(AUSTRALIA)

News Corp Australia [Sydney, New South Wales, Australia]

September 25, 2023

By Shannon Molloy

Patricia Jones was snatched from her mother when she was five and subjected to years of brutal abuse – an experience that haunts her decades later.

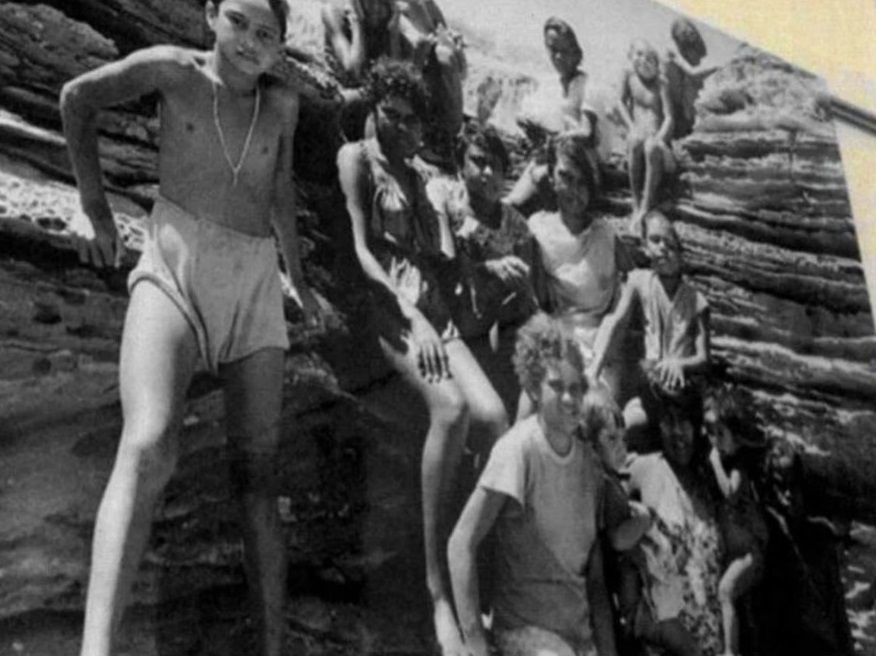

[Photo above: Ms. Patricia Jones, now 73, still has nightmares about her horrific childhood. Picture: Supplied]

Almost seven decades on, Patricia Jones still has nightmares about the cohort of brutal nuns who physically abused her as a child.

In the dead of night, the long-dead Sisters of St John of God grabbed at her, dragging her from slumber and depriving her of peace.

Nightmares are common for the 73-year-old, who requires medication to help cope with the lifelong trauma resulting from the eight painful years she spent at Holy Child Orphanage in Broome, Western Australia.

It wasn’t really an orphanage. Ms Jones and most of the other 100 Aboriginal girls effectively imprisoned there had families of their own.

They had been snatched from their loving mothers by police and welfare officers, empowered by the Native Welfare Protection Act, to become part of what is now known as The Stolen Generation.

Ms Jones was five when she was taken. She doesn’t recall much of her life before Holy Child, except for how it felt.

“I remember feeling safe and secure and loved,” she told news.com.au. “That’s what I remember.”

A childhood of brutality

Those feelings of safety and security quickly became foreign as Ms Jones and the other girls were subjected to the wrath of the nuns, who dished out barbaric punishments for the most minor of offences.

When she was nine, one of the sisters, an angry woman called Winifred, flew into a rage when she couldn’t tell the time from a clock on the wall.

The nun grabbed her tiny hand and put it into an open desk, before slamming the lid shut on her fingers.

She was then dragged outside by her hair, where the woman repeatedly punched and kicked her helpless body. The priest, Father Nicholas, had to drag Sister Winifred off her.

“They were so cruel. We were just little kids. The nuns didn’t hold back and seemed to enjoy disciplining us for anything they could think of.

“We’d be deprived of food as punishment a lot of the time. Although, a meal was usually pretty basic – sometimes onion soup, which was just raw onion in hot water.

“One day, a few of us were sent to the home of a pearl farmer’s wife in town to clean up her garden. When we were done, she gave us a penny each. As kids, we were thrilled.

