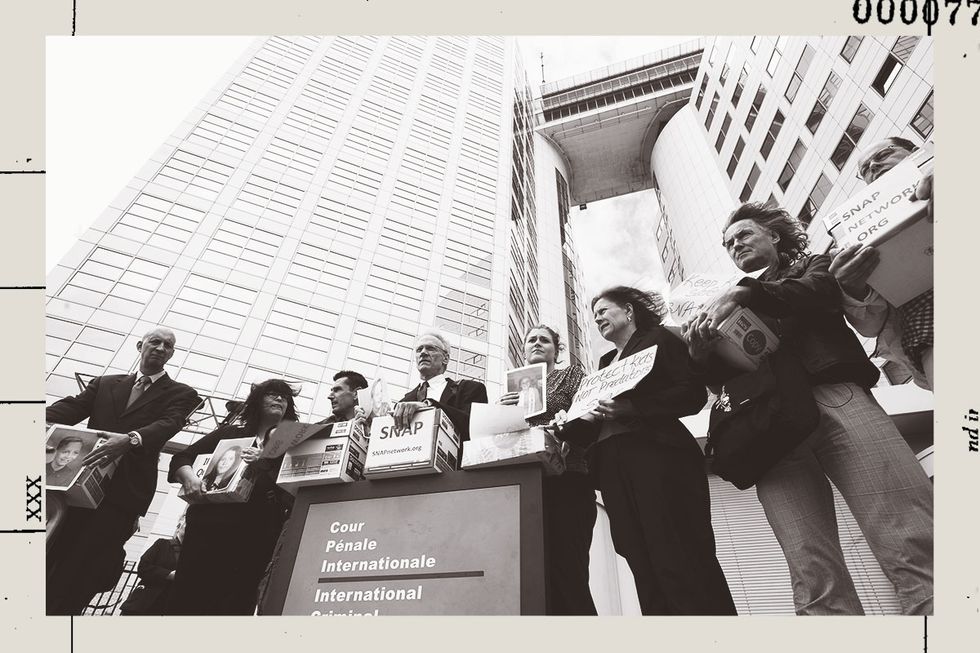

When Barrett Doyle and McKiernan first began collecting information on sex abuse, it was just in the U.S. Now Bishop Accountability includes documents from all over the world. The group’s international influence was already cemented by 2011 when survivors filed a complaint against Vatican officials with the International Criminal Court in The Hague. They arrived carrying cardboard boxes filled with 20,000 pages of supporting materials from Bishop Accountability, a stark symbol of the power of a painstakingly assembled paper trail. [Editor’s note: Vatican officials did not respond to ELLE.com’s request for comment on this story.]

Pam Spees, the Center for Constitutional Rights attorney who represented the survivors, told me that the work Bishop Accountability does is the “most important and well-respected, credible documentation of this crisis.”

Before the CDC implemented international travel restrictions due to COVID-19, Barrett Doyle flew all over the world to collect documents and meet with survivors in person. At her office, she showed me a photo of herself with a young woman in a black Nike hoodie, carrying a heart-printed backpack. They first met outside a courthouse in Argentina—the pope’s home country—where she was tracking down official records from one of the worst sex abuse cases to ever go to trial: A ring of priests and nuns accused of assaulting deaf and mute children.

The transgressions escaped detection for decades, because the abusers were purportedly moved around by the Vatican. The girl in the photo was one of several survivors who protested in Buenos Aires with signs that read, “With Our Hands and Our Voices We Break the Silence,” a reference to the sign language they used to alert the world about their abuse.

Barrett Doyle’s tone remained matter-of-fact when she told me the story, but her eyes welled with tears. “[Initially], Vatican officials tried to say this was an American problem due to our licentious lifestyle,” she said. “But as it turns out, this is just as much of a problem in conservative Catholic countries, if not more so, and it’s become manifestly clear that the Vatican engineered the cover-ups, and bishops were all complying with the playbook set out by the Vatican, which puts priests ahead of children who have been sexually abused.”

