GUAYAQUIL (ECUADOR)

Los Ángeles Press [Ciudad de México, Mexico]

July 29, 2024

By Rodolfo Soriano-Núñez

After little more than three months, we know why a 51-year-old male decided to end his life in the seventh-floor of the building of the Ecuadoran Congress.

The person who hung himself at the Ecuadoran Congress was a former parliamentary aide, and until then a survivor of clergy sexual abuse.

Suicides as the one at the building of the Ecuadoran Congress are a frequent outcome of sexual abuse, clergy or otherwise.

Back on March 5th, 2024, around 10 am, a maintenance worker at the premises of the Ecuadoran Congress informed their superiors of the corpse of a male hanging at a terrace of the seventh floor of that building.

Little over an hour later, the account of the National Assembly at what used to be Twitter posted a message. The posting provides little or no detail about the circumstances of the suicide of someone identified only as “a lifeless body,” as the statement in Spanish posted after this paragraph shows.

No mention of victim’s name, sex, or any other hint about the possible reasons of the macabre finding. The congressional police and ranking members of the Ecuadoran Legislative branch called later that day a Press conference. A video of that conference appears after this paragraph.

.At the press conference, commander Francisco Zumárraga, head of the congressional police, offered only an additional detail about the corpse: the victim was a male. Later, an Ecuadoran news website added that he was 51 years old.

Over at what used to be Twitter, users took the congressional press release to task. If one goes down the rabbit hole of the comments posted there, one finds the kind of innuendos and conspiracy theories frequent in Latin American politics from Mexico to Chile or Argentina when this kind of tragedies happen.

One user goes as far as to suggest that it could be a trick by President Daniel Noboa Azín to distract the Ecuadoran public opinion as to raise taxes in his country.

Other, uses the suicide as an opportunity to call out the National Assembly as a “criminals’ nest.” A third one raises the question of whether the victim committed suicide or, as it is common to imply in Latin American politics, was forced to commit suicide (“suicided” if one carries a literal translation) by someone else, as to imply that someone was rendering the death as a suicide.

A fourth commentary goes further to insinuate that he was an offering to an Andean First Nations deity, the Pacha Mama, while the lawmakers in the building struck deals to protect drug dealers and criminals, as can the post, appearing immediately after this paragraph, shows.

What happened at the Ecuadoran Congress, or National Assembly, as a strict translation of its official title would be, could have happened at the see of the Mexican House of Representatives, in San Lázaro, Mexico City, or at the Congress of the Argentine Nation at the Callao Avenue in Buenos Aires. The only “difference” would be the names of the subjects and places of this story, where politics meets clergy sexual abuse in Latin America.

As it happens these days all over Latin America, the day Ricardo, an assumed identity, took his live, the Ecuadoran congress was discussing a major reform to the existing laws regarding the sexual abuse of minors.

The image appearing next is a screenshot from the Ecuadoran congress agenda for the first week of March. There one can see how Representative Arturo Ugsha, from the province of Cotopaxi, introduced two days after the suicide of Ricardo, a bill to address sexual abuse in Ecuadoran schools.

Ricardo’s story

Ecuadoran media have been covering the details of how Ricardo, a former employee of the Ecuadoran Congress decided to end his life back in March. Ecuadoran media has provided a detailed account of what happened to him.

A month ago, Wambra, an independent media in the Andean nation, was the first to provide a full account of what happened back in March. They, at the request of the relatives of the victim, named him as Ricardo.

If you read Spanish, please go to their website to get the details of the research done by Sybel Martínez, in a story aptly titled “Sacred impunity”.

Wambra’s account of this case is known to other Latin American and European countries, as it is in Australia, Canada, and the United States. All that is changing in the story is the name of the persons and places involved in the tragic events.

It is the story of a male from a marginalized community in Quito, the capital of Ecuador, who as a teenager found assistance and sexual abuse in the charities set up in that city by the so-called Salesians of St. John Bosco, one of the Roman Catholic Church largest and richest religious “orders.”

So rich, that even Pope Francis has cracked jokes about the riches of the Salesian order. Back in February 6th, 2021, when addressing the leaders of the Focolare lay movement, Francis talked about the “four things that God cannot know”: those things are:

“What the Jesuits think, how much money the Salesians have, how many congregations of nuns there are and, what the members of Focolare Movement are smiling about.”

