(NY)

New York Times [New York NY]

December 9, 2024

By Katherine Rosman

Saint Ann’s School hired Winston Nguyen knowing he had been imprisoned for fraud. Then someone began soliciting graphic sexual images from its students.

Less than a month into Winston Nguyen’s teaching career at Saint Ann’s, an elite private school in Brooklyn, his eighth-grade students discovered that he was a felon.

While leading an algebra lesson, Mr. Nguyen had shown the class a TikTok video, which led the students, inevitably, to search for him on the internet.

What they found was a startling torrent of headlines from about four years before, when Mr. Nguyen had been charged with siphoning hundreds of thousands of dollars from an older couple he worked for in Manhattan.

That evening, in October 2021, Vincent Tompkins, the head of Saint Ann’s School at the time, emailed class members’ parents, acknowledging the teacher’s criminal conviction and saying they had nothing to worry about.

“I can assure you that as with any teacher we hire, we are confident in Winston’s ability and fitness to educate and care for our students,” Mr. Tompkins wrote.

His promise proved hollow. Within a year Mr. Nguyen, 38, was posing as a teenage boy on Snapchat and soliciting sexual photographs and videos from students at Saint Ann’s and other local schools, according to Eric Gonzalez, the Brooklyn district attorney. This spring, Mr. Nguyen was arrested near the school. Later, he was charged with nearly a dozen felony counts. In court last week, a prosecutor said that a plea deal was in the works.

The charges have led to months of recrimination and soul-searching at Saint Ann’s, where tuition is about $60,000 a year. A law firm hired by the board is investigating how the school came to give access to its students to a man who had recently committed an elaborate fraud, and is now accused of harming children right under the noses of school leaders and parents.

Equally shocking to those who know him was Mr. Nguyen’s swift and baffling descent into criminality. A child of Vietnamese immigrants, he had risen to the top of his class at an exclusive Texas school, earning accolades for his volunteer work from Houston’s mayor before entering Columbia University.

Interviews with two dozen students, parents, teachers and former classmates — most of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity, reluctant to be connected to an article about someone accused of being a child predator — revealed how Mr. Nguyen had successfully insinuated himself into a world of wealth.

It was not the first time.

Saint Ann’s declined to make anyone available for an interview, but said in a statement, “At Saint Ann’s, nothing is more important than the safety, privacy and well-being of our students.”

Mr. Nguyen, now subsisting on public assistance and rarely permitted to leave his Harlem apartment, declined to comment.

But those who knew him before he arrived at Saint Ann’s said they have struggled to reconcile the younger Mr. Nguyen with the deeply troubled adult they would read about.

“Winston was always trying to be special, in any way, shape or form,” said Amanda Schultz, a classmate and rival throughout high school. “Maybe he’s trying to be special now by being a criminal.”

‘Gossip Girl’ — Texas Style

Mr. Nguyen’s ability to integrate himself — quickly, seamlessly, fully — into the culture of a school like Saint Ann’s did not surprise people who knew him when he was in high school.

His family lived among immigrants in Houston. But with the benefit of financial aid, he was able to attend Episcopal High School in the city’s upscale Bellaire community, where he was one of the few nonwhite students.

Episcopal, where tuition is about $35,000 a year, has educated the children of oil and gas executives and other wealthy professionals for more than 40 years. It bears the hallmarks of many elite U.S. private schools: rigorous academics, competitive sports and an emphasis on community service.

Former students describe it as “Gossip Girl” set in the oil-rich South. Mere wealth is overshadowed by great extravagance. In Mr. Nguyen’s era, it was not unusual for students to get Range Rovers as 16th birthday gifts.

Mr. Nguyen (pronounced nuh-WIN) was from a different world, but he was well-liked by many of his peers. He was seen as a go-getter and effective organizer, and as a showboat who drew attention to himself. He walked the halls carrying a clipboard and belted out show tunes like “Popular” from “Wicked.”

But he was a divisive figure, and some classmates found him to be domineering and officious.

He volunteered for school projects constantly and dressed in a button-down shirt and blazer most days. For a time, he took over an unused classroom near the school’s dance studio, turning it into an office for himself. He was smitten by the dance students and often hung around their rehearsals.

