(AUSTRALIA)

The Monthly [Carlton, Victoria, Australia]

February 1, 2025

By Louise Milligan

[Photo above: James, a Pell survivor, in his first grade class photograph at St. Francis Xavier School in Ballarat in 1974.]

As the Catholic Church finds a new legal defence against child sexual abuse charges, disgust with the late cardinal George Pell’s glorification has now led some of his own victims to come forward and detail their abuse at his hand

The day politicians, priests and pundits filed into St Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney for the pontifical requiem mass venerating Cardinal George Pell as a Catholic hero, a soldier for truth, a prospective saint and an unfortunate scapegoat in a vast woke conspiracy, a mathematics teacher was at home, seething.

In David’s inbox was a letter from the National Redress Scheme that threw into serious doubt the platitudes of the faithful. It was dated December 7, 2022 – five weeks before Pell’s death.

The official letter from the government compensation scheme, set up after the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, said its decision-maker had found that in 1975, when David was eight, he was sexually abused by one George Pell at the YMCA swimming pool in Camp Street in the central Victorian goldfields town of Ballarat.

David’s fury led him to write his own reflections on the life of the late cardinal.

“What should George’s obituary be?” David wrote at the time. “I would like an acknowledgement that George was a habitual and gloating sex offender against children …

“George was charming to me. He often knew my name, and he certainly knew which family I belonged to. Sometimes he was too familiar – like in the Camp Street swimming pool …

“The debate needs balance! George’s victims still need a voice.”

Crucially, as Pell was being laid to rest in an elaborate pontifical mass on February 2, 2023, the Catholic Church, via its Ballarat diocese, had been notified of the decision to grant David compensation for his abuse by Pell.

It is not the only letter of this kind about the cardinal. In the worst example I am aware of, the scheme’s decision-makers found in August last year that a young boy, James, was anally raped by Pell in a gymnasium. That finding was made 19 months after Pell’s death. I met that boy, now a man, with his elderly mother several weeks ago in Ballarat. The effect of all of this on them both has been devastating.

The decision-maker in James’s case stated that part of the reason they accepted that Pell raped James in the gym of Ballarat’s St Francis Xavier Primary School was that there were two other complainants who also made accusations about Pell abusing them in similar circumstances.

It has to be stressed that these are not simply allegations made by David and James, they are findings of an independent body set up by the government to compensate victims.

“There are three things you can’t hide,” James’s mother, Carmel, tells me, her eyes shining as they so often do these days. “The sun, the moon and the truth. And you’ve just got to hang on to that.”

For so many men, their truth is that when they were little boys, they were abused by George Pell. The faithful at St Mary’s would have us believe, by implication, that they are all mad or confused or delusional, or part of, as Pell’s brother David told the congregation, a “woke algorithm”. That’s not my experience.

There are 14 men, three of whom have died before their time. I have met or conducted interviews in relation to 12 men who made accusations about Pell’s behaviour with boys, and a further two are on the public record, having spoken on camera to the ABC’s Revelation documentary series, which aired in 2020. Their allegations span Victoria from 1960s Phillip Island to 1970s Ballarat and Swan Hill, and 1980s Torquay to 1990s Melbourne.

I am aware of three men who make allegations about Pell’s behaviour and who have received redress payments, and at least two who have received civil settlements, as well as at least four civil cases that are currently on foot. There are six law firms who have managed these clients.

All bar one of the 14 had made contact with police, and the 14th went through an internal church-sponsored investigation presided over by a retired judge. Almost all of them had other abusers too, and the payments allocated to some of them also reflect that.

It cannot be overstated that the sadness associated with all of these men is overwhelming. Even those employed in fulfilling jobs struggle every day.

David’s wife, an academic we’ll call Jane, shares her husband’s fury at the whitewashing of Pell’s reputation by culture warriors and the church. The news of the elaborate funeral plans prompted Jane to first contact me via LinkedIn on January 30, 2023, three days before Pell was laid to rest at St Mary’s.

“In addition to the damning findings by the royal commission regarding Pell, my husband has just been offered a large payment from the [National Redress Scheme] for the abuse Pell perpetrated,” Jane wrote to me. “In light of this, and given the Catholic Church is aware of this and other awards against Pell, it is very hard to see the church provide so much pomp and ceremony around Pell’s absurd funeral.

“Catholics should act now. Those paying Catholic school fees should act now. Survivors need your positive action, not your inaction …

“Their celebration of Pell is painful.”

Though the church had been made aware of the decision-maker’s finding in David’s case in November, there was no sign it had taken the news on board when 275 priests and 75 seminarians prayed for Pell’s eternal soul the day of his funeral. Nor was there any sign of recognition of the settlements in civil cases that had also been paid, albeit with clauses stating that the church did not admit liability.

It was quite the congregation. Included among the mourners at St Mary’s were former prime ministers Tony Abbott and John Howard, Opposition Leader Peter Dutton, New South Wales upper house MLCs Mark Latham (independent) and Greg Donnelly (ALP), broadcaster Alan Jones, former vice-chancellor of the Australian Catholic University Greg Craven, and, it was said, members of the judiciary who were not named. (One wonders whether those members of the judiciary preside over child abuse cases.)

Pope Francis sent condolences through his papal nuncio. In 2020, the pontiff had tweeted after Pell was acquitted by the High Court: “Let us #PrayTogether today for all those persons who suffer due to an unjust sentence because of [sic] someone had it in for them”. In the case about which the pope was presumably implying an unjust sentence, former choirboy Witness J alleged he and another teenage boy (who never made a complaint but died of a heroin overdose when he was 30) were orally raped in the sacristy of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Melbourne in 1996. A jury accepted Witness J’s account and Pell was convicted and sent to prison. In Victoria’s Court of Appeal, the majority of the court, which had viewed the video of Witness J’s evidence as well as that of all the other witnesses, upheld the conviction. But on appeal to the High Court of Australia, the judges decided, without having viewed the videos but taking into account the evidence of the church “opportunity witnesses” who said it couldn’t have happened, that any jury acting rationally must have entertained a reasonable doubt that Pell was guilty. Pell was acquitted and set free from prison.

Hence the cries of martyrdom and witch-hunt, and analogies to the wrongful conviction of Lindy Chamberlain, which echoed through St Mary’s during Pell’s pontifical requiem mass. Chamberlain was convicted of murdering her baby Azaria but the conviction was quashed after the court reviewed flaky forensic evidence, and a coronial inquest found a dingo took the child.

Azaria Chamberlain had never been here to tell her story – she was a baby, and she was dead. Witness J was alive. And a jury and the two most senior judges in Victoria, having viewed his account, found him believable. I’ve met him and, having also spent many years meeting other victims of Pell, I do too.

The Australian’s Paul Kelly, who also attended the Pell funeral, quoted C.S. Lewis in relation to the politicians, including Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and then state premiers Dominic Perrottet and Daniel Andrews, who, in Kelly’s view, didn’t have the ticker to attend: “‘We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise’ … We live in an age of phony virtue and fabricated honour.

