CHICAGO (IL)

Chicago Sun-Times [Chicago IL]

March 1, 2024

By Robert Herguth

The Servites order has had numerous priests and brothers accused of sexual abuse and faces an onslaught of new lawsuits. But, unlike many dioceses and orders, the group has no public list of members deemed to have been credibly accused of sexual abuse. And other church lists are incomplete.

Key findings

- The Order of Friar Servants of Mary, commonly known as the Servites, has its U.S. headquarters in Chicago, but it maintains no public list of credibly accused members despite calls for transparency.

- One church watchdog group counts 11 Servites accused of child sex abuse over the years, and the order has been accused of covering up for some offenders.

- Ther are at least nine pending lawsuits against the Servites stemming from alleged abuse by a former Chicago priest who allegedly molested numerous children in California years ago.

- A California law that temporarily lifted the statute of limitations on child sex abuse claims has flooded the courts there, and the impact is being felt in Chicago.

- Public lists of credibly accused clergy maintained by the Archdiocese of Chicago and the Diocese of Rockford omit as many as four Servites.

When St. Philip High School on the West Side was closed in 1970, one of its longtime priests, the Rev. Kevin Fitzpatrick, had to find a new place to teach. He ended up at Servite High School in Anaheim, California, which, like St. Philip, was run by the Order of Friar Servants of Mary, a Catholic religious order known as the Servites.

As he had done at St. Philip, Fitzpatrick taught math and coached swimming. There have been no known accusations of sexual abuse while he worked and ministered in Chicago, but he has since been accused of molesting numerous children at the suburban Los Angeles school — sometimes under the guise of giving them haircuts in a barber’s chair he kept there.

“It happened so many times that it all sort of clouded together,” says a man who says he was molested repeatedly during the four years he attended Servite High School in the late 1970s and early 1980s. “Father Fitz ruined my f—— life, and I was lucky that I got it back on my own.”

The accuser is one of at least nine men who have sued the Servites and related church organizations in the past few years, accusing Fitzpatrick of having molested them while they were attending the Anaheim school.

The priest left the school in the early 1990s.

Though the accusations date so far back, the current lawsuits were allowed by a “look back” law in California that took effect in 2020, temporarily lifting the statute of limitations to sue over long-ago child sex abuse accusations.

That extended legal window has rocked the Catholic church in California, leading the Archdiocese of San Francisco to seek bankruptcy protection in August amid more than 500 new claims.

The California law’s effects also are being felt in Chicago, not only because clergy that once served in the Chicago area are among those being named in California cases.

