(AUSTRALIA)

Australian Broadcasting Corporation - ABC [Sydney, Australia]

February 17, 2025

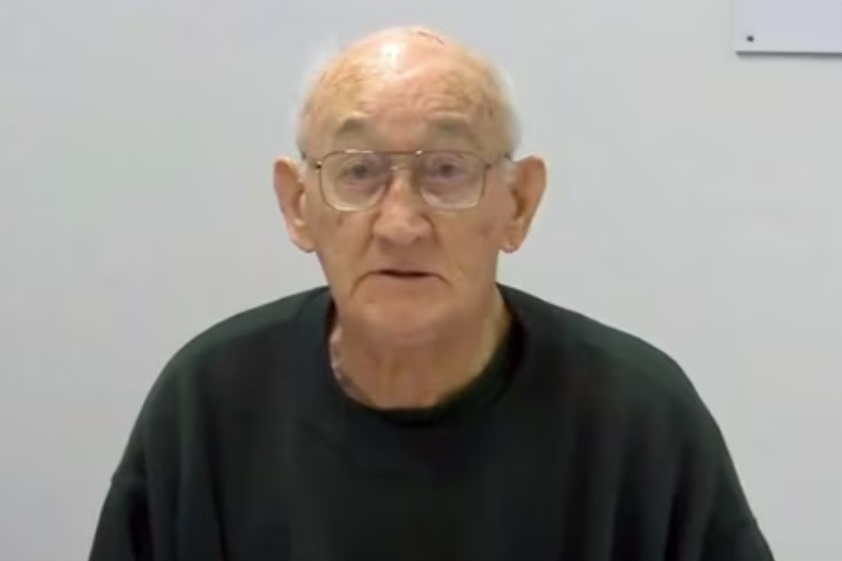

[Photo above: Stephen Blacker was nine years old when his parish priest, Gerald Ridsdale, raped him in Mortlake, in south-west Victoria. (Supplied)]

In short:

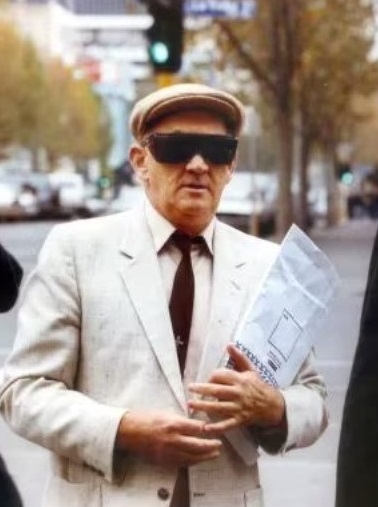

Gerald Ridsdale, who abused at least 72 children while serving as a Catholic priest, has died aged 90.

Ridsdale’s offending was central to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, and raised serious questions about the Catholic Church’s efforts to cover up the priest’s actions.

What’s next?

One survivor says Ridsdale’s death “means nothing” to him, but is urging other survivors to seek support if his death triggers more distress.

For decades Gerald Ridsdale, draped in flowing white vestments, stood before countless Catholic congregations preaching about good and evil, the innocence of children, and a merciful god.

But on him, those vestments were merely a convenient costume disguising one of the nation’s most evil men — a prolific paedophile who showed no mercy as he dashed the innocence from the lives of dozens of children.

Ridsdale, who has died in jail at the age of 90, leaves behind a dark legacy that includes the abuse of at least 72 child victims over a 30-year, unchecked reign of terror.

It is believed his appalling abuse has led to several of his victims taking their own lives, and many others enduring devastating trauma that continues to this day.

Ridsdale’s crimes changed Australia’s legal system, shaped royal commissions and inquiries, and scarred a church once considered unimpeachable.

Following the revelations of his offending, Ridsdale became emblematic of a culture of an unscrupulous church that did all it could to silence the small voices of his victims.

The life of a ‘monster’

Gerald Ridsdale was born in 1934 in the Wimmera region of Western Victoria.