“We went to the shop and bought chocolates. When we got back, we were all given a good flogging – made to lift up our skirts and bend over so the nun could whack us with a bamboo stick.

“That’s just one of many examples. It was a horrible place.”

One day, Ms Jones was sent to Broome Hospital with a nasty bout of tonsillitis and spent a night in the ward.

“I was in a room with four beds and in one was this old lady with white hair, who looked very sick with tubes coming out of her,” Ms Jones recalled.

“One of the nurses came over and told me that the woman was my mum. She said, ‘Do you want to come over and meet her?’ I was very shy. I think I was shocked and didn’t know what to do. I just stood there.

“So, my last memory of my mum is seeing tears stream down her cheeks as she looked at me. I was discharged and sent back to Holy Child, and the day after that she died.”

That sight of her dying mother is one of many that haunt her.

Although, in a way, she feels like one of the lucky ones. So many of the girls she was with at Holy Child never found their mothers again.

“To this day, in their 70s, they have never been able to find their mothers.”

Lifelong trauma and pain

At 13, Ms Jones was sent to Perth to a Catholic high school where she completed her studies and went on to become a nurse.

She remembers being “quite naive” about the world and not understanding the extent of her mistreatment.

Around the age of 18, three words kept swirling around her head: “Do you understand?”

Their significance became apparent when she had a stark and painful memory of the day, aged five, she and her sister stood in front of a magistrate in Broome to be declared wards of the state.

“I didn’t know what was going on. It was just me and my sister in this courtroom with the judge and a policeman beside us. The magistrate looked at us and said: ‘Do you understand?’ My sister nodded and then lowered her head. I just smiled at him. I thought it was OK.

“At 18, it hit me what it all meant and I became a very angry person for a very long time. I was so angry about what happened to me.”

Ms Jones devoted the rest of her life to Aboriginal welfare and development, as well as advocating for Indigenous rights.

Her extraordinary career saw her work in senior management roles for the Department of Health and Aboriginal Health Services in WA. She was also a ministerial staffer in Victoria. For a time she was the Aboriginal Employment and Training Office for the Commonwealth.

“I represented the Territory in many national forms, such as the Aboriginal Health Standing Committee.

“I travelled overseas a few times for Foreign Affairs … to Kenya, Zimbabwe and South Africa. I went to Dili when it became a nation to develop an economic strategy for their new government.

“The final five years of my career, I worked in oil and gas in Perth as a consulting developing strategies for Indigenous employment and training opportunities.”

She believes her success stems from a determination to “not give in” to what happened to her, although pain and trauma have always been present in her life.

Calls for change

Ms Jones is supporting a submission by law firm Slater and Gordon to the WA government to extend legislation enabling historic sexual abuse claims to include those who suffered physical abuse.

The firm’s WA Abuse legal counsel Abigail Davies said the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in 2018 led to sweeping changes across Australia.

“Each of the states and territories enacted legislation that enabled adults who had suffered child sexual abuse and were still psychologically injured to seek justice in the courts,” Ms Davies said.

“We know that many people abused as children take decades to disclose what happened to them, so it was an important reform.”

However, the changes did not extend to those still suffering the impacts of historic physical abuse in institutions. For many victims, it means they feel left out.

“What we’re saying now is that physical abuse should be included. We should build on those reforms so physical abuse can bring an action to seek justice in the courts.

“The Royal Commission’s terms of reference was limited to sexual abuse, so we’re not criticising. But we know that the experience of people in institutions and other settings who were physically abused can endure similar life-long psychiatric injuries.”

For many people, being heard and acknowledged by a court is an important part of the healing process, Ms Davies said.

“It keeps them in a kind of limbo to not be part of that process. They know what happened to them was wrong. I think this change would have an enormous impact on a number of people. I think it will offer some kind of relief.”

Later in her life, Ms Jones obtained some records relating to her time at Holy Child.

Among them was a report card from grade five, in which a nun had noted with disdain: “The trouble with her is she’s very defiant”.

“As I got older, I came to think of it as a badge of honour,” she said.