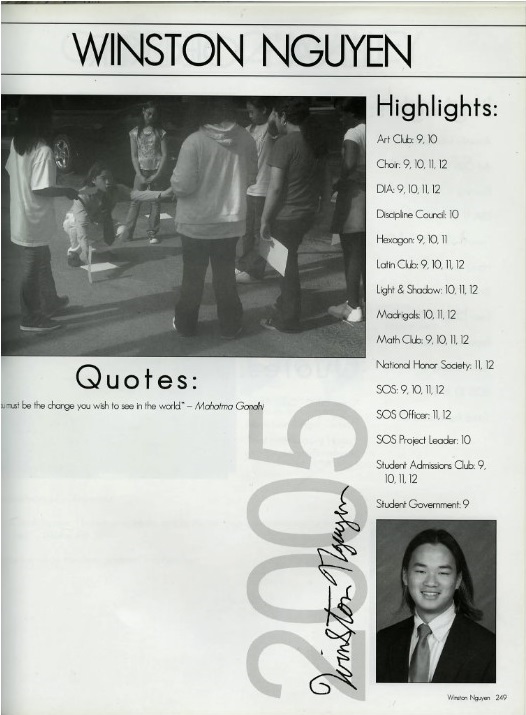

He was an aggressive joiner: art club, math club, Latin club and discipline council. He was elected class president his freshman year, running on the slogan “It’s a Win/Nguyen Situation.”

He was also deeply involved in Students of Service, an organization devoted to molding young community leaders. In 2005, Bill White, Houston’s mayor, named Mr. Nguyen, a recent high school graduate, Volunteer of the Year.

All the while, it seemed to his classmates, Mr. Nguyen was working to keep his school and home lives separate. He never spoke about his family, and his parents did not attend school events.

More visible were the relationships he forged with classmates’ mothers. One woman took a special interest in him, flying with him to the East Coast to visit colleges.

Amid his classmates’ yearbook pages filled with professional portraits and quotes dedicated to parents and friends, Mr. Nguyen’s includes a blurry photo of him as an adolescent, a school headshot showing a rock star hairstyle and a single quote: “You must be the change you wish to see in the world.”

His intelligence was obvious to his peers. Once in Latin class, he sat in the front row, looking bored as he painted his nails with clear polish. The teacher asked him to translate a phrase, and he did so perfectly, never looking up from his nails.

From the beginning of high school, Mr. Nguyen was in an open competition, encouraged by administrators and teachers, with Amanda Schultz, his classmate. Their rivalry was not friendly.

“He would say really mean things to me in class,” said Dr. Schultz, now a physician in San Antonio. “He would say that my ideas were stupid and that I was a loser.” She was equally nasty to him, she said.

In one way, Dr. Schultz beat Mr. Nguyen. Her grades surpassed his, and she was named valedictorian. But for the honor of giving a speech at graduation, Episcopal’s faculty and administrators chose Mr. Nguyen.

His speech, delivered in May 2005, urged perseverance and acknowledged the role of family support. Awkwardly, he never mentioned or thanked his own.

“I know of no other community, no other place in the world, where there are mothers and fathers like the ones we have here,” he said, “because I have never felt so loved and accepted as I do by the parents at this school.”

Although his high school career had been a triumph, the main theme of his speech was failure. “Failure isn’t the end of the world,” he wrote. “In the face of failure you have to be able to brush yourself off, get up and keep going.”

A few months later, Mr. Nguyen headed to New York to attend Columbia, propelled by the tailwinds of his graduation speech and the mayoral award.

But his college career was filled with stops, restarts and diversions. He campaigned for Hillary Clinton. He volunteered in Mexico. He worked for service organizations in Houston and New York.

In 2007, he was working with bright students from low-income backgrounds in a Houston program that was using Episcopal’s facilities. He agreed to house-sit for a dance teacher from the school and hosted a party at the teacher’s home, where under-aged students drank alcohol, former classmates recalled.

School officials opened an inquiry. They asked Mr. Nguyen to provide the names of students who had attended, and he refused, according to a person familiar with the incident.

Mr. Nguyen was barred from the high school’s property and from school-organized events, according to an Episcopal spokeswoman — including his 10-year reunion.

It was a crushing rebuke, friends said, to be cast out by the school to which he felt he had given so much.

‘Stupendous and Elaborate’

By 2013, he had returned to New York and told his family he was graduating. His father and sister traveled to the city to take part in commencement exercises, and he posed for photos in a cap and gown, according to a New York magazine article.