Servites’ U.S. headquarters are in Chicago

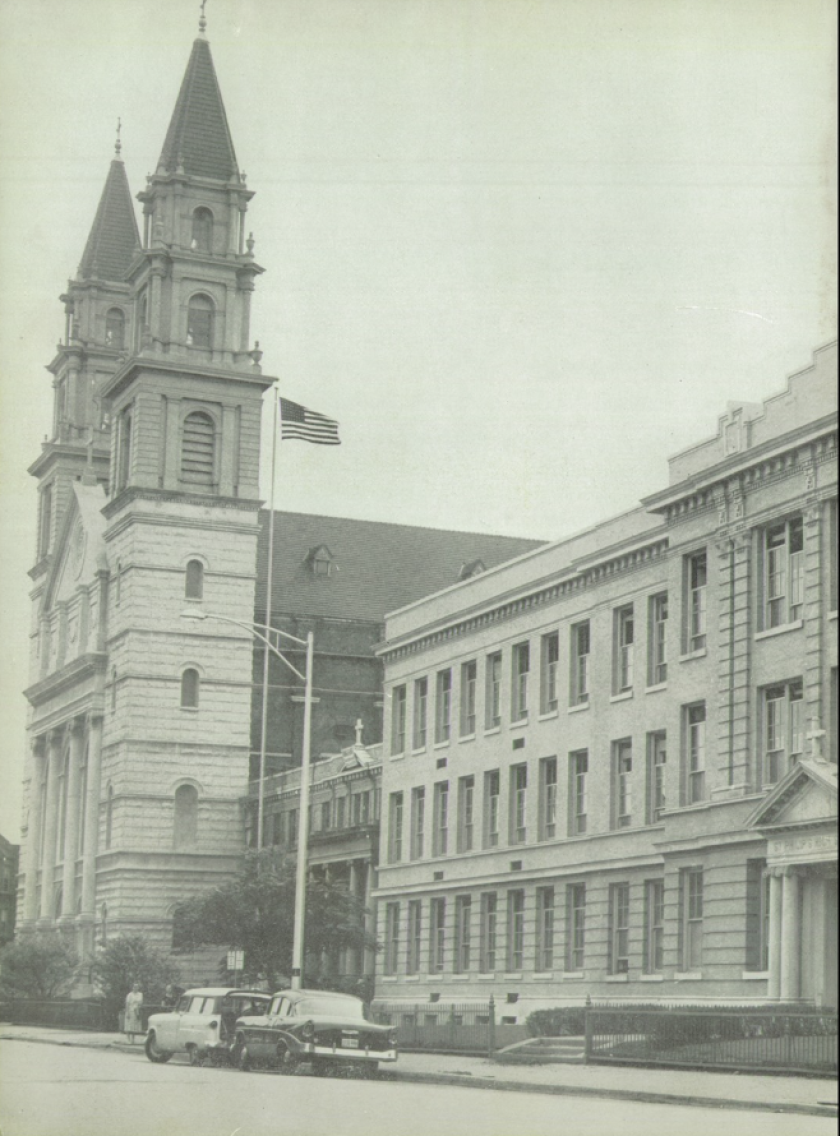

Servite leaders defending the wave of litigation are based in Chicago. The group’s U.S. headquarters are in the same complex that used to house St. Philip and also is home to the historic Our Lady of Sorrows Basilica at 3121 W. Jackson Blvd.

Amid the new lawsuits, Servite leaders might be faced with deciding whether the order can sustain potentially large financial judgments, settlements and other legal costs.

Mike Reck, an attorney for some of Fitzpatrick’s accusers, says he thinks it’s “a distinct possibility” that the Servites might consider seeking bankruptcy court protection.

The Rev. Eugene Smith, who oversees the Servites’ U.S. province, couldn’t be reached for comment. Attorneys for Burke, Warren, MacKay & Serritella, P.C., the Chicago law firm defending some of the current lawsuits, won’t comment. For years, the Archdiocese of Chicago has turned to the same firm to handle abuse complaints.

Several former St. Philip students who knew Fitzpatrick say they never heard of any improper behavior by the priest while they were attending the West Side school.

“It’s very sad,” says a onetime student who was a member of the swim and water polo teams at St. Philip. “It’s kind of shocking.”

The Servites are fighting the lawsuits and have not publicly deemed the accusations to be credible, though, after the first of them became known, Servite High School pulled Fitzpatrick’s name from its new aquatic center and removed a bust of him. School officials won’t comment about those actions.

Cardinal Blase Cupich, the leader of the Chicago archdiocese, has called on religious orders that operate in his jurisdiction of Cook and Lake counties to be transparent about any accusations of sex abuse by their members. That mirrors requests from many victims and church reformers, who say that posting public church lists naming clergy members deemed to be sexual offenders is a step toward healing as well as an acknowledgment of past abuses and coverups amid a decades-old abuse scandal in the Catholic church.

Servites mired in secrecy

But the Servites appear to have remained mired in secrecy, with some of the accusers involved in the lawsuits saying the order knew of sexual abuse by Fitzpatrick and did nothing about it.