“Lewis was prophetic – leadership in our institutions, public and private, is administered by men without chests,” Kelly sighed.

George Pell was certainly not without a chest. His motto was “Be Not Afraid”, the congregation was reminded, as Archbishop of Sydney Anthony Fisher compared the pugilistic late cardinal to Richard the Lionheart.

“Twenty-three days ago, the lion’s roar was unexpectedly silenced,” Fisher opined of his friend, whom he said was a victim of “a media, police and political campaign to punish him, whether guilty or not”.

I cannot speak for the multiple accusers against Pell, most of whom never met each other and who were in different locations at different times. I cannot speak for Victoria Police, for the Office of Public Prosecutions, for the Victorian Court of Appeal, for the National Redress Scheme decision-makers, or for the eminent Australians who presided over the child sexual abuse royal commission for five years, read countless documents in relation to Pell’s knowledge of abusers and concluded that he did know and did nothing to stop them.

But I can speak for me, a journalist who has met so many of these men who have said Pell stole their innocence. I had no more than a passing interest in Pell prior to being asked to commence my first investigation in 2016. I had rarely given him a second thought. There is simply no reason why I would have embarked on a campaign against him. A newspaper had reported that police were investigating Pell and I was asked to look into it. At the time, knowing a lot less about child abuse than I do now, I was sceptical and wondered why these allegations hadn’t come out before.

And what I found was that there were – and, increasingly, are – compelling, tragic and well-documented claims against him. It’s been nine years since I first started on this. It has not been easy, for anyone concerned. But I can’t turn away and pretend these men don’t exist. Particularly when the church is now aware that an independent body has assessed some of their claims, validated them and granted them compensation.

“George the Lionheart was dressed with a cross on his chest and ready, awaiting his master’s return,” Fisher told the mourners at Pell’s funeral. “His influence has been far-reaching, and we can be confident will long continue.”

It is true that it is hard to overstate the Pell legacy on the Catholic Church, most particularly in its robust and increasingly defensive legal response to victims of child sexual abuse, infamously formulated as the “Ellis Defence” on Pell’s instruction to his solicitors, and now perpetuated with other legal technicalities designed to avoid liability.

This essay will explore how that legacy is continuing to thwart survivors’ chances of being compensated for their lifetime of pain, and how, just as in Pell’s lifetime, the Catholic Church is still prepared to go all the way to the High Court to avoid damages.

The most successful legal tactic currently being used by the church – upheld by the High Court in November in the Bird v DP case, appealed by the bishop of Ballarat, Pell’s home diocese – is that members of the clergy are not “employees” of the church, and therefore it cannot be vicariously liable for abuse perpetrated by them. This is despite the fact that priests may receive a wage or stipend, superannuation, annual and long service leave, a car allowance and free accommodation. (Bishop Paul Bird confirms to The Monthly that the priests of his Ballarat diocese received the JobKeeper payment during the Covid pandemic.)

It’s a strategy that is glaringly similar to the Ellis Defence that was cultivated by lawyers for Pell’s archdiocese of Sydney, which said the trustees of the Catholic Church had no legal personality and therefore could not be sued. Legislators around the country removed the Ellis Defence following the royal commission’s final report in 2017, but when it comes to devising ways of escaping the payment of compensation to victims of child sexual abuse by its clergy, the church’s lawyers are doggedly creative.

Having last year been defeated in the High Court on trying to invoke permanent stays to stop victims of dead or demented clergy from being able to go to court at all, the church has now had a stunning success with the case appealed by Bishop Bird, against an award of damages to a complainant of clergy abuse. It avoided vicarious liability on the basis that, effectively, clergy are employed by God, not dioceses, and, by extension, not schools or orders.

This new legal landscape, which has prompted the country’s attorneys-general to now consider law reform, has resonance for some of Pell’s victims, including David, who are currently suing church bodies.

David is suing the diocese of Ballarat, whose bishop confirms he was one of the attendees at Pell’s funeral. Bishop Bird didn’t answer questions about his reasons for attending, after having been put on notice only weeks before that he was to compensate David for abuse that the scheme found was committed by Pell.

Two years on from Pell’s passing, David and the other victims are disgusted by the way the church has attempted to burnish Pell’s reputation and avoid admitting liability for what he did. Once vulnerable boys, they have been, until now, the church’s secret.

The sun rose, the moon burned in the night sky, the truth was obscured from public view.

Now, the men are standing up for the little boys that still live inside them.

David grew up in George Pell’s Victorian home town of Ballarat but has lived both interstate and overseas for many years. We’re using his middle name because of his employment as a teacher.

He was a “water victim”, one of many men I’ve spoken to over the years who make allegations that Pell engaged in abusive or inappropriate behaviour while they were swimming at Ballarat’s Eureka and YMCA pools, Swan Hill’s Lake Boga, Phillip Island’s Smiths Beach or Torquay Beach.

The water-related complaints about Pell typically involve horseplay, often involving games where, for instance, the priest would put one hand under an arm and another in their genital region and grope them before throwing them into the air. Alternatively (and sometimes to the same victims), he would expose himself to children in change rooms.

He would, in the words of the victims, touch their bums and their testicles, squeeze their genitals, sometimes in a more fleeting way and sometimes in a harder way that frightened them, and stand naked, inviting them to towel down with him, sometimes giving them instructions about how they might dry themselves: We’re all men here, that sort of thing.

The water victims such as David never forgot it: they were angry and traumatised enough about what they alleged Pell did to them to make complaints to police, to church bodies, to the redress scheme and to solicitors.

The steamy day I meet David far from Ballarat in the subtropical city he now calls home, he tells me that all his life he was an obsessive fan of the late and celebrated American novelist Cormac McCarthy. But having seen the recent controversy surrounding McCarthy concerning suggestions he groomed a homeless teenage girl to become his lover, David informs me that’s it: he has thrown his entire McCarthy collection in the bin, bar one rare edition given to him by his kids. He just can’t look at the books anymore.

David had two abusers – Pell and a Christian Brother in Ballarat about whom there have been numerous other allegations.

Although it was David and his wife who reached out to me nearly two years ago, it’s been a huge decision for him to speak to me now. Like many survivors, he has trust issues. Given what happened with Pell and the Christian Brother, and the lionising of Pell even after the findings about him have come out, those trust issues seem well-founded.

David was in Year 3 at St Patrick’s Primary School – known to locals as “Drummo” because it’s on Drummond Street – and on an excursion to the YMCA swimming pool when, the National Redress Scheme decision-maker found, Pell grabbed his genitals to throw him in the air.

In David’s statement he said that Pell would lift him “with his hand at the front of my crotch – essentially grabbing my genitals and throw me that way”.

“The whole manoeuvre was pretty dodgy in the extreme by today’s standards – possibly even so by 1970s standards,” David wrote, adding that it made him “uncomfortable” at the time.

