DALLAS (TX)

Wall Street Journal [New York NY]

March 1, 2024

By Shannon Najmabadi and Soma Biswas

Settlement fund could pay hundreds—or hundreds of thousands—for the same abuse

As a Boy Scout victim from Alabama, Gill Gayle is likely to get around $15,000 from a settlement fund compensating child sexual abuse victims, according to estimates.

But if he had been abused in New York, he would be eligible for more than 10 times that amount.

Gayle is one of more than 82,000 men who have submitted claims to a multibillion-dollar settlement fund set up after the Boy Scouts of America filed for bankruptcy amid an onslaught of child sexual abuse cases.

Victims are each entitled to up to $2.7 million from the fund, according to court documents, depending on the severity of the abuse they experienced and other factors.

But the settlement is designed to pay out less to men like Gayle, who grew up in states where their claims would likely be barred because too much time has gone by.

Some say the settlement as structured is generous—offering the men more than they likely would receive had they pursued their claims in state court. But others say it creates a patchwork where men abused in one state receive a fraction of what those in others receive.

Men in more than 30 states will likely have their awards reduced based on local statutes of limitation.

“I don’t care if you were abused in California or Oklahoma or Ohio,” said Timothy Kosnoff, a lawyer who co-represents some 17,000 alleged victims. “Why should the accident of geography determine a person’s compensation?”

Barbara Houser, a former bankruptcy judge who has been appointed to oversee the Boy Scouts settlement funds and process victims’ claims, declined to comment. A spokesperson for the Boy Scouts didn’t return calls.

The Boy Scout settlement has drawn renewed attention to statute-of-limitation laws that determine how long victims or prosecutors have to sue perpetrators. In recent years, some states have adjusted those laws in the wake of high-profile scandals, like sexual abuse within the Catholic Church or USA Gymnastics.

Some lawyers and lawmakers say the different statutes—and different payouts—reflect a core tenet of American governance, where states have different laws on any number of topics.

“How come a woman can get an abortion in California, but her sister in Missouri can’t get an abortion?” said Paul Mones, a Los Angeles-based attorney who has worked on Boy Scout abuse cases for decades. “It’s the exact same issue.”

Others say the size of the Boy Scout settlement highlights the unfairness of the system.

“When you have 82,000 victims and you’re all over the United States, you end up with this scattershot map,” said Marci Hamilton, a University of Pennsylvania professor who founded a nonprofit focused on eliminating statutes of limitation. “Same abuse, two different states. Same defending organization, and completely different compensation.”

Photo caption: More than 82,000 men have submitted claims to the $2.4 billion settlement fund.

Some lawmakers are trying to change their statutes of limitation to help Boy Scout victims. The settlement administrators say they will take into consideration new legislation. Lawmakers in Alabama, Indiana and other states are considering bills to do so now.

The Boy Scouts filed for bankruptcy four years ago amid a wave of sex abuse lawsuits and mounting expenses settling those cases.

After hard-fought negotiations, the Boy Scouts, insurers and its local councils agreed to fund a $2.4 billion settlement in return for winning legal releases shielding them from further lawsuits over past abuses. Attorneys representing thousands of Boy Scout victims agreed to the settlement’s terms, including the statute-of-limitation provision.

While former Boy Scouts with the strongest claims could get up to $2.7 million under the terms of the settlement, victims’ lawyers say the amount will likely be a fraction of that because there isn’t enough money in the fund. The size of the payouts could change based on the final number of claims and continuing litigation with insurers.

Statutes of limitation exist for good reason, say some who don’t support their expansion. Memories fade as time goes on and evidence often disappears, leaving those accused unable to adequately defend themselves, they say.

Opening windows to sue for crimes alleged to have happened in the past can be particularly problematic.

“You can’t save records that you threw out. You can’t revive people who are dead who might be witnesses,” said Cary Silverman, an attorney for the American Tort Reform Association, which isn’t involved with the Boy Scout settlement.

Advocates for expanding the windows of time in which to sue say most young people aren’t prepared to confront an abuser until well into adulthood. The average man who experiences sexual abuse as a child comes forward around age 50, according to researchers.