So large, that the 9,346 Salesian priests and 14,018 male religious worldwide, are second only to the Jesuits with their 10,270 priests and 14,195 male religious.

In Ecuador, there are according to their own data, 131 Salesians males, either priests or religious males, allocated over twenty-three communities, running 115 projects, with twenty-two schools, as the image immediately after shows.

The location of the Salesians work follows the patterns of the Ecuadoran population, as they are heavily concentrated in Quito, the capital city, Guayaquil, its main port in the Pacific coast. They are also in smaller cities as Cuenca and Riobamba, and at three smaller Pacific ports: Machala, Esmeraldas, and Manta, as the map immediately after shows.

Since the late 1970s, the Salesians have had a program to address the homelessness of kids in the metropolitan area of Quito, as this report, dating back to October 1997, proves.

The report deals with the experiences of the Salesian order at the so-called “centers” at Mi Caleta and Residencia Juvenil San Patricio in Quito’s metropolitan area.

San Patricio or Saint Patrick is where Franklin Germán Cadena Puratambi, then a Salesian religious male in his early thirties worked as teacher and where he sexually abused Ricardo when he was a teenager.

The route of a predator

In the coming paragraphs I follow the predator’s path to the priesthood as to understand the key tensions and contradictions shaping the Roman Catholic Church response to clergy sexual abuse in Latin America.

Franklin Cadena was born on January 11th, 1955. Although it was not possible to track down where he was born, through his social media postings it was possible to find that he identifies a small town called Colta as the origin of his family.

He appears in two pictures over one of his Facebook accounts with his relatives at the entrance of the parish in Colta, a town located 170 kilometers, little more than 105 miles, South of Quito, the capital of Ecuador.

He made his first vows as a Salesian brother on January 24th, 1979. Six years later, on January 18th, 1985, when he was already 30 years old, he made the so-called “perpetual” or final vows.

It was the next year when he, as a non-ordained religious male, a so-called “brother” joined the faculty of Saint Patrick in Quito. And it was in 1987 when he attacked Ricardo for the first time.

He remained at Saint Patrick until 1995. That year he asked the then bishop of the diocese of Méndez, Italian born Salesian Pietro Gabrielli to accept him as seminarian.

John Paul II appointed Gabrielli as bishop back in 1993. Two years after his appointment there, he rejected Franklin Cadena’s request. The joint report issued by the diocese of Galápagos and the Salesian order in Ecuador, available in the box immediately after this paragraph, provides no detail as to why bishop Gabrielli denied Cadena’s request.

Joint statement from the Salesians in Ecuador and the diocese of Galápagos on Franklin Cadena’s case. Available as image here.

Were then, back in the 1990s, complaints about his conduct? Who issued said warnings as to prevent bishop Gabrielli in Méndez from accepting Franklin Cadena.

Macas, the see of the bishopric and capital city of the province of Morona Santiago is located 235 kilometers or 146 miles South of Quito, the nation’s capital and 80 kilometers or 50 miles from the border with Peru.

Although the province is key in the territorial disputes between Peru and Ecuador that have caused at least three wars between both countries it is a remote and sparsely populated area, with less than eight inhabitants per square kilometer or less than twenty inhabitants per square mile.

In 1997, Franklin Cadena Puratambi returned to the Salesian communities in Ecuador, although in 1998, he asked for a full dispensation from his vows. He did it after the Apostolic Vicariate or diocese of Galápagos accepted him as a seminarian. It remains unknown if Franklin Cadena tried his luck at other “orders” or dioceses in continental Ecuadoran territory.

De facto?

The report issued by the Salesians and the bishop of Galápagos on June 28th, assumes that Franklin Cadena Puratambi was “de facto” out of the Salesian order since 1994, despite the fact that he kept going back to secure a dispensation for his vows and duties as a Salesian religious male.

The report does not provide details as to the conditions that made it possible for this to happen. In other words, if he was “de facto” out of the Salesian order, why was he not expelled? What prevented the order from deciding about him?