“It was (and is) preposterous to think that there was anyone I could go to and ask is it OK for George to place his hand on my genitals,” he wrote. “I did not even have the language to pose such a question never mind a person to pose it to.”

David’s account was accepted by the National Redress Scheme’s decision-maker. The scheme’s decision-makers include retired barristers, police, psychologists and senior public servants, assessed to have a strong understanding of the cultural, social, historical and political factors relevant to its operation.

When the scheme was introduced, the president of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference, Brisbane’s Archbishop Mark Coleridge, welcomed it.

“We support the royal commission’s recommendation for a national redress scheme, administered by the Commonwealth, and we are keen to participate in it,” Coleridge said in 2018 when the church signed up to the scheme. “Survivors deserve justice and healing and many have bravely come forward to tell their stories.”

The decision-maker in David’s case said that while David’s memories of something that happened almost 50 years ago are understandably “sketchy”, he appeared “candid and not exaggerated”, and he was “psychologically uncomfortable being grabbed”. The finding asserted that “the children could be thrown without touching genitals (holding under arms or feet)”. It was not “incidental touching” and it was contrary to community standards of the time.

Crucially, the decision-maker also made reference to the fact that similar other claims of sexual activity by Pell had been made, although they redacted those details.

The diocese of Ballarat, via Bishop Bird, declined to comment on David’s case. Bird said he believed the National Redress Scheme prohibited him from speaking about cases.

Three of the water complainants spoke to me on camera almost nine years ago for the ABC TV 7.30 program, and their stories, along with those of a fourth who came forward to me after that report, are featured in my book Cardinal: The Rise and Fall of George Pell.

One of those men, a lifelong alcoholic who told me his mother slapped him around the face with a shoe when he tried to talk about abuse by a teacher at St Alipius Parish School in Ballarat, died in 2018 at the age of 48, three months before Pell’s committal proceeding in the Melbourne Magistrates’ Court.

A second was to be one of the complainants in the so-called Swimmers’ Trial, to follow the St Patrick’s Cathedral Trial in the Victorian County Court in 2018. The Swimmers’ Trial was to involve three men who had been part of the Pell committal proceeding in March 2018 and whose allegations Magistrate Belinda Wallington felt held sufficient weight to have Pell stand trial on those charges.

The Swimmers’ Trial was abandoned after County Court Chief Judge Peter Kidd decided that the evidence of three complainants could not be heard together because of the technicalities of tendency evidence – each trial would have to be heard individually. The Office of Public Prosecutions decided that it would be onerous for the men to proceed individually, and it felt satisfied that a conviction, which it then thought secure, in the Cathedral Trial, had already been obtained. Hence no ruling was ever made about the verity of the swimmers’ claims by a judge or jury.

After the trial was abandoned, my Four Corners story “Guilty”, about the conviction of Pell, was broadcast. That prompted David, who would later be granted redress, to contact police in writing and, six months later, to visit Ballarat Police Station in person. He says he was told by the constable on the front desk that he was “two years too late”, and the officer he then spoke to doubted whether the abuse he alleged crossed the criminal threshold. Having kept the abuse to himself for so long, David was hurt and angry, and complained to Victoria Police’s professional standards unit. The officer in question was counselled.

One of the other men in the abandoned Swimmers’ Trial is now suing the church for his abuse by Pell and a nun, Sister Luke of the Sisters of Mercy, who worked at St Alipius. The impact of the abuse by the nun and Pell on that man is enormous. Victoria Police’s Taskforce SANO is believed to have interviewed many people about her, and the man’s allegations about her abuse are detailed and chilling. She died in 2021.

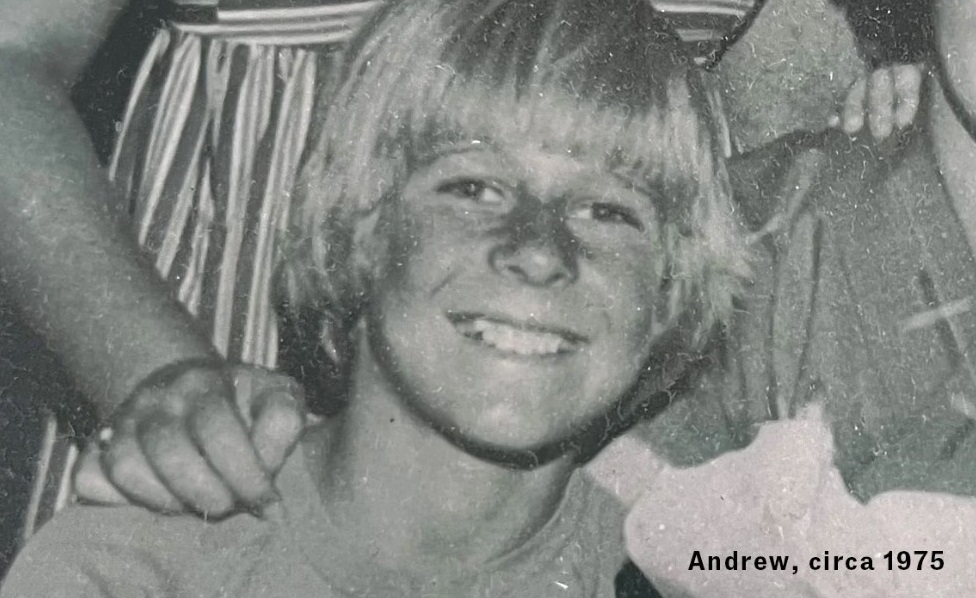

For this essay, the remaining two men who were to be in the Swimmers’ Trial, Livio and Andrew, are speaking publicly for the first time.

Livio, who runs an earthmoving equipment business, grew up in Ballarat East. He’s a big bear of a man who looks you straight in the eye and, thanks to many years of counselling, feels he has nothing to be ashamed of. He had no interest in watching Pell’s funeral, but he does remember the first moment he heard that the cardinal was dead.

“I just thought, Good fuckin’ riddance,” Livio says. “Sorry, sorry,” he adds, holding up his hand and apologising for his language.

He has a message for the Pell apologists who attended the funeral and maintain he was the victim of a witch-hunt.

“I think you have been completely led astray by your beliefs,” he says. “You need to understand what every single one of us is going through …

“And I hope that your children, or your children’s children, never go through what we have gone through and to the point where they’re not believed.”

Livio tells me he was devastated when staff from the Office of Public Prosecutions and Victoria Police called him to a meeting at Ballarat Town Hall to tell him that the Swimmers’ Trial would not proceed because the men’s allegations could not be heard together.

“I was just sitting there, dumbfounded. I didn’t know what to say, I didn’t know what to feel.”

He remembers that the cross-examination by Pell’s barrister in the committal proceeding made him cry and Magistrate Wallington had excused him at one point to recover.

