LA PAZ (BOLIVIA)

El País [Madrid, Spain]

May 5, 2023

By Julio Núñez

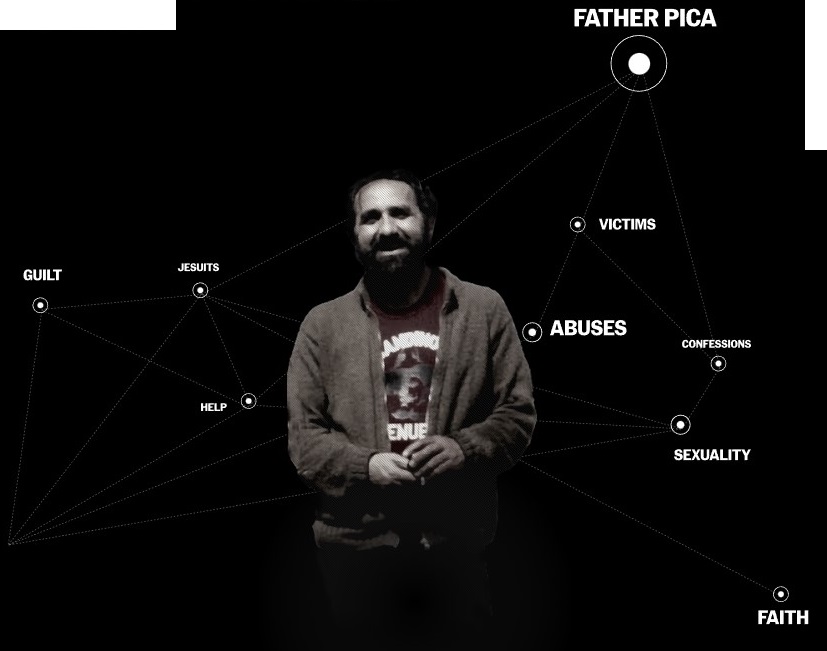

A Spanish member of the religious order of the Society of Jesus (known as the Jesuits) sexually abused dozens of children in Bolivia. The church covered it up, but when he died, Alfonso Pedrajas left behind a shocking confession. EL PAÍS reconstructed his story, in his own words and those of the victims and people who knew him

[In the copy of this article cached for preservation, quotations from the diary are in bold italics. Quotations from interviews with victims are bulleted in bold italics. Several footnotes are in italics, marked with an asterisk, and refer to the bolded name in the previous paragraph. Words highlighted in yellow are illustrated by the following photograph and/or caption.]

During what would be their last trip, in late August 2009, the Spanish Jesuit priest Alfonso Pedrajas, 62, made his boyfriend promise something: “Whatever it takes, you need to get my computer. I don’t want anyone else to have it.” His partner swore that he would, as they drove their gray Toyota down the dusty roads that lead to the Urmiri spa and resort in western Bolivia, where the couple was headed on vacation.

“That was what he told me,” his former boyfriend said 14 years later, speaking with El PAÍS by telephone from Bolivia. “I had no idea what he meant by ‘whatever it takes.’ Did he mean I’d have to convince someone to give it to me? Would I have to steal it? I really had no idea,” says the man — Pedrajas’ partner for the last four years of his life — who was afraid to have his name published for this story.

“But did you know — before you saw what was on that computer — that Alfonso had sexually assaulted dozens of minors, and that the Jesuits covered up the complaints?”

“Yes,” he says, sighing in dismay, “he told me about his concerns, his fears. But he also told me that the church as an institution supported him.”

A few weeks later, on September 5, the priest died of cancer in a hospital in Cochabamba, Bolivia. When his boyfriend arrived for the funeral, a brother who had travelled from Spain had already collected the Jesuit’s belongings: photos, books and a guitar. He gave Alfonso’s partner the ACER computer, because he figured that it was a very personal object.

Back at home, the Jesuit’s boyfriend turned on the computer. He was the only one who knew the password. He browsed through the files and found a document that two years earlier Alfonso had hinted he was writing. The document, called Historia (“Story”), was a kind of memoir: 383 computer-typed pages, filled with reflections, accounts of various episodes in Alfonso’s life, and a few dozen letters. All told, 350 entries with bold-typed headings indicating the place and date where he wrote them. Like a map charting a long and sinuous road, the priest’s diary follows his life from 1960, the year when he entered the Jesuit order as a novice, to 2008, the year he stopped writing after succumbing to exhaustion and illness.