The joint report states that Franklin Cadena sought to be a priest in two dioceses (Méndez and Galápagos), but they do not report whether he tried to be a Salesian priest. Did he? Was he rejected? If so, why? There is no information as to whether other dioceses or religious order rejected Franklin Cadena.

The diocese of Galápagos accepted Cadena Puratambi as seminarian in 1999. There is no information about who presided over Franklin Cadena’s ordination ceremonies, first as deacon and later, on December 6th, 2003, as presbyter or priest. It could be that then bishop Manuel Antonio Valarezo Luzuriaga was the presiding bishop during both ceremonies, but even if not, he had to authorize both ordinations.

Valarezo Luzuriaga, a Franciscan, was responsible as bishop of the archipelago since 1996. Before that date, he and his predecessors led the Catholic Church in the archipelago as priests with the title of “prefect” of the apostolic vicariate since its creation in 1950.

As apostolic vicariates both Méndez and Galápagos are dioceses in isolated regions in Ecuador, entrusted to religious orders. Méndez to the Salesians and Galápagos to the Franciscans. Did Cadena Puratambi attended a Franciscan seminary to complete his formation?

Ricardo made his first report of sexual abuse on April 20th, 2003, when it is possible that Franklin Cadena was already a deacon. Usually, the ordination as deacon occurs between six months and up to a year before the ordination as a presbyter or priest.

The report hides behind formalities to negate any responsibility of the Salesians for Cadena’s ordination as presbyter, which occurred on December 6th, 2003.

It is not clear if the report is accurate when identifying Cadena Puratambi “a parish priest” immediately after his ordination. It seems difficult for any diocese to seamlessly appoint a newly ordained priest as parish priest, even if that priest was already 48 years old.

Contradictions

Moreover, that does not correspond to what Cadena himself published when he was active as a priest and maintained at least three different social media accounts, especially on Facebook. One of them he made private. It was not possible to consult it. Another, which seems to have been the one he used the most in the 2010s, only calls himself a parish priest starting in 2014.

Is the report trying to dismiss or hide any potential responsibility from a superior or supervisor of Cadena Puratambi during the first ten years of his ministry in Galápagos?

Where did he spend his first years as a priest, when newly ordained priests take on positions as vicars or chaplains, under the supervision of a senior cleric?

There is also no precise information about potential incidents in the seminary in the Galapagos, which, in addition, seem unlikely to have occurred in the archipelago. It is hard to believe that a diocese as small as Galápagos could support a major or upper seminary.

Where did he study theology? In one of his social media accounts, as the image immediately after shows, Cadena claims to have studied theology at the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador, the Jesuit university of that country, located in Quito. However, he provides no details as to the dates where he allegedly was there.

What information do the Jesuits of Ecuador have about Cadena Puratambi? Did he try to become a priest with them?

Did Bishop Valarezo Luzuriaga give Cadena Puratambi an exemption on that regard to achieve an easy ordination? Did he do so based on the alleged studies he had done at the Jesuit university at Quito? Did Valarezo Luzuriaga consult the reasons why the Salesians rejected a former member of that order or the reasons why the Méndez vicariate had rejected him?

Did Cadena claim to be a theology graduate at the Jesuit university at Quito? If so, did Valarezo Luzuriaga consult with the Jesuits in charge of PUCE? If he attended a seminary in Ecuador or elsewhere in Latin America or Spain, was there any report from the directors of that seminary about Franklin Cadena’s conduct?

In any case, in November 2019, Cadena admitted his guilt. The diocese of Galapagos “punished” him. It did so with a temporary suspension in “an extended retreat on Floreana Island,” one of the smallest in the Galápagos archipelago, as the map after this paragraph shows.

Around that time, his social media accounts go silent, although it is not possible to be completely sure since he keeps one private.

Hiding behind technicalities

At this point, both the diocese of Galápagos and the Salesians again hide behind a technicality since Cadena Puratambi was not a priest at the time of the abuse against Ricardo.

The joint statement of 2024 identifies Cadena Puratambi as “suspended”. In doing so, it “solves” the issue of the institutional responsibility of the Catholic Church of Ecuador. However, Cadena Puratambi remains a priest. His superiors have not laicized him. And here is where the technicality lies because the repeated sexual attack on Ricardo, back in the 1980s, happened before the diocese of Galápagos ordained him.