“I’ve just gone through fricking hell and the whole system has basically let me down, trying to get someone to be accountable for what they’ve done and then you find out it’s all gone.”

Livio found out shortly after the Director of Public Prosecutions’ visit to Ballarat that there had been a conviction in the Cathedral Trial, and that gave him some succour. But he was, he says, “a mess” for some time after that, and he’s done a lot of work with counsellors and advocacy groups since then to bring himself back from the brink.

At its worst, the depression that the abuse caused Livio got him to a point where he once drove into the path of an oncoming truck. But he thought of his child and partner and swerved to safety.

We’re sitting in the kitchen of the house in Ballarat where Livio grew up, just up the road from the school and the swimming pool where he says his abuse took place. It’s one of those little ’50s brick homes that looks like a Howard Arkley painting, with fruit trees and a vegetable garden out the back that Livio’s staunchly Catholic Croatian parents planted long before his dad died and his mum went to a nursing home.

Livio went to St Alipius, where a ring of paedophile brothers and a priest terrorised the children, including the little Croatian-Australian altar boy who was teased mercilessly as a “wog”. He didn’t tell his parents about the abuse he received from Pell at the pool and notorious paedophile Brother Gerald Fitzgerald at St Alipius – he was afraid that he’d cop a belting. His fears weren’t unwarranted.

On one of the occasions that Brother Fitzgerald had abused him, Fitzgerald had, Livio says, found him in the toilets unable to get the fly on his trousers down.

“And he’s come up behind me and undid the fly and pulled it down, and yeah, I literally flaming panicked – What the frigging hell? – and got a dribble out and I walked down … I was pissing my pants all the way up through the toilets, just to get the frigging hell out of there.

“Came home smelling like urine. Bloody Mum’s given me a hiding. Dad’s given me a hiding.”

It’s hard to look at the First Communion photo of eight-year-old Livio, with his mop of blond hair, his stiff 1970s suit and his jaunty black bow tie, and think of the fear that was coursing through this little boy’s veins about his Year 3 teacher. Livio’s statement about Fitzgerald, who died in 1987, says that “Fitzy” would regularly fondle Livio’s genitals, insist on swimming naked, kiss and cuddle him on his knee in class, lift him by the ears and throw him on the floor and, at the most extreme, made Livio hold an electrical generator to receive electric shocks as Fitzgerald wound it.

Livio was in the same class as the older brother of one of the other men meant to be in the Swimmers’ Trial, although he did not know the fellow Pell victim beyond a passing hello. The older brother died by suicide – another part of the painful history that has the surviving brother now, after going public for the 7.30 program because he wanted the world to know that Pell was a paedophile, just trying to recover in peace.

It is in the context of Livio’s fear of “Fitzy” that, a couple of years later, he was confronted by behaviour from Pell that made him feel uncomfortable and afraid.

Livio remembers that in the summer of 1977 or ’78, when he was 10 or 11, he would regularly see Father Pell, whom he knew from Pell’s occasional masses at St Alipius, at the Eureka pool, playing games with the boys. Pell was during those years the episcopal vicar for education for the Ballarat diocese, which spans western Victoria.

“He was like a magnet to all the male kids at the pool,” Livio told police in his statement.

“Once everyone became aware that Father Pell was there, all the kids would go down to the shallow end to play with him.” Livio says that he would watch Pell throw the kids with one hand under an arm and the other either on one “bum cheek” or both.

This is a story I have been repeatedly told by men who were children in Ballarat at the time, including those who did not make allegations of abuse against Pell.

But Livio’s account of the abuse is also incredibly similar to others who say they were abused at the pool by Pell, and those who say they were abused in other bodies of water.

The first incident is one where Livio saw Pell in the change rooms when no one else was present, went to the toilet and came back to find the priest still there.

“He was standing naked in the change rooms with a towel draped over his shoulder,” Livio told police. “Seeing Father Pell naked in front of me scared the shit out of me. He wasn’t trying to be discreet and seeing a member of the clergy naked like that was off-putting for a kid.

“Father Pell then said to me, ‘If you need to have a shower or change, it’s okay. We’re all men here.’”

Except that one of them wasn’t a man – one of them hadn’t left primary school. Livio now explains to me that he has never before or since seen a man act as brazenly while naked with a boy in a change room. They always cover themselves up or turn their backs, or move to a corner.

This echoes the account of Darren Mooney, another Ballarat kid at the time, now a school principal, who spoke to me for the 7.30 program and Cardinal, as well as the account of Les Tyack, who saw Pell do something similar with three young boys at Torquay Surf Life Saving Club in the 1980s and warned him to piss off and never come back there again.

Livio’s own fears about Pell were heightened when he was in the pool and Pell did his famous throwing game, with his hand on Livio’s right buttock. Livio says it felt like Pell touched one of his testicles.

“Once I surfaced from the water, I said to myself, What the fuck was that?” Livio told police. “I felt very uncomfortable and knew that it wasn’t right in the way he threw me by touching my bum cheek and testicle.” Livio got out of the pool and vowed never to return while Father Pell was there.

Chief Judge Peter Kidd noted in his judgement, where he decided not to hear the swimmers’ allegations together, that the touching of Livio’s testicle could have been accidental, however, as the redress scheme decision-maker in David’s case pointed out, there was no need for Pell’s hands to be anywhere near the children’s genitals anyway. Hence, the decision-maker said they were in part reasonably satisfied (the test for granting redress) that the “play” activity in the pool constituted a sexual activity.

A year to the day that Pell was acquitted by the High Court, on April 7, 2021, Livio was paid a $350,000 financial settlement in a civil case brought in relation to abuse by Gerald Fitzgerald and Pell. The Christian Brothers sent an apology to Livio as part of that settlement.

“Livio, I commend you for the courage and perseverance to bring your complaint to our attention,” Shane Wall wrote on behalf of the Christian Brothers Oceania Province, saying that the conduct of Fitzgerald he described was “reprehensible” and a “gross betrayal of the trust you have every right to place in every teacher”.

But while the Catholic Diocese of Ballarat was also a signatory to Livio’s deed of release in relation to his allegations of abuse by Pell, it did not apologise to him for the actions of the cardinal. The deed says of all of the abuse, including that of Fitzgerald, that the existence of the settlement cannot be considered an admission of liability.

Bishop Bird declined to comment on Livio’s case.

Andrew was one of a family of “seven little Australians”, as his dad Colin puts it, who grew up in the ’70s in Swan Hill, on the Murray River in Victoria’s north-west, and, like Livio, he was an altar boy.

Andrew says he was subjected to horrific and violent abuse by Gerald Ridsdale, possibly the Catholic Church’s most prolific paedophile offender, in the presbytery at St Mary’s church when Ridsdale was visiting there as a priest in 1974.

Apart from repeatedly forcing oral sex and attempting anal sex with Andrew, and getting angry with him because he couldn’t penetrate him, Ridsdale would, Andrew says, frequently punch him in the stomach and hit him on the head.