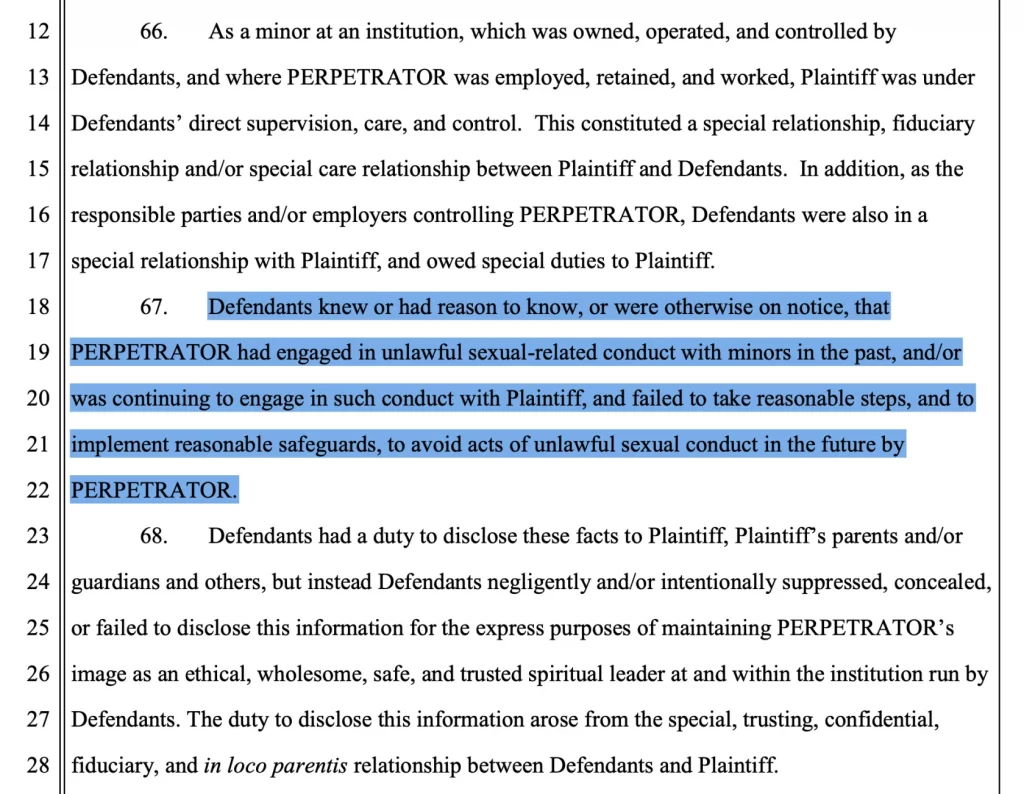

A lawsuit accusing Fitzpatrick of molesting a Servite High School student in the early 1980s starting when the boy was 14 says: “Defendants knew or had reason to know, or were otherwise on notice, that perpetrator had engaged in unlawful sexual-related conduct with minors in the past, and/or was continuing to engage in such conduct with plaintiff and failed to take reasonable steps and to implement reasonable safeguards to avoid acts of unlawful sexual conduct in the future by perpetrator.”

Another accuser — the individual who attended Servite High School in the late 1970s and early 1980s — says in an interview that another Servite once walked in when Fitzpatrick was assaulting him.

Whether anything was reported by that other Servite clergy member isn’t clear.

Fitzpatrick remained at the school for years after that and continued to molest other students, according to the accusations in court records.

Reck says the abuse by Fitzpatrick was repeated and horrific, “anything from grinding on them when he’s cutting their hair to the most invasive stuff you can think of.” The order’s refusal to produce a “full history and whereabouts of sexual offenders creates a public safety nightmare,” he says.

The Servites’ U.S. province maintains no public list of credibly accused members. Church officials won’t say why.

Their website includes a page titled “Safe Environment” that details the Servites’ stated commitment to preventing and dealing with child sexual abuse, but it doesn’t list names of known abusers, as many dioceses and religious orders operating in the Chicago area do.

The Servites’ U.S. web page has a phone number to which accusations of sexual abuse can be reported. No one answered the line during numerous calls from a reporter, and messages weren’t returned.

A list maintained by a nonprofit church watchdog Bishop Accountability includes 11 Servite priests and religious brothers accused of molesting children in the United States. Among them is Fitzpatrick, who died in 1997.