In that regard, if there were any change in the vicariate of Galápagos, the new bishop could lift that sanction and reinstate him in his functions as priest.

The signatories of the joint statement exonerate themselves by saying that “there has been no impunity,” when in fact there has been impunity and negligence, since Cadena was a non-ordained religious (a “brother”) when he abused Ricardo at the Saint Patrick’s project in the metropolitan area of Quito in the eighties.

The probability that Ricardo was his only victim during a career as cleric spanning for almost forty years is extremely low, but that is the game that the Catholic hierarchy in Ecuador and throughout Latin America can play because there is no pressure from civil authorities to force them to assume full responsibility for their actions, as the state legislatures in California and New York have done so recently in the United States, as the story linked above proves.

Between Ricardo’s first report to the Salesians in 2003 and the decision of the bishop of Galápagos to suspend Franklin Cadena, almost 21 years passed, with Ricardo’s suicide in between.

Back in June 18th, 2024 a far-right media outlet in Spain published, a story rendering the diocese of Galápagos (available only in Spanish) as affected by problems of clergy discipline associated with one of the far-right’s favorite strawman: gay clergy.

Regrettably, this site, similar in tone and attitude to what Church Militant used to be in the English-speaking Catholic world, insists on portraying the sexual abuse crisis in the Catholic Church as a consequence of the very existence of clerics, predator or otherwise, who are or identify themselves as gay.

The stories Los Ángeles Press publishes in this series assume, instead, that the sexual abuse crisis in the Catholic Church and in other areas of public life is not such because gay people are behind it.

From Alaska to Patagonia

There is a crisis of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church, in other churches such as the Mexican Luz del Mundo (Light of the World), the Latter Day Saints, and in other areas of public life from Alaska in the United States to Patagonia in Argentina or Chile because, whether in the academic, ecclesiastical or government spheres, sexual predators accumulate quotas of power allowing them to remain unpunished.

Just last week, Los Ángeles Press published an account of Abbé Pierre’s case. A hero of the French Resistance during World War II, a champion of the defense of the rights of homeless people and, more generally, of the marginalized, whose main legacy the Emmaus network of charities is active in more than forty countries around the world.

Despite his merits, Abbé Pierre was also a sexual predator who far from attacking homeless young males on the streets of Paris, as could be the situation of Ricardo in Quito in the eighties, attacked women.

In that sense, the myth of the “homosexual clergy” as the culprit for the sexual abuse crisis in the Catholic Church is just that, a myth, which serves well for “media” (or rather propaganda machines) such as Church Militant, to insist on the homophobic obsessions of the extreme right.

Rather than insisting on the idea of the “homosexual clergy” as culprits for the crisis, it is more important to ask how, for example, the diocese of Galápagos and the Salesians of Ecuador are allowed to be unaccountable for Ricardo’s suicide or how are they able to dismiss the very possibility that there are other victims of Franklin Germán Cadena Puratambi who had a clergy career, ordained or not, of almost forty years in the Catholic Church.

It is at this point where one of the new revelations that occurred in France in the last days of July is relevant. According to the French Catholic newspaper La Croix, Abbé Pierre’s family and friends knew of his sexual assaults on women in his care at least since 1957, as the story from La Croix in the image below describes.

Of him, with a career as a cleric of sixty years or so, there are at least seven victims. Is it possible to believe the bishopric of Galapagos and the Salesians of Don Bosco when they assert that Franklin Cadena had only one victim over 40 years?