“One of the most common things was slap me in the side of the head really hard,” Andrew tells me on the phone in December. “Like, hit my ear, which was really painful when you get [it] in the ear when it’s a flat hand.

“It’s like he knew what he was doing. It’s the one thing that I can never get out of my head. The worst part about it was every time he did it, he would watch me, really intently. It was just weird.”

The year before Andrew’s abuse, Ridsdale commenced living in the presbytery at St Alipius in Ballarat with George Pell. He was many years later infamously photographed being accompanied by Pell to court during one of his hearings for the multiple crimes for which he has now been convicted.

The child abuse royal commission found that Pell, who was a consultor to Ballarat’s Bishop Ronald Mulkearns when the bishop was moving Ridsdale from parish to parish, knew about Ridsdale’s offending and did nothing to stop it. The commissioners found that it was “inconceivable” that Mulkearns lied to Pell and the other consultors about why Ridsdale was being moved on, rejecting a key plank of Pell’s evidence to them.

“We are satisfied that Bishop Mulkearns told the consultors [including Pell] that it was necessary to move Ridsdale from the Diocese and from parish work because of complaints that he sexually abused children. A contrary position is not tenable,” the commissioners wrote.

Andrew’s allegations about Ridsdale predate the knowledge that the commission found Pell had of Ridsdale’s activities.

As he is describing a particularly gruesome incident with Ridsdale, Andrew weeps openly.

“I’m really sorry,” he keeps saying. “I’m sorry I’m really upset. It needs to be said, though.”

He says that Pell would visit with Ridsdale, and that Pell would describe Andrew as “my boy”.

“When he called me his boy, they both looked at each other, and – you know that look? Knowing? That’s the way they looked at each other, this little private joke between them,” he says.

“I didn’t understand, because I was a kid – only years later I realised.”

One day when Andrew and his family were waterskiing at nearby Lake Boga, Pell turned up and proceeded to play one of his water games, where he was holding the altar boy in the “groin area” as he catapulted him into the lake.

“I jumped off his shoulders, I slipped down, facing him, and he had an erection,” Andrew says.

“I felt that straight away. He had this stupid grin on his face, and he said, ‘Don’t worry, it’s all right’.

“It’s making me so angry thinking about it. How dare a person do that to someone at that age?”

Lake Boga is, Andrew explains, a “muddy sort of lake”, so you can’t see under the water. He didn’t know about the erection until he slipped down in front of Pell and tried to grab hold of him to stop himself from going under.

“And I’ll never forget the look on his face, the fucking bastard … I must have looked shocked. He said, ‘Don’t worry, it’s all right, it’s only natural.’”

I just listen, but speaking about this makes Andrew cry again.

“When I get upset, don’t worry – it’s not because I don’t want to talk about it. I want to talk about it. I know now that I’ve got to speak up. I’m not going to get over it otherwise.”

Andrew’s family knew another family in Swan Hill at the time with an older son who had also been an altar boy – Stephen. Stephen’s father was a local policeman. Unbeknownst to Andrew, Stephen was also granted redress and a letter of apology after making allegations about Ridsdale and Pell’s behaviour in the presbytery at St Mary’s.

Stephen, who died in December last year and who was a long-term alcoholic, also told both Victoria Police and the redress scheme that he had been the subject of unwanted attention by Pell – whom he said invited him to have dinner at the presbytery and to sleep the night if things went well, even though Stephen lived just a short bike ride away.

He told the scheme that Pell sent him to an upstairs room in the presbytery and that Ridsdale touched him on the inner thigh and said he wanted to get to know him better.

Stephen had approached me, through a friend who was an intermediary, in January 2018, as I was preparing to be a witness in Pell’s committal proceeding – a process that was extraordinarily stressful. At that time, I was unable to report on Pell because of the laws of sub judice and my role as a witness in the case. Stephen spoke to another journalist, Lucie Morris-Marr, who was covering the trial, and she published the details after Pell was convicted. He later also spoke to Victoria Police’s Taskforce SANO and offered to be a witness in the Pell trial if needed.

When Andrew got in touch with me again, and I discovered the detail of what happened with Ridsdale and Pell, I tried to reach out to Stephen on various platforms but all were silent – it was only when I contacted his friend and family that the friend told me he’d sadly died the year before.

As with Livio, Andrew’s experience of the Pell committal proceeding was gruelling. He says he was accused by Pell’s defence counsel of making it all up and angrily denied it.

“To be honest, I wanted to kill that guy there and then. I am not a violent person at all,” Andrew says.

When he was telephoned to say that the Swimmers’ Trial wouldn’t proceed, he says he was furious with the whole process, which he didn’t understand.

“It fucked me up big time, to be honest.”

Andrew, a former member of the Navy who was decades ago placed on a disability pension because he was unable to work after a catastrophic accident while on duty, contacted me late last year.

I have been in correspondence and telephone contact with him on and off for four years via his father, Colin, who, like me, was a witness in the Pell committal proceeding and, like me, was confronted by the way he was treated in court.

When Andrew got back in touch with me in November, he had decided with his psychologist that he finally needed to speak his truth. He has never been interested in civil compensation, which he sees as “dirty money”, but he felt that speaking out was his way of putting this issue to bed.

Unfortunately, with this sort of trauma it’s not that simple.

Andrew remembers the day that Pell died. Colin, a dear and caring man in his 80s who just wants the best for his boy, rang him to tell him the news.

“I burst out laughing and crying at the same time,” Andrew remembers.

He was among those on my mind the day of Pell’s funeral. Like Andrew and Livio, I couldn’t bring myself to watch it at the time. But I finally sat down and watched the whole thing in December, nearly two years later.

Archbishop Anthony Fisher told mourners that Pell’s prison diary was “one happy fruit from 404 days spent in prison for crimes he did not commit” and joked about the “leonine old-timer” who had a love of seminarians. Pell’s brother David declared that the family sympathised with “legitimate victims” but that what was said about Pell was “not true”, citing a “relentless smear campaign”.

“We implore you to rid yourselves of the woke algorithm of mistruth, half-truths and outright lies that are being perpetrated,” David Pell told the congregation. I supposed that in his eyes I was part of that woke algorithm.

I got to Tony Abbott’s speech. The former prime minister uttered these words: “In short, he’s the greatest Catholic Australia has produced. And one of our country’s greatest sons.”

As I listened to the crowd erupt in loud and lengthy applause in response to Abbott’s declaration, my phone rang. It was Andrew. He was in hospital again. The hairs on the back of my neck stood on end.

Andrew was wanting to speak up, and yet every time we talked, he would cry or apologise. “I’m sorry, Louise, I’m sorry,” was one of his constant refrains.

“You’ve got nothing to be sorry about,” was mine.

Andrew still believes in God. So does his dad, who still goes to mass. They just don’t believe in the church of Pell.