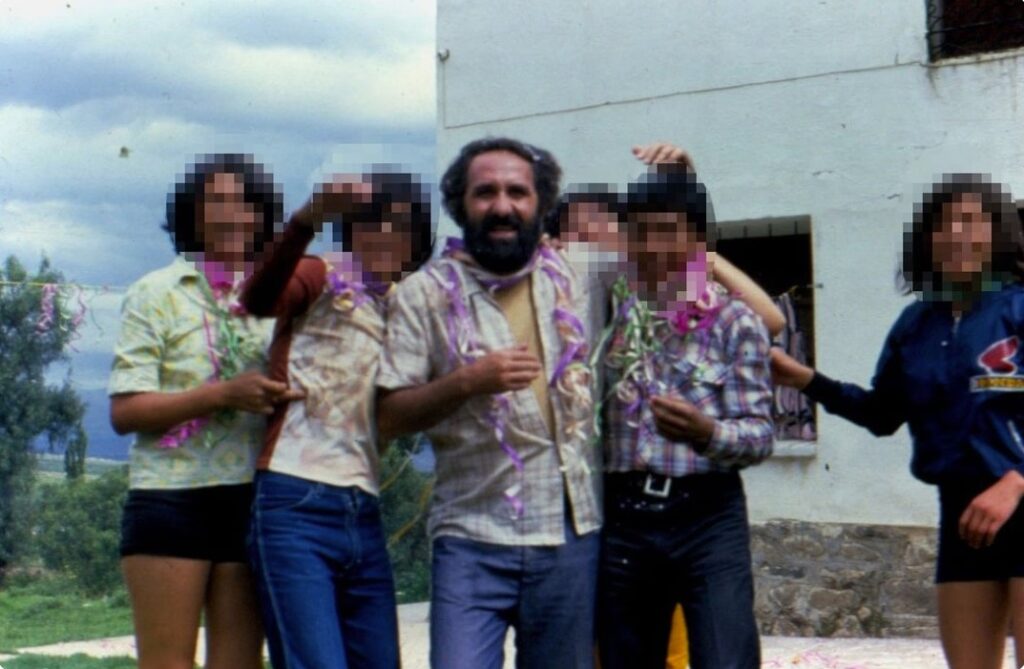

[Photo caption: Jesuit priest Alfonso Pedrajas, also known as Padre Pica, during one of his visits to the Urmiri resort in Bolivia, a few years before his death.]

For the first time since EL PAÍS began its sweeping investigation into child sexual abuse in the Spanish Catholic Church in 2018, the newspaper has gained access to a document — Pedrajas’ diary — that recounts abuses and their cover-up from the other side: from the perspective of the perpetrator.

In his diary, the priest admits to abusing dozens of children while he was a teacher in several religious schools in Latin America, most notably during his time as the director of a private boys’ college in Cochabamba. He also recounts how the Jesuit order, including at least seven provincial superiors and a dozen Bolivian and Spanish clergymen, covered up his crimes, along with the complaints of several victims. Pedrajas writes in his diary that he is afraid of being found out and blackmailed. He is ashamed of his crimes, but always refers to them as “sins,” “mistakes,” or an “illness.” He confuses consensual homosexual relations with assaults on minors. He admits to abuses that he never describes in detail, but that his victims, five of whom spoke with EL PAÍS for this story, look back on in horror.

As he read the diary, the priest’s partner saw the confessions right before him, in black and white. Confessions like: “My biggest personal failure: without a doubt, the pederasty.”

Without thinking about the consequences, he sent Pedrajas’ brother a DVD by Courier Express containing dozens of photographs, along with the Jesuit’s memoirs. “I never thought it would end up in the press,” he says. Someone in the family printed the contents of the DVD, kept it in a green ring binder, and put it in a cardboard box. And that is where it stayed, forgotten in an attic in Madrid.

Until one day in December 2021, when Fernando Pedrajas, the priest’s nephew, was cleaning out the attic and came across the secret diary, covered in a thin layer of dust. Fernando glanced at it fleetingly, and took it home to read. “The first pages were beautiful,” he says. “Some were letters to my grandmother, where he told her enthusiastically about how he wanted to become a good priest. But as I read on, I realized the reality: my uncle was a pedophile.” Fernando read in horror his uncle’s estimate of the number of children he abused:

“I hurt so many people (85?). Too many.”

Fernando knew that he was dealing with something much bigger than just an isolated case of child sexual abuse in the church. He decided to report everything he had found to the Society of Jesus in Bolivia. “The victims come first. The most important thing is that they find some kind of justice,” he says.