The Rome-based international headquarters for the order — which was founded in the 1200s and has a special devotion to Jesus’ mother Mary — has roughly 800 friars around the world, down from about 2,000 in 1965, when a Chicago priest was elected its global leader.

Servites overseas accused of abuse

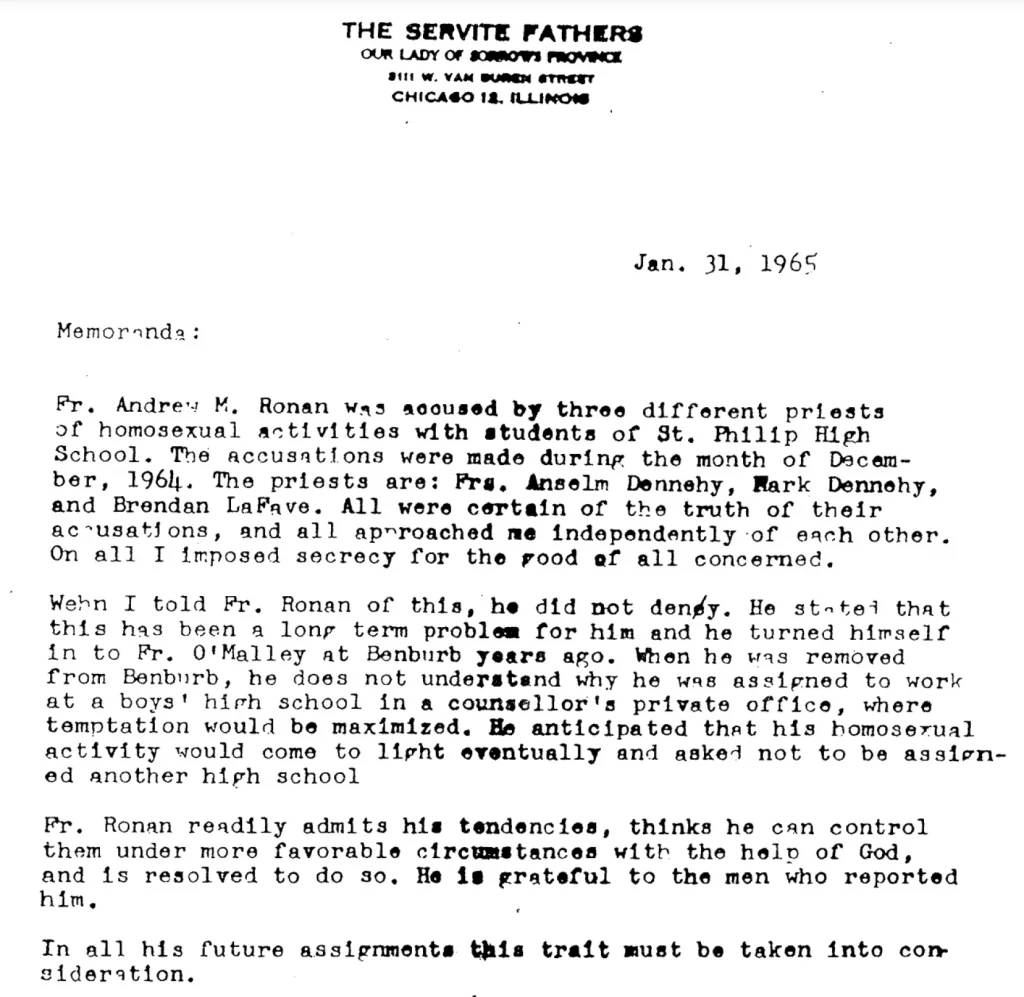

Servite clergy members overseas have been accused of abuse, including a member of the order in Northern Ireland, the Rev. Andrew Ronan, who was from Chicago and who admitted sexually abusing a student in the 1950s. Ronan was sent back to Chicago, where he was then assigned to St. Philip and molested several other boys, church and court records show.