Several times in December, Colin told me he worried he was going to lose Andrew, so scarred as he was by his time as a boy in Swan Hill. My plans to fly to Sydney to visit him, as I had with David and Livio, had to be put on hold while Andrew gets some treatment.

I was able to drive to Ballarat to meet James and his mum, Carmel, in the unit where they live. James is resolute about his decision to come forward, and the National Redress Scheme’s finding that he had been abused has provided some degree of validation.

James was a chef for many years, though he can’t work now due to his health, and Carmel has been an advocate for a Ballarat survivors’ group for a decade. But she had no idea that her own son was a survivor of a brutal rape by Pell.

When I arrive at their home, Carmel wheels towards me and clasps my hands. She is a woman who radiates kindness, once a committed Catholic who was very actively involved in the local church community.

“I can’t believe you’re here, darling,” she says, already teary, not letting go. James is standing shyly off to the side. He is a man of few words, and he apologises to me for that, but his expression says a lot.

When I shake his hand, he has those eyes they all have – the PTSD eyes I tried to describe in Cardinal, and which Robert Richter KC referred to sarcastically when he cross-examined me in the committal proceeding for Pell, pointing out that I don’t have a qualification in psychology.

James’s eyes are small and blue and look tired, shy and vulnerable. As well they might.

His skin has the beaten look of someone who, as he later tells me, started drinking 15 cans of beer a day at age 14 when he got a job in a kitchen. Carmel was exasperated that her once studious boy was just not able to attend school anymore, but now she understands. His medical record shows bouts of alcohol-induced chronic pancreatitis, depression and an “overdose with Medicinal Drug”.

James’s First Communion photograph shows a little boy with a bowl-cut hairstyle sitting with his hands clasped, wearing a white shirt, tie and shorts, a medal around his neck for the occasion. His redress claim says he was abused soon after this time.

The redress scheme’s decision-maker found that when James was in Year 4 at Ballarat’s St Francis Xavier Primary School – colloquially known by its historical name “Villa Maria” – George Pell abused him.

Pell coached the school’s football team – James’s First Communion certificate states that he “received the Blessed Eucharist for the first time” on September 19, 1976, and is signed “Fr George Pell” in that distinctive handwriting I have seen so many times before.

Carmel had known Pell, who was a couple of years younger than her, since he was a star footballer for St Patrick’s College Ballarat, and she wasn’t keen on him.

“I never liked the man at all,” she says. “I mean, I was 14 when I first knew him. I was a student at high school, and he was Mr Big at St Pat’s, and Mr Big everything. And then, when he came into the church, I always sensed… it was just a creepy feeling.”

Carmel had sent her children to Villa Maria because she had heard rumours about the brutality of the Christian Brothers at St Alipius.

“I knew I didn’t want my children in an unsafe atmosphere,” she tells me, an irony that now hurts her almost physically.

The redress scheme decision-maker accepted James’s account of him watching Pell coach the school’s football team and stealing the priest’s cardigan, and that Pell had chased him into the nearby school gymnasium. It accepted that he was then raped.

“The gym was empty,” James said in his complaint to the scheme, and “inside the gym there was a small trampoline, and he put me on it. I remember him saying ‘Pull your pants down.’ I thought he was going to whip me with his belt. He didn’t.

“He put something in my ass – I presume it was his penis. It was very painful. I was bleeding from my bottom afterward. He then left me in the gym.”

No part of this account is disputed by the decision-maker.

While a criminal court’s standard of proof is “beyond reasonable doubt” because it can end with the deprivation of a person’s liberty, the redress scheme’s standard is characterised as “reasonable likelihood”. It receives statements and supplementary evidence from both the complainant and the institution.

Part of the horror for Carmel, a horror she is still trying to process, is that James had come home and told her that he’d stolen Pell’s cardigan, and that the priest had chased him into the gym, but that he’d belted him. This was a story that the family always remembered, and joked about darkly, as Pell rose through the ranks of the Catholic Church.

James wasn’t able to tell his mother the truth that day, or for 50 years – not fully until last year, when he finally wrote it all down for his redress application.

“I read the statement,” Carmel says, “and there it was. You just think, How have I neglected this child this way? I haven’t felt the same [since he told me]. I am just tortured by the fact that for 50 years he’d lived alone with that horror.

“And I’m just so grateful that he is who he is, because I love him dearly.”

“I was too scared to tell people what happened,” James wrote in his redress application. “In recent years I have told the Ballarat psych services that I was sexually abused as a child – I never told them the name of who did it, though.

“I am scared that people won’t believe me.”

The sun shines bright and harsh, the moon falls behind the clouds, the truth is sharp and painful.

James did ring the local police sometime after it was made public in 2016 that Pell was being investigated, but he changed his mind before making a statement. Then, in October 2022, he contacted a law firm that has had dealings with three other Pell complainants I know of, but which has referred them on to other lawyers who are now handling civil claims. In James’s case, he was ultimately referred to the National Redress Scheme.

After his redress application was made and the church was notified, he says he ran into Bishop Paul Bird at a library.

“He said, ‘Oh, what’s your name?’” James gave the bishop his full name. “He just turned his back … He just snubbed me. He completely snubbed me.”

Bird offered no comment when The Monthly put this account to him.

James was awarded $95,000 in compensation by the redress scheme, which is capped at $150,000, and the diocese of Ballarat was notified. The diocese did not accept his abuse, nor that of the other complainants that the redress letter to James states came forward and contributed to the decision-maker’s reasoning in upholding his claim. Bird declined to comment on James’s case, saying he believed government regulations required him to keep details of claims confidential.

James would have been entitled to far more in a civil case. I have spoken to abuse lawyers whose clients have received settlements that are more than a million dollars, and half a million is not at all uncommon.

For James, it was never about money. He lives a quiet life at home with his beloved mum. It’s about validation – that someone, an official government body, accepted that he was telling the truth.

In David’s case, he was relieved to receive the validation of the redress scheme but sought legal advice before accepting it. His solicitors, Arnold Thomas and Becker, advised that it was best for him not to accept the $45,000 he was awarded but instead to press on with a civil claim, as he would likely receive a settlement far higher and, once accepted, a redress payment is “iron-clad”. That is, you cannot then sue an institution for compensation.

At that time, given all these factors, this was fairly standard advice.

Then Bishop Bird appealed all the way to the High Court in the case of Bird v DP and succeeded in overturning a $200,000 damages payment to a man who says he was abused as a five-year-old by paedophile priest Bryan Coffey. Bird won the case of Bird v DP in November, on behalf of the diocese of Ballarat, on the basis that the court was persuaded Father Coffey was not technically employed by the diocese. He was a priest, doing God’s holy work. The diocese of Ballarat was not vicariously liable for the abuse perpetrated by Coffey.

“It’s particularly relevant and poignant because [David’s] pursuing the very same defendant in the diocese of Ballarat that took DP [a pseudonym] to the High Court,” David’s solicitor, Kim Price, tells me.