At the age of 20, he entered the seminary at Corpus Christi College at Werribee, on the outskirts of Melbourne, and remained there until 1958.

During this time he is known to have sexually abused at least one boy while assisting with camps for underprivileged children.

Then, when studying in England in 1960, he abused another boy while working as a housemaster at a school.

A year later, 27-year-old Ridsdale was ordained as a Catholic priest.

Thus commenced a 30-year series of appointments followed by quiet shuffles from parish to parish, as Ridsdale caused enormous suffering to scores of children without facing the consequences.

It wasn’t until 1993 that the perverted priest was finally charged with sexual offences against multiple children, dating from the 1960s to the 1980s.

Ridsdale admitted to the offences in a Melbourne court that same year and was jailed for 12 months.

But as more victims came forward, the scale of his offending became clearer, leading to further sentences.

He was due to face court yet again this week.

He was charged eight times over the years — bringing the total number of his known victims to 72.

It makes Ridsdale not only Australia’s worst paedophile priest, but also one of the most prolific sexual abusers of children in the nation’s history.

Prior to his death, 90-year-old Ridsdale was facing yet another court case relating to the abuse of six more children.

Abuse, relocate, repeat

Ridsdale’s first appointment as assistant priest was at Ballarat North in 1962.

It wasn’t long before he was relocated following a complaint of abuse to the then bishop of Ballarat, James O’Collins, who moved Ridsdale to the parish of Mildura.

From 1961 to 1990, he was moved to 16 different parishes across Australia, many of them in regional Victoria.

Each tenure lasted an average of 1.8 years, as concerns about his behaviour would arise and the church would intervene again, relocating him to a new, unsuspecting parish, where he would abuse more children.

His behaviour was discussed at no less than 18 meetings of a diocesan body known as the College of Consulters — a group of priests chosen by a bishop.

In 1989, Ridsdale was sent by the Catholic Church “for treatment” to Villa Louis Martin in Jemez Springs, New Mexico.

The American site was dedicated to clergy members with “personal issues”. Ridsdale remained there for nine months.

Upon his return, Ridsdale promptly undertook chaplaincy work with St John of God hospitals. By late 1992 Victoria Police and the child exploitation unit began investigating his crimes.

It was only after his convictions in 1993 that the church officially defrocked Ridsdale, and removed his status as a priest.

Ridsdale’s death ‘means nothing’

Stephen Blacker was just nine years old when he was raped by Ridsdale at Mortlake, in south-west Victoria, in the early 1980s.

In giving evidence to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in 2015, Ridsdale said he “went haywire there”.

The move to Mortlake’s St Colman’s Church was Ridsdale’s 11th appointment in 20 years.

Internal church documents tendered to the royal commission suggest every boy in one class at the St Colman’s parish school, was abused by Risdale during his 1981 to 1982 tenure.

But today, Mr Blacker said the death of the 90-year-old “means nothing” to him.

“You go through a process of confronting it,” he explained.

“Either I’ve thought too much about it, or I’ve moved past it.”

In a turning point for survivors of Ridsdale’s abuse, Mr Blacker successfully sued the Catholic Diocese of Ballarat, along with two bishops, in 2018.

During the civil case, where Mr Blacker levelled negligence allegations against the Catholic Church, the diocese admitted knowledge of Ridsdale’s abuse from as far back as the 1970s.

“I learned very quickly about the hurdles in historical cases,” Mr Blacker said.

“There’s no eyewitnesses, there’s no evidence or crime scene evidence … you really are up against it.

“I took a civil case against the Ballarat Diocese, among others, and that was the first one that went through since the law change that allowed survivors of clerical abuse to go after the bigger entities.”

Mr Blacker said while there had been some progress in the way such cases were handled, it was not enough.

“The lengths that [the Church] goes to, to initially defend these cases — but really they’re just trying to run interference,” he said.

Whistleblower remembers ‘a monster’

Ann Ryan was a teacher in Mortlake from the 1970s to the 1990s, and was one of the whistleblowers who called out Ridsdale’s abuse.