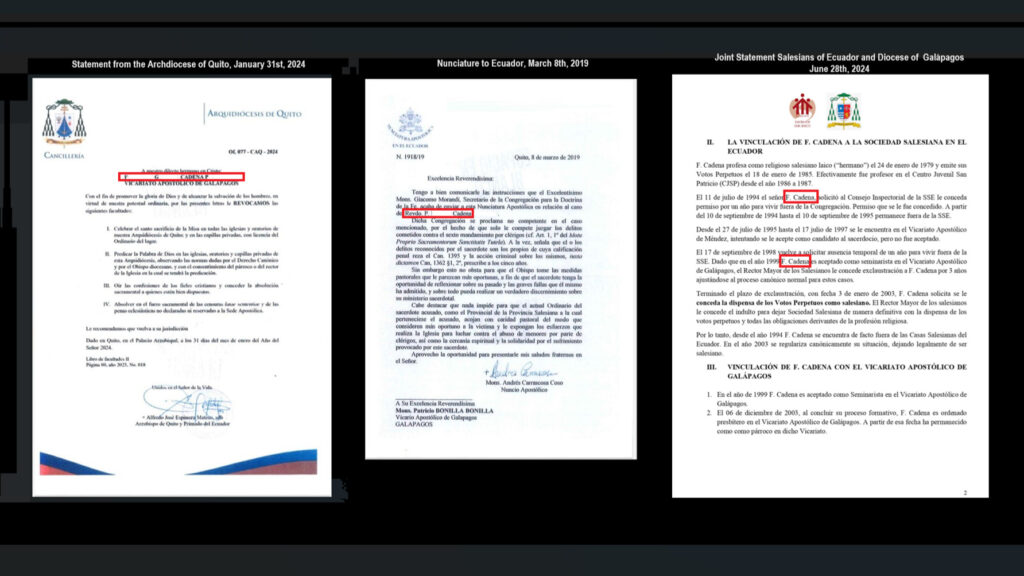

Unfortunately, the secrecy with which the Catholic Church operates, which led them to identify Franklin Germán Cadena Puratambi only as F. G. Cadena P., as the image below shows, makes it more difficult to believe that there is actually any willingness on the side of the Catholic Church to address its own crisis. The image below compiles an announcement made by the Archdiocese of Quito, a letter issued by the nunciature in Ecuador, and a page from the joint statement from the Salesians of Ecuador and the diocese of Galápagos. The three documents censor Cadena Puratambi’s full name.

The Myth and the Flame

Unlike Roman Catholic dioceses in the United States, posting detailed lists of the names and positions held by clerics with credible accusations of sexual abuse, dioceses in countries such as Ecuador, Mexico and Argentina insist in the “nothing to see here” dictum, the very Mexican and Latin American idea of “aquí no pasa nada” (nothing happens here).

The same far-right media outlet already mentioned reports in that piece that the bishop of Galápagos Aúreo Patricio Bonilla expelled one priest and one seminarian because, according to that site, they are in a same sex relationship. The outlet even claims to have fifty photographs that, according to them, prove their relationship.

In doing so, they keep alive both the myth of a potential solution to the clergy sexual abuse crisis without addressing its root causes and the flame of homophobia.

As far as Abbé Pierre’s case, Emmaus is actively addressing the issue. Their leaders are calling potential victims to come forward. They cannot hide behind the homophobia that characterizes media outlets in Spanish and English claiming to be Catholic who believe that solving the clergy sexual abuse requires to magically eradicate gay clergy.

On the other hand, the Ecuadorian episcopate, like others in Latin America and Spain, bets big on formalism both in the interpretation of the Code of Canon Law and in the strategies that its lawyers promote in the civil or criminal courts. Therein lies the tragedy of Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking Catholicism.

It is not only the future of Roman Catholicism what is at stake on this issue. It is also the lives of thousands of victims of sexual abuse, clergy or otherwise, what are at stake.

Victims of sexual abuse are at greater risk of committing suicide due to the long-lasting effects of their experience, the difficulties they face when trying to seek justice, and the never-ending games of powerful institutions as the Catholic and other churches in Latin America and elsewhere.

Although it is hard to offer accurate statistics on the incidence of suicide among victims of sexual abuse, clergy or otherwise, since victims could remain suffering silently for many years, the testimonies gathered by the Australian Royal Commission and by the probe carried in the United Kingdom, show a robust link between clergy sexual abuse and suicide.

For the British Independent Inquiry on Child Sexual Abuse, their findings about the impacts of sexual abuse on victims are available here.

In Australia the very origin of the Royal Commission to investigate sexual abuse in different settings is linked to the stories of an epidemic of suicides in 2012, as this story from Australian news outlet The Age details.