Price is not giving up on David’s case, and he and solicitors and barristers around the country are searching for ways to argue these cases.

“Since the royal commission,” Price says, “there have been so many positive developments, and it got to the point where survivors were achieving just and reasonable outcomes that compensated them for the devastating losses that they suffered.

“They no longer have to face technical defences like the Ellis Defence, but this decision [in Bird v DP] has created a situation that some survivors find themselves in, back to those dark old Ellis Defence days.”

While Bishop Bird is entitled to take legal points in defence of the diocese of Ballarat, Price finds the hypocrisy of the church’s public messaging on this galling.

“You can find so many public statements that the Catholic Church has made in terms of its reforms and its approach and recognition of the damage that’s been suffered, but at the same time, they avoid all legal responsibility based on an argument that their priests – the individuals they have sworn to follow all of their rules and canons and laws – they have no responsibility whatsoever for them.”

He says his clients don’t understand how clergy are not employees.

“There’s a level of disbelief because it’s so far removed from modern community expectations and standards that organisations like that that have been responsible for care of children can avoid liability … You’ve got to explain it [to the client, that] even though a priest is more subservient [than ordinary employees and] controlled by a diocese, the courts have said, ‘Sorry, the church has got no responsibility here’.

“That’s where survivors and, I think, most people in the community are gobsmacked.”

There are so many gobsmacking aspects to this. For instance, one document dated 1976, tendered to the child abuse royal commission about a sacked paedophile priest, Paul David Ryan, is a Department of Social Security “Employment Separation Certificate”. Under “Employer Details”, it lists “Roman Catholic Diocese of Ballarat”.

Sangeeta Sharmin, the solicitor who acted for DP in the case against Bird, points out that in the United Kingdom and Canada, courts have extended the notion of vicarious liability to people including clergy in roles akin to employment, but says the High Court of Australia has thrown down the gauntlet to legislators to amend the law.

“I think everyone [involved in our case] felt hopeful – we had everything going our way,” Sharmin says of the lead-up to the High Court’s judgement. “We won the three interlocutory proceedings, the trial, the appeal, and at the [High Court] hearing, in terms of the questions we were asked, it seemed positive.”

She says she did a double take when the decision was emailed through.

Like other solicitors around the country, the firm is writing to and meeting with state and federal attorneys-general to plead the absurdity of the law.

Bishop Bird says he appreciates “people’s concern for those who have suffered abuse and people’s questions about organisations accepting responsibility”.

“In cases where there is evidence that the diocese of Ballarat has been negligent in the duty of safeguarding children, the diocese accepts liability, without the need for liability to be proven in court, and the diocese provides compensation to victims,” he says.

Negligence requires the diocese to have had actual knowledge of the abuse occurring, as distinct from vicarious liability, which holds that the diocese should be liable for abuse by members of the clergy working for it whether the diocese knew or not.

Bird says the diocese will also continue to provide counselling, pastoral help and compensation through the National Redress Scheme and through a church process called Pathways Victoria. Pathways Victoria compensation is capped at $333,707 – just over double the redress scheme’s maximum payment. By contrast, the largest compensation payment in a civil claim for a sexual abuse survivor in Australia was awarded in a Victorian state school case in October last year. It was $8 million plus costs. There is serious money to be saved by institutions in fighting these cases and devising defences that ordinary members of the public struggle to comprehend.

A fluorescently lit courtroom high above Phillip Street in Sydney is a window into this technical morass. Sitting in the room is one of the very same legal minds that George Pell employed in his lifetime to avoid liability for a victim’s abuse by a priest.

It’s hard to marry the bland, beige room, the white men in wigs and the use of phrases like “non-delegable duty” with the strange and sad reality of a story from outback New South Wales that brought them all here.

The case was brought by a First Nations man, Albert Hartnett, and it involved allegations by him that he was beaten by a now elderly Sister of Mercy, Sister Marietta Green, when he was a small child between 1992 and 1994 at St Ignatius Parish School, Bourke, in north-west New South Wales and within the Catholic diocese of Wilcannia-Forbes. Green denies the allegations.

Hartnett alleges that when he was in the infants’ school at Bourke, he and other children were belted with a large ruler that the nun referred to as “Montgomery”. He also alleges abuse by an Aboriginal liaison officer who was employed by the diocese. In the post Bird v DP legal climate, Hartnett finds himself in the absurd situation where the church might be liable for the actions of the reasonably junior liaison officer, but not the nun who worked and taught alongside him. That is, the person who, in the scheme of things, was far more responsible for the care and safety of the children at St Ignatius, was employed by God, not the church school she worked in.

“I’ve only had one success story with Aboriginal children, a young girl doing law at the University of Sydney,” Green, famed in the region for her “Aboriginal-only” classes, told The Sydney Morning Herald when she was leaving Bourke in 2005. “[But] if you look for results in a place like Bourke you wouldn’t stay …

“I try to minister without judgement and let them know I love them and will do anything I can to care for them.”

That is not the account of the numerous clients of Sydney solicitors Michelle Martin and Tatiana White, including Hartnett, for whom they are acting in complaints against the nun. The allegations against Green by other complainants are also denied.

“We had about 15 witnesses who came to court to give evidence,” Martin, from the firm North Star Law, says. “This included a parent who had complained and other former students who allege they also suffered abuse by Sister Marietta. Another was a man from Adelaide taught by Sister Marietta before she came to Bourke – he had no relation to the others but was also hit with the ruler and never forgot it.”

Photographs of Green show a beaming, diminutive lady who looks like a storybook kindly nun. But Harnett’s statement of claim creates a more disturbing picture.

It says that on one occasion he was hit on the back with a ruler so hard that it broke. On another, it says Green took down his pants and hit him with the ruler on his bare bottom, unintentionally catching his penis.

“On occasions, Sister Green grabbed the Plaintiff by the ears, twisted his ears and dragged him,” it says. “On occasions, Sister Green made [Hartnett] stand outside under the sun for a prolonged period of time.”

Green has denied all the allegations made against her by Hartnett.

There are three defendants in this case: the Sisters of Mercy, the Marist Brothers, who ran the school, and the diocese of Wilcannia-Forbes, in which it was located.

In February last year, when the trial ran, a barrister acting for the diocese of Wilcannia-Forbes’ legal team volunteered that rather than the three defendants fighting it out as to who was responsible, in the event that they lost the case, it would be vicariously liable for Green.

That would make sense. Green worked at St Ignatius for 29 years, and her engagement at the school was referred to in 2003 correspondence between the Sisters of Mercy and the diocese that ran the school as “continued employment” that was by that time on a “part-time basis”.

“In my personal view, a member of a religious order teaching in a school must be in a legal relationship,” Martin says. “They are teaching the children alongside lay employees. Generally for teachers there’s registration, there’s curriculum set, it’s a job, it’s got set hours. From the child’s point of view, they are a teacher like all the others. I think it’s creating a special level of protection for the Catholic Church due to their own internal structure and in a secular society I don’t think people will think that’s fair.”