But he was playing dress-up. He did not earn his degree, a bachelor’s in classics, until 2019, according to a Columbia spokeswoman.

In the meantime, he worked as an aide to Bernard Stoll, a man in his 90s who lived with his wife, Flo, on Park Avenue. Mrs. Stoll had her own caretaker, but Mr. Stoll had lost his vision and needed assistance too. Mr. Nguyen helped him with daily tasks: reading the paper, running errands and, eventually, helping to manage the household finances.

Mr. Nguyen appeared to be living large in New York with a group of adoring friends, attending gala events for the city’s ballet theaters and sipping champagne and martinis with a gaggle of professional dancers.

He shared the good times on social media: sitting robed in a pedicure chair next to a dancer while on a trip to Florida, and posing with a panoply of celebrities, including Chelsea Clinton and the actors Alan Cumming and Daniel Radcliffe. He compared his life to “Sex and the City,” captioning a photograph of himself with a ballerina friend “When Carrie and Stanford go to a restaurant … ”

Friends, especially those from Houston, were concerned. How was Winston paying for this life? One visitor to his apartment spied a list of dancers’ names and the amount of money he had spent on each.

By spring 2017, the answer to how he was financing his extravagant lifestyle became clear to Veronique Perrin, formerly a daughter-in-law of Bernard and Flo Stoll.

Ms. Perrin heard from her daughter that something was awry with Flo’s credit card. When Flo or her caretaker tried to use it, the charges were often denied.

Ms. Perrin, a real estate agent, investigated. She found the Stolls’ bank and credit card statements and noted something suspicious. They were printed on just one side of paper, rather than front-and-back.

She contacted the credit card companies and learned that some of the couple’s statements were being mailed not to their Park Avenue home but to a Harlem address.

After going through mountains of statements and canceled checks, Ms. Perrin said she had a startling revelation: Mr. Nguyen was stealing from the Stolls, writing checks to himself from their accounts and loading their cards with debt. He had some statements sent to his apartment and then made fake statements to leave at theirs.

“It was stupendous and elaborate,” Ms. Perrin said. “He was impressive, the energy he put into all of this.”

One morning in May 2017, she and the Stolls hatched a plan: Ms. Perrin came to the apartment early one morning and instructed the doormen to call the police when Mr. Nguyen arrived. He let himself into the apartment, and a short time later officers knocked. Ms. Perrin began to tell them what she had learned, showing documents from her stacks.

Mr. Nguyen asked the officers if he could bring them a beverage.

“He acted like he was hosting a tea party,” she said. “He was as cool as a cucumber.”

He was arrested that day and ultimately pleaded guilty to grand larceny and other charges. He was ordered to pay more than $300,000 in restitution and served about four months in jail.

Even at the Rikers Island jail complex, Mr. Nguyen made his way into the public discourse. In February 2019, he called WNYC when Mayor Bill de Blasio was on a radio show to complain about conditions there.

“I know it seems like a very privileged thing to do, to go over the head of the administration and call the mayor,” he said.

A month after his release that spring, he wrote a letter to the city’s Correction Department in which he argued against proposed changes to an inmate rule book. At the top of his list, he shared his concern that a new rule that would limit “sexually explicit material” was “overbroad.”

About a year later, he was hired by Saint Ann’s School.

Indispensable and Ubiquitous

Winston Nguyen’s eighth-grade math students and their parents may have been shocked to learn about his criminal past, but it was no secret to the Saint Ann’s officials who had hired him in summer 2020.

A standard background check had revealed Mr. Nguyen’s felony conviction, and at least one Saint Ann’s employee had urged school officials repeatedly against hiring him, according to a person familiar with the process.

He was hired nonetheless, along with several dozen other new employees brought on to accommodate the unusual staffing needs caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Robin Becker, a Saint Ann’s spokeswoman, declined to answer questions. She said school officials were waiting to learn details about Mr. Nguyen once the external investigation was finished. Kenyatte Reid, the head of school, said in a statement that “it would be premature and harmful” to “speculate.”

Mr. Tompkins, the head of school when Mr. Nguyen was hired, said, “Winston Nguyen’s alleged actions are abhorrent and reprehensible, and they contravene the core values of Saint Ann’s School.” He declined to comment otherwise.

Mr. Nguyen was initially the school’s “special assistant for Covid-related projects,” helping with virus-testing protocols and managing the logistics of hybrid learning.