She played an instrumental part in the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses into Child Sexual Abuse, and remains a staunch advocate for the rights of those who were so seriously hurt by the man she refers to as a “monster”.

“[The community] knew about it, and they did nothing,” Ms Ryan said.

“That destroyed me. Some parents went to the bishop, some went to counselling, but the community did nothing.

“You have to say that is really tragic.”

It’s been six years since the royal commission tabled its final report, which featured 100 pages detailing the extent of Ridsdale’s offending, and the culpability of the Catholic Church in his crimes.

It included admissions that multiple members of the clergy knew of Ridsdale’s abuse of children across the country, and internationally, from an early date.

Most notoriously, this included Cardinal George Pell, who was by then Australia’s highest-ranking Catholic and stationed at the Vatican.

Pell, who died in January 2023, was a former housemate of Ridsdale, but always denied direct knowledge of his abuse of children.

Today, walking through city streets in Ballarat, ribbons honouring the survivors of clergy abuse dot fences of multiple sites.

Discussions have begun between the Ballarat Diocese, survivors, and members of the Loud Fence organisation, to create a permanent memorial in the grounds of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in the city centre.

A legal system changed

Lawyer Judy Courtin represents victim-survivors and their families in civil cases, some of which remain before the courts.

While representing survivors of Ridsdale’s abuse, she was involved in a David-and-Goliath battle against the Catholic Church. In a win for those individuals and their families, the church admitted that it was legally responsible for the paedophile’s heinous crimes.

Ms Courtin was among those who fought for the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse and the Victorian Parliamentary Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Organisations.

She said those hearings had paved the way for more abuse survivors to have their day in court, but said that for some survivors, court action was a double-edged sword.

Ms Courtin said each case had the potential to bring a fresh wave of trauma to survivors and their families fighting for compensation from institutions that were supposed to protect them.

State and federal redress schemes are available to victim-survivors of abuse.

In one jury matter, $1.1 million was awarded to an abuse survivor, however the Catholic Church is appealing that decision.

In 2022, a Victorian Supreme Court ruling set a potential precedent for the future of litigation by the loved ones of those who suffered clergy abuse, with the court ruling the Catholic Church could not use a legal loophole in a lawsuit launched by the father of an alleged victim of abuse.

Ms Courtin said although civil litigation for ‘secondary victims’ was still in its infancy, she had hope for the future of Victoria’s legal system, and for those who were determined to seek justice.

Trust in Catholic Church lost, says vicar-general

In 1971, Australian census data showed 86.2 per cent of the nation identified as Christian.

In the most recent 2021 census, that number had halved to just 43.9 per cent of the population.

Globalisation and the internet have led to worldwide exposure of the failings of many Christian churches.

Vicar-General of the Ballarat Diocese Father Marcello Colasante said that in the years since Ridsdale’s arrest and the subsequent legal action stemming from his crimes, the public’s opinion of the church had understandably plummeted.

“For myself, our church doesn’t have a lot of credibility, or trust, or respect,” Father Colasante said.

“We continue to move forward in a way that is sensitive to all our people — in particular, those who are on the fringes of the church.”

Father Colasante said it would take “some generations” for the church to regain that trust.

“We have to earn people’s trust and confidence. I personally don’t take that for granted,” he said.

“We are no longer seen as ‘church triumphant’ — that era of the church is gone.”

On Ridsdale’s death, the Vicar-General kept his thoughts solely on the victim-survivors of the former priest.

Risdale has been convicted of abusing children, both girls and boys, in Ballarat East, Swan Hill, Warrnambool, Apollo Bay, Inglewood, Edenhope, and Mortlake.

“We stand in solidarity with what they are feeling, that’s where our prayers and support are — with those survivors,” Father Colasante said.

Mr Blacker said that while Ridsdale’s death meant nothing to him, he was thinking now of the other victims, and urged them to seek support.

Ridsdale’s total sentence was due to expire in September 2034. He is survived by family in the Ballarat region.