A religious superior wrote about Ronan in 1963, “I am certain he can never be trusted.”

But the order allowed him to continue ministering. While serving in Oregon, he abused again before leaving the priesthood in 1966, records show.

Ronan died in the early 1990s. Chicago’s Servite province established the order’s presence in Northern Ireland in the 1940s and did so in the 1950s in Australia.

Neither of those ecclesiastical jurisdictions abroad maintains a public listing of credibly accused clergy.

The Chicago Sun-Times found that other Servites who were accused of having abused children elsewhere fell under the oversight of the order’s Chicago leaders. Brother Gregory Atherton, a deceased Servite who is named on the Archdiocese of Los Angeles list of offenders, made his final vows with the order at the West Side basilica in 1954, records show.

“Chicago is the hub and spoke of the whole deal,” says Patrick Wall, a former Benedictine monk who works for Jeff Anderson & Associates, a law firm that’s handling lawsuits against the order in California.

The online public listing maintained by Cupich’s office includes two Servite priests deemed to have been credibly accused of sexual abuse, including Ronan.

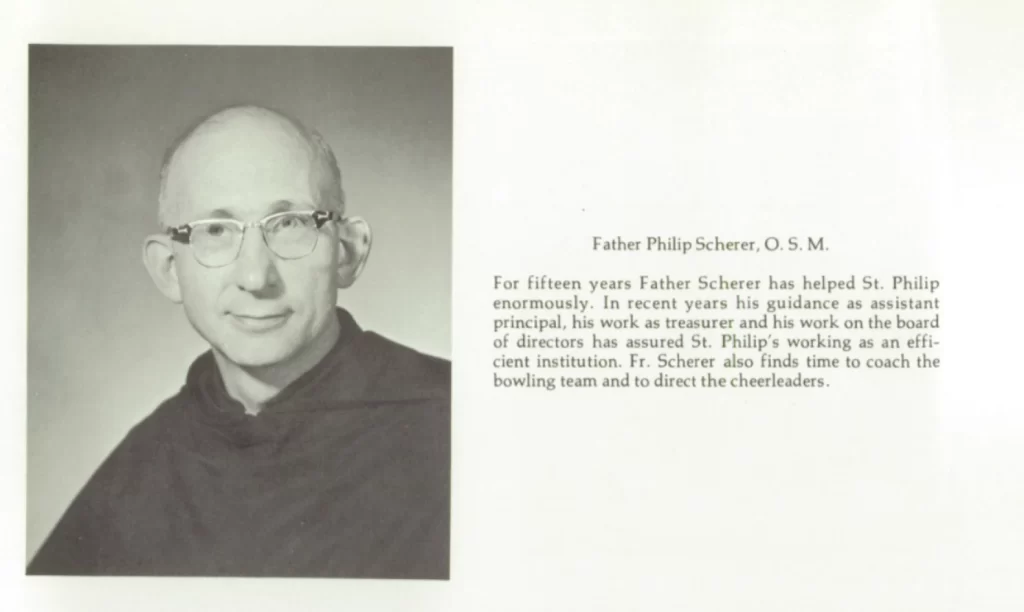

The other is the Rev. Philip Scherer, who, while at St. Philip, taught mechanical drawing, served as assistant principal and coached the bowling team. He died in 2016 at 95 and is buried along with more than 120 of his brethren in a section of Queen of Heaven Cemetery in Hillside dedicated to the Servites.

Who’s not on Cupich’s list of abusers

Cupich’s list doesn’t include Fitzpatrick or three other accused Servites.

Cupich for years declined to include on the archdiocese’s list any members of religious orders who served in Chicago and were found to be abusers, instead including only diocesan priests, those who reported directly to him or his predecessors.

Cupich backed away from that stance in late 2022, as Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul was preparing to release a report that documented continued church secrecy regarding sexual abuse by Catholic clergy members in Chicago and the suburbs.

Until then, Cupich had encouraged orders to create their own lists, saying those groups knew best which members to include. Other dioceses, including Milwaukee’s, continue to take such a position.