But he quickly emerged as something more, using his low-level job to make himself indispensable — and ubiquitous. As he had in high school, he dressed up most days, now wearing suits with bow ties. He attended school events and after-school sports. He transformed a closet-like space into an office for himself. He was given a key to the building.

By fall 2021, he had so impressed school officials that they wanted to promote him. According to a person who worked at Saint Ann’s, administrators considered making him the assistant to Mr. Tompkins, the head of school, until a senior administrator suggested that Saint Ann’s should not give access to the school’s accounts to someone who had committed financial fraud.

Instead, they made him a middle school math teacher.

It was only a matter of weeks before his Algebra I class searched his name online and found reports about the “scheming home health aide,” as The New York Post put it, who had been “busted for stealing more than $300,000 from an elderly couple.”

Students demanded an explanation. “How could you steal from those old people?” one asked him before walking out of the classroom, upset.

That evening, Mr. Tompkins emailed parents. He insisted that Mr. Nguyen had “proactively disclosed this information about his past” when he was being hired, even before his crime was confirmed by a background check, and that school leaders had “considered the nature of the situation carefully,” including speaking “with individuals who provided strong references.”

The revelation about Mr. Nguyen’s past spread quickly. Some parents were uneasy with his teaching their children. Others suggested that hiring him was a choice to be proud of, evidence of the school practicing restorative justice. But many believed they should have been notified. The faculty was similarly conflicted.

Eventually, the school leaned into his life experience. It added to its slate of seminars a new offering taught by Mr. Nguyen. It was called “Crime and Punishment.”

Many students and faculty members liked Mr. Nguyen, but, as in high school, he was divisive. Some employees said that they grew increasingly uncomfortable with his attempts to cultivate close relationships with his students. At least one teacher expressed concerns to a faculty leader.

Although there were healthy snacks kept in the middle school office, Mr. Nguyen had his own stash for students who spent time in his classroom and office — Oreos, Cheez-Its, Goldfish and Spindrift. He chilled cups in a mini-fridge that students would use to make ice water. He permitted them to hang out in his office without adults.

And he sent wide-reaching email solicitations to students with offers of free summer tutoring that raised eyebrows.

But while the adults worried over old-fashioned emails, the students were enmeshed in their own digital drama.

Beginning in fall 2022 and continuing for a year and a half, a group of students at Saint Ann’s and other private schools in Brooklyn received lewd solicitations on Snapchat from a person who appeared to be a teenager and encouraged them to share naked photos and videos of themselves.

‘Creative Chaos’

The Saint Ann’s community is proud of its unconventional culture that is typified by the school’s hiring practices. But some critics now suggest Saint Ann’s left its students vulnerable.

Founded in 1965 in Brooklyn Heights, the school has marketed itself in part to New York’s wealthy creative class, seeking to educate the children of actors, painters and writers.

Many celebrities (Jean-Michel Basquiat, Zac Posen, Lena Dunham) and children of celebrities (Susan Sarandon and Tim Robbins, Julian Schnabel) have attended.

The school has embraced what it calls a “creative chaos.” Saint Ann’s leaders often hire poets, musicians, playwrights and others possessing a difficult-to-articulate, they-know-it-when-they-see-it, creative spark. In lieu of grades, teachers write long reports about students’ academic achievements.

The school limits parental involvement. A humorous adage suggests parents of Saint Ann’s students “drop them off for kindergarten, pick them up at graduation.”

Parents say they are generally willing to abide, partly because the school has discretion to ask students who administrators believe are not excelling to leave — a fate no Yale-thirsty parent wants to risk. Of the 85 students who graduated in 2024, about 25 percent matriculated to Ivy League universities.

Even as it keeps parents at bay, Saint Ann’s has struggled to manage a cascade of investigations and lawsuits.

In 2023, the school was sued by parents of an eighth-grade student who had attended Saint Ann’s since kindergarten and later exhibited dyslexia and attention deficit disorder. In 2021, he died by suicide three months after learning the school would not allow him to return for ninth grade. (The lawsuit blames school policies for the boy’s death. The school denies what it calls the suit’s “inaccurate and misleading allegations.”)

A few years earlier, an administrator had resigned after hosting students and recent graduates at his home, where they got drunk and smoked marijuana. The school also issued a blistering report in 2019 that documented a history of faculty sexual misconduct from 1970 to 2017.

And in 2020, it gave a job to a man who was about a year out of jail after committing an elaborate fraud.