The question of employment seems to be used differently by the church in different contexts.

Kevin Dillon, a priest of the archdiocese of Melbourne, wrote to Hartnett’s legal team to advise that during the Covid pandemic he was allocated a JobKeeper allowance, which he was asked to give to his parish. Further, he wrote, “I have recently been advised that in applying for a Police Check, as I am required to do, I should designate myself not as a volunteer, but as an employee.”

Acting for the diocese of Wilcannia-Forbes was solicitor John Dalzell. Dalzell became known during the royal commission as one of the key architects of Pell’s Ellis Defence at his former firm, Corrs Chambers Westgarth – Pell’s solicitors for many years.

Clergy abuse survivor John Ellis lost his case when the High Court refused him special leave to appeal because of the technical defence the archdiocese of Sydney had constructed: that its trustees had no legal personality and couldn’t be sued. During the commission’s hearing into the Ellis case in 2014, it was revealed that the costs were estimated to be $500,000 to $600,000 and Ellis’s lawyers were begging the archdiocese not to enforce them. Dalzell then wrote to Pell’s managers in the archdiocese, citing what one of the other solicitors at Corrs referred to as the “Telegraph test”; that is, “whether you would be prepared to accept the risk of this story appearing on the front page of the Telegraph newspaper (a real risk in this case, given the plaintiff’s predilection for flirting with the press)”. “The plaintiff”, John Ellis, was a lawyer. But he was also someone who had recounted years of abuse by a priest in the archdiocese of Sydney when he was a teenage boy.

“For what it’s worth,” Dalzell continued, “my own view is that although the ‘Telegraph’ test may create some negative publicity, it may also have the effect of sending a clear message to potential litigants that the Church takes these matters seriously and that they will not be given a free kick.”

Regarding Ellis, a “free kick” would be the waiving of costs by a diocese that was found in 2018 to have $1 billion in assets in Sydney alone, for a case that went to the High Court to try to compensate the lifetime of pain caused by child abuse by one of its priests.

Ellis’s lawyers continued to plead with Dalzell and his colleagues at Corrs not to enforce costs against their client, writing that he was broke, a victim of child sexual abuse and suicidal. Eventually, the church and its lawyers backed down.

It would appear from the Sister Marietta Green case that Dalzell has not changed his stance on avoiding “free kicks” to survivors, although when I approached him outside court to ask about whether he still employs the Telegraph test, he said he couldn’t remember what was said in the royal commission and its report had been finalised.

“You keep talking and not listening,” he snapped, when I repeatedly tried to ask him questions.

“I really want to listen, and that’s why I’m asking you the questions,” I replied.

But Dalzell said he had nothing more to say and walked away. He later refused to offer any comment for this essay.

Nine months after Dalzell’s barrister had put to the court that the diocese of Wilcannia-Forbes would be vicariously liable no matter what happened in the High Court, he withdrew that claim, saying Dalzell had made a misapprehension as to the way that the Bird case would go.

Since the High Court had made its decision in Bird v DP, the diocese’s legal team put to the NSW Supreme Court that it was clear that Green was, in fact, not an employee and the diocese could not be vicariously liable.

Justice Stephen Campbell in the NSW Supreme Court accepted this mistake and said that even though the correspondence about Green described her as being “employed”, it did not mean that she was, as far as the law around vicarious liability was concerned. Michelle Martin’s legal team will now have to navigate another legal avenue – a very complicated one called “non-delegable duty” that has to date not been successful in cases of deliberate harm.

In the church, you can be employed without being employed. Even if the church paid your super, regulated your hours or described you as employed in correspondence.

Introducing laws to overturn the Ellis Defence in 2018, then-NSW attorney-general Mark Speakman addressed John Ellis in the parliament directly, saying “the law failed you, but today the government says never again.

“No more will New South Wales laws permit organisations to escape liability in the way you experienced,” Speakman said. “No longer will institutions be allowed to enable child abuse by hiding behind their corporate structures, as you experienced.”

But they are.

While Pell himself told the royal commission in 2014 that he had argued the church should set up a corporation in order for it to be able to be sued by victims, plaintiff lawyers around the country have consistently told me that many Catholic dioceses and orders have been just as robust in their defence of these cases as they were before the royal commission.

At the commission’s close in 2017, archbishops including Anthony Fisher of Sydney and Mark Coleridge of Brisbane apologised to survivors for what they described as “a kind of criminal negligence” by the church hierarchy and a “colossal failure of culture that led to a colossal failure of leadership”.

Fisher led Pell’s funeral mass. Coleridge attended.

No free kicks have been given to a father of a now-deceased choirboy. Witness J alleges the other choirboy was with him when the boys were abused in the sacristy of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Melbourne in 1996.

Witness J told the court that Pell, the then-archbishop of Melbourne, forced them to give him oral sex.

The boys were 13 when the abuse that Pell was originally convicted for, and eventually acquitted of, is alleged to have happened. The year after that, Witness J’s choirboy friend went through a radical transformation from innocent and happy-go-lucky chorister to a teenage heroin addict.

His parents were so concerned they brought him to the Royal Children’s Hospital to have him assessed. He never disclosed his experiences and when asked by his mother, who intuited that he must have been the victim of some sort of abuse, he shut the conversation down.

The choirboy died of a heroin overdose at the age of 30. It was that tragedy that provided the impetus for Witness J coming forward to the police, unaware that a steady stream of other men he had never met, who lived in other towns and cities, were beginning to do the same.

The choirboy’s father is suing the archdiocese of Melbourne. The archdiocese argued – again, right up to the High Court – that he had no right, as a third-party family victim, to do so. In February last year, the High Court refused the archdiocese’s leave to appeal and the father, whom I’ll call John as there are suppression orders as to his son’s identity, was free to sue and is now seeking costs from the archdiocese.

John is terminally ill with cancer. He told me recently that he expects he has six months to live and can’t see his actual compensation case getting up in his lifetime. The church, as ever, is not backing down.

Even if John were to live on to fight this legal action, Bird v DP would again be a significant impediment to his success.

John’s case is symbolic of so many others, across the nation. So many survivors are tired and unwell, and woefully financially outmatched by the institution they wish to bring to justice. They hope the attorneys-general will hear their pleas and consider law reforms in light of the Bird v DP High Court ruling.

The Pell legacy lives on: no free kicks, don’t back down, be not afraid.

The sun sets, the moon has its dark side, and truth, as my friend and Ballarat clergy abuse survivor Peter Blenkiron always tells me, is the child of time.

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Louise Milligan is an investigative reporter for ABC TV’s Four Corners and the bestselling author of Cardinal, which won the Walkley Book Award. Among many awards for her work, she’s also the recipient of the 2019 Press Freedom Medal. Her latest book is Witness: An investigation into the brutal cost of seeking justice.