But even with some order priests now included in Cupich’s list, the Sun-Times has found others who aren’t listed there despite church findings that they were abusers, including one who had been part of the Augustinian order, the Rev. John Murphy.

Cupich’s aides have declined to say why Murphy isn’t listed. And they won’t say whether they knew of four Servites who were deemed to have been credibly accused of abuses who aren’t on their list.

One of those four is the Rev. Mark Santo, who served at a now-closed parish near the Chicago Housing Authority’s former Cabrini-Green public housing development on the Near North Side and was involved in anti-drug efforts in the area in the 1960s and 1970s, according to church records and published reports. He also served at the order’s now-closed seminary in Hillside and at St. Philip, church records show.

Santo, who died in 2008, is on the list maintained by the Diocese of Springfield-Cape Girardeau in Missouri as having been among clergy members who served in that area and were found to have been credibly accused of abuses.

A spokeswoman for the Missouri diocese says it “did an internal audit of all clergy files” in 2018 and 2019.

In those years, many church organizations embraced transparency over child sex abuse amid a new wave of the abuse scandal in the Catholic church that prompted outrage among many of the faithful. That outrage was spurred largely by a Pennsylvania grand jury report revealing the breadth of the scandal in that state, and accusations that then-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick had sexually abused boys and young men for years.

“As part of that review, we reached out to all religious congregations around the country in 2019 in order to confirm those religious order priests that we had record of ever having served here, their dates of service and whether or not an allegation had ever been made against said religious order priests,” the Missouri diocese spokeswoman says.

She says representatives of the diocese spoke at that time with the Rev. John Fontana, who then was a leader of the Servites’ U.S. province and is now based at Assumption Catholic Church, a parish staffed by the Servites not far from the Merchandise Mart in the Loop.

It’s unclear what Santo was accused of doing.

Fontana didn’t respond to calls or emails.

Santo ministered at a parish in Ironton, Missouri, from 1964 to 1966, according to the Missouri diocese. He also served in the Archdiocese of Milwaukee but isn’t on its public list of abusers, records show.

Also not on the Chicago archdiocese list is John Huels, a longtime Servite priest who once ran the order’s province in Chicago and attended and appears to have taught at the Catholic Theological Union on the South Side, a graduate school governed by two dozen male religious orders, including the Servites. Huels was accused in the 1990s of abusing a boy in the 1970s on the East Coast. The accuser, who lives in Chicago, became a Servite as an adult but left the order after going public against Huels, according to published accounts.

Until a few years ago, Huels was teaching at a Catholic university in Canada, in the Archdiocese of Ottawa, which doesn’t maintain a public list of clergy found to have been credibly accused of abuses. Huels, who continued to publish scholarly religious articles, couldn’t be reached for comment.

The Rev. Donald Duplessis, who has been on the Archdiocese of Los Angeles list for years as a result of sexual misconduct accusations from 1968 to 1970, isn’t on the Archdiocese of Chicago list, though the church’s own records show he lived in 2003 and 2004 at the Servite monastery attached to the West Side basilica and next door to the old St. Philip.

Through a lease with the Servites, the former high school has been occupied for more than 20 years by the Alain Locke Charter School, whose leaders say they didn’t know an accused child predator might have been living next door.

“The buildings we rent are physically separate from the rest of the Servites’ property, and our students are supervised by our school staff at all times,” the school’s board chairperson says.

Duplessis, who died in 2018, taught freshman Latin at Servite High School in Anaheim in the late 1960s and served as student activities director. He recently was accused in a California lawsuit of molesting a boy decades ago, court records show.

Duplessis previously was based at a now-defunct Servite seminary near St. Charles, church records show. While at the seminary, which is in the Diocese of Rockford, he was accused of acting inappropriately with students, sources say.

Duplessis isn’t on the Rockford diocese’s public list. A spokeswoman for the diocese, which includes Kane and McHenry counties, says, “We have no record, no notification, no indication that the person in question served or studied there or that he has been accused.”