‘Not Again, Winston!’

Teenagers who are active on Snapchat say that receiving risqué messages from strangers is not unusual.

But among Brooklyn private school students, the number of solicitations to those in similar cliques was enough to get them talking.

On about 10 occasions, prosecutors said, the same Snapchat user had requested that at least seven students (including one who lived out of state) send him photos and videos that included nudity and “sexual performances.” Sometimes he shared the images with other students online. “It is believed that the defendant had similar online interactions with numerous other children,” the district attorney’s office said in a statement.

One video, sent to a student who was about 14, depicted a teenage boy “masturbating on a bed and ejaculating,” according to the criminal complaint.

One student received a provocative image of a girl he recognized, and he reached out to alert her, according to people familiar with what happened. The girl’s parents contacted the Brooklyn district attorney’s office.

While many of the messages came from unfamiliar accounts — @HunterKristoff and @HaircutBongos — some came from an account with a handle that was similar to the name of a Saint Ann’s student.

Saint Ann’s administrators were notified and ultimately determined that the student had no connection to the account bearing an approximation of his name.

But the school did not warn parents that students were being targeted by someone sending and seeking sexually graphic photos and videos. (Later, Mr. Reid, the current head of school, would tell parents that the school was heeding the requests of victims’ and their families who wanted to protect their privacy.)

What administrators were actually focused on, however, was making some staff changes. This March, they told Mr. Nguyen that his contract would not be renewed in the fall because some of his practices as a teacher were not a good fit for Saint Ann’s.

Mr. Nguyen was facing rejection in the broader private school community too.

He had been selected as a volunteer for a three-day New York State Association of Independent Schools evaluation of a private school in Manhattan. He was kicked out after one day, though, when the head of the school raised concerns to association leaders “about how Nguyen had spoken to students during his school visit,” an association spokesman said. (The head of the school declined to comment.)

Back in the secret world of teenagers’ social media feeds, the illicit behavior continued. A widening circle of students began to receive solicitations, parents and former students said.

In May, authorities said, the Snapchat predator increased the stakes, making a payment to a 15-year-old student in exchange for a video of the student “engaged in a sexual performance.”

At that point, the police were closing in.

On June 6, as Saint Ann’s students and parents gathered at the school for an end-of-year chamber music concert and playwriting festival, a large van pulled up near the school, drawing the attention of two students who had slipped outside to grab a snack.

Eight people piled out of the vehicle and grabbed Mr. Nguyen, who was walking down the street, according to the Saint Ann’s Ram, the student newspaper.

“The two students watched as Nguyen was patted down and handcuffed,” the paper reported. “They assumed that he had committed another financial crime, thinking something to the effect of ‘Not again, Winston!’”

But when prosecutors announced the charges, the accusations were nearly unfathomable to school officials and students: The person behind the many lewd requests, the authorities said, was the nattily dressed Saint Ann’s math teacher.

Among 11 felony counts, Mr. Nguyen was charged with using a child in a sexual performance, promoting a sexual performance by a child and disseminating indecent material to a minor.

A Warm Hug

These days, Mr. Nguyen’s comings and goings are recorded by an ankle monitor. He is permitted to leave his apartment for only a few reasons: mostly to attend legal hearings with his lawyer, Frank Rothman.

As Mr. Nguyen, once a can-do employee in sharp suits, awaits his turn before the judge, he reads thick science fiction paperbacks or solves crossword puzzles in pen — dressed in what appears to be the same outfit each time: baggy trousers, an untucked white collared shirt, saggy blazer and black shoes without laces.

The criminal court proceedings in Brooklyn bring Mr. Nguyen back to a familiar neighborhood. The school that once offered a second chance to someone with little professional experience and a criminal record is just a few minutes’ walk away, the two worlds of Mr. Nguyen existing in proximity.

It is this duality — the person friends and colleagues thought Mr. Nguyen was and the reality of what he is now accused of — that continues to bewilder people.

The dissonance was clear after a hearing this fall. Mr. Nguyen huddled with his lawyer at a street corner when suddenly he was greeted with a warm hug from a passer-by.

She was a teacher from Saint Ann’s.

Graham Dickie contributed reporting, and Kitty Bennett and Kirsten Noyes contributed research.

Katherine Rosman covers newsmakers, power players and individuals making an imprint on New York City. More about Katherine Rosman