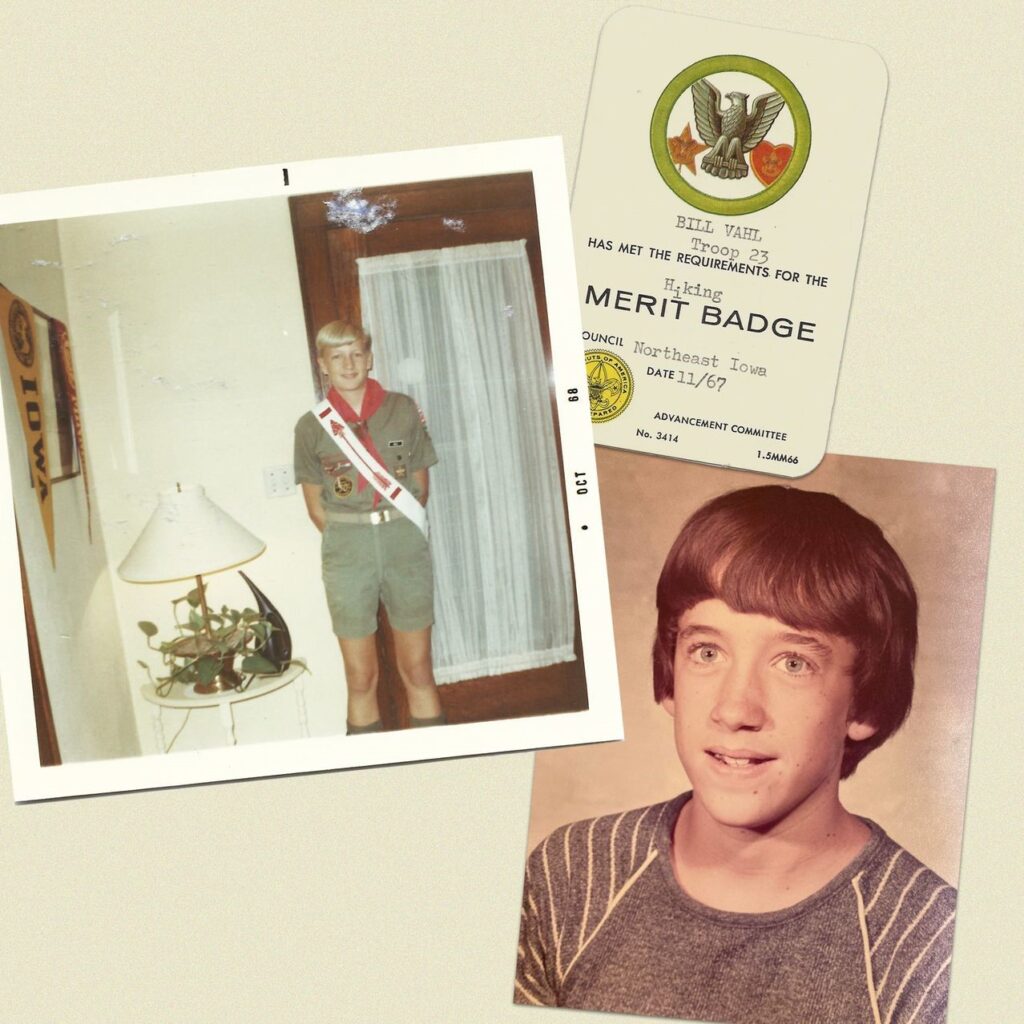

“What 18-year-old that you know would have the wherewithal and the strength…to walk into a police station or a lawyer’s office or to their parents and say, ‘Hey, this guy made me give him oral sex, and I did it,’” said William Vahl, 71 years old, who was a Boy Scout in the late 1960s.

Michael Foust, 63, said two memories of the abuse he said he experienced growing up in Crawfordsville, Ind., are etched into his mind: how it started and how it ended. He was 11, lying in bed next to his scoutmaster at a campout, when he felt the man’s finger pulling down his underwear in the back, he said. The rest is a blur, he said.

“I remember whispering, he kept whispering to me,” he told Indiana lawmakers in February, growing emotional. “I cannot remember a single thing he said but he whispered the whole time in my ear.”

Foust and his parents filed a complaint about the man and he was arrested. But as Foust kept recounting the details of his alleged abuse, he began to fall apart, he said. When Foust’s parents learned their son would have to testify in court, they decided not to pursue charges, he said.

Foust is hopeful Indiana lawmakers will pass a law extending the civil statute of limitations for former Boy Scouts.

“I was abused in Indiana,” he said. “That wasn’t my choice.”

Write to Shannon Najmabadi at shannon.najmabadi@wsj.com and Soma Biswas at soma.biswas@wsj.com