The heaviness in her office was interrupted by a knock on the door. McKiernan popped his head in to ask: “More coffee?” Barrett Doyle dabbed her cheek with a Kleenex, smiled, and said, “I’m already two cups deep.”

That day, Barrett Doyle introduced me to three other staff researchers who help track down records from courts, attorneys, and survivors desperate to tell their own histories of abuse. They largely rely on donations to carry out the work, which involves editing records to protect the privacy of survivors before adding anything to the archive. Over one million pieces of documentation are housed in rows of black filing cabinets at the Waltham office.

The drawers of tragedy are cataloged first by diocese, and then alphabetically by last name of the accused. Flip through the files and you’ll find horrifying details from each of the thousands of cases Bishop Accountability has compiled:

High on the wall above the filing cabinet hangs a row of framed black-and-white photographs. All smiling children. “Survivors we’ve worked with,” Barrett Doyle whispered before I could ask.

The disheveled depiction of attorney Mitchell Garabedian’s downtown Boston office in Spotlight is comically true to life. When I met him there, files tumbled forth and frenzied assistants ran around with stained coffee cups. In the film, Stanley Tucci plays Garabedian as an irascible lawyer hell-bent on representing survivors. In person, Garabedian’s thick Boston accent softened him, and he was generous when talking about Barrett Doyle: “For years she’s been there, quietly and consistently, working on this historical database that, in a way, is a direct juxtaposition of the Church’s position of silence.”

Garabedian uses Bishop Accountability daily to prepare his hundreds of cases. He tells me that he has two types of clients: those who see their abuser’s name in the Bishop Accountability database and come forward, and those who don’t and want documents about their abuser added.

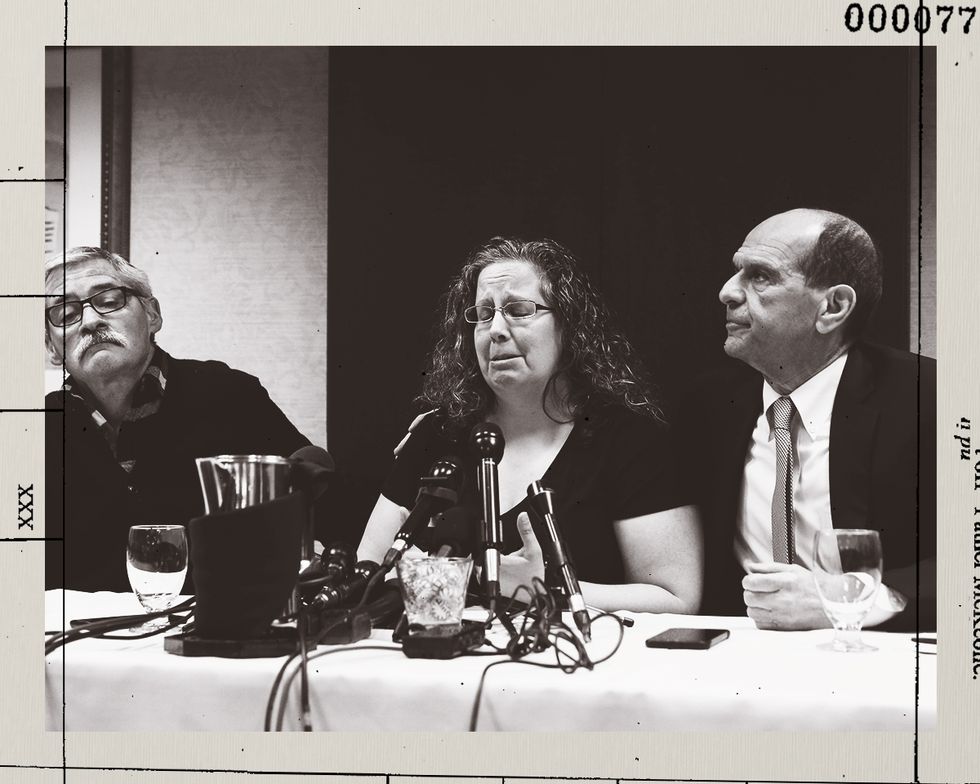

Alexa MacPherson falls somewhere in between. On a phone call, she told me how she was just three years old the first time her pastor in a Massachusetts diocese, Peter Kanchong, abused her. MacPherson said the abuse lasted for six years and only stopped when her father caught the priest as he was about to assault her on the family’s living room couch. The priest was put on probation years later. MacPherson, who suffers from anxiety and panic attacks, filed a lawsuit and was one of hundreds of survivors to publicly settle with the Archdiocese of Boston.

When she saw her attacker’s name chronicled by Bishop Accountability after settling, MacPherson, now a mother of two daughters, felt some measure of healing—and validation. “It was like, ‘Yes, now everyone can see that I was telling the truth the whole time about what happened,’ ” she says. “It’s very hard to get people who weren’t victimized and who aren’t survivors to believe you. But Anne gives credibility to our stories.”

While many survivors, like MacPherson, appreciate Barrett Doyle’s work, those who don’t approve of her unwavering faith are among her harshest opponents. Harsher, even, than the Church itself. As she fights to expose brutal crimes, Barrett Doyle is forced to consider what it means to maintain a devotion to a higher power that she was raised to trust.

In the last three years, Bishop Accountability has been inundated with accounts from survivors. Barrett Doyle believes the Catholic survivor movement planted the seeds of the #MeToo movement, which, in turn has renewed a push for transparency in the Church. Bishops are now making available an unprecedented number of lists of accused clergymen to get ahead of scandal—sometimes sending them to her directly.

“We’ve finally accepted that beloved figures can be sexual predators. Take Bill Cosby,” she says. “It stretches across other professions and industries, including churches, making it much safer for [survivors] to come forward, because they have much more reason to think they’ll be believed.”

With so many revelations, Barrett Doyle has considered expanding Bishop Accountability to include other sectors or industries, but says, “There’s no way we could take all of that on.” Her staff does, however, consult with activists from different religions, including Mennonites, Baptists, and Orthodox Jews, on starting their own databases.

For now, Bishop Accountability is focused on exposing further scandals buried inside the Catholic Church. Like so many others who now work remotely, Barrett Doyle conducts research from her Boston loft. She talks to McKiernan on the phone almost every day, and Bill brews the morning coffee.

Her focus is now on sex abuse at Indigenous parishes, both in Canada and the U.S., which she believes is severely underreported. When it becomes safe to travel again, Barrett Doyle will also visit a group of survivors in Mexico she has been virtually connecting with over the last six months. “I’m enraged on [their] behalf, I’m enraged by the arrogance of the hierarchy—but I don’t want to take down the Church,” she told me on a recent phone call. “I don’t want it destroyed. I want them to get it right. I don’t see how we get from where we are today to them finally understanding it.”

I think of my own priest back in Texas, who, to my knowledge, has not been accused of any kind of misconduct. Growing up, I made it a habit to ask him for an extra blessing after Mass. Other people hung around waiting to speak with him, but he always made time for the kids. “Bless this girl, in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit,” he would say, making the sign of the cross. In front of everyone. The attention was embarrassing, but my dad once explained that blessings are like good luck. And who among us doesn’t need a bit of extra luck?

I still don’t have an answer to Barrett Doyle’s question, “Are you Catholic?” What I do have is an unwavering faith in her mission.

The last time we met in person pre-pandemic was for (what else) coffee in New York City. She wore a simple black blouse, ballet flats, and barely there gold hoop earrings. We didn’t know it then, but the world would shut down soon and the downtown cafe where we were at would close for good.

But in that moment, Manhattan, still very much alive, swirled around her. Barrett Doyle leaned over to me, earrings twinkling in the sun. Her voice cut through the city noise: “We Catholics have a sense of everyday sacredness that each moment, no matter how ordinary, is imbued with God’s presence. I still see that holiness in the faith. It’s just part of the air I breathe, and that will always be there.”

Photos by Allie Holloway | Animation by Alina Petrichyn | Design by Mia Feitel