During the summer of 2022, Fernando maintained a brief email correspondence with the current director of the school in Cochabamba where his uncle committed most of his abuses, but the director refused to take any responsibility. Alfonso’s nephew presented the diary to Spanish prosecutors, who dismissed the case for exceeding the statute of limitations. Finally, Fernando reported his uncle’s abuse to former Jesuit Provincial Superior Osvaldo Chirveches, now in charge of investigating abuses within the religious order. Since he filed the complaint in October, Fernando has yet to receive a response on the status of the church’s investigation. The only communication he has received from Chirveches has been a persistent: “Send us the diary.”

Chirveches insists that the order has only received one complaint, and that the church has opened a preliminary canonical investigation into the matter. He has not said whether or not the order was already aware of these abuses, nor has he questioned the provincial superiors who, according to Pedrajas’ memoirs, helped cover up the crimes. “Since we don’t have the diary, we can’t expand this investigation ex officio,” he argues.

Faced with the possibility that the church would bury the case, Fernando decided to contact the press, and turned Alfonso’s diary over to EL PAÍS, which has conducted its own investigation into the case, studying the priest’s memoirs and uncovering additional photographs and other documents that contextualize his confessional account. EL PAÍS contacted several Jesuit officials who allegedly helped cover up Pedrajas’ crimes, and spoke to five of his victims — various others are mentioned in the diary — who recounted what the priest dared not detail on paper: how he abused them, and the traumatic afterlives of that abuse. The following account is structured around fragments, in loose and non-chronological order, from the diary of Father Alfonso Pedrajas.

This is where the story begins:

PART 1.

“I’m not that guilty”

If I joined the Society, came to the Americas and professed my perpetual vows, it was to be a saint. Lima [Peru], March 2, 1963

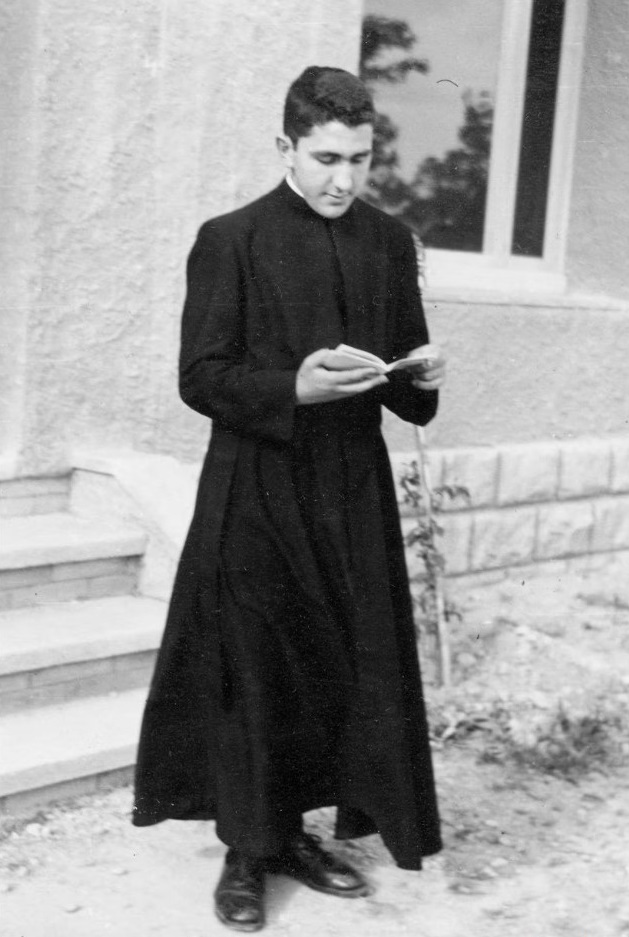

Alfonso Pedrajas Moreno was born on June 10, 1943, in Valencia, Spain, into an extremely religious family. At the eager age of 17, he traveled to Raimat, in the northeastern region of Catalonia, to join the Society of Jesus as a novice. Only a few months after entering the order, and convinced that he was destined by God to be a Jesuit priest, he wrote his parents to tell them the news that would forever change his life: he was leaving for Latin America to become a missionary.

Alfonso describes this new calling as inspired by a desire to help the poorest of the poor. During his first decade in Latin America, between 1961 and 1971, he lived between various Jesuit centers in Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador. This period of his life was dedicated to his religious training, and was when he first began teaching. In Bolivia, he taught at Colegio San Calixto, at Colegio Nacional Ayacucho, and at the juvenile center Correccional de Menores, all three located in the city of La Paz, Bolivia. He also taught at Colegio Colombia, in Lima, Peru, and the San Antonio Abad Seminary, in Quito, Ecuador. It was during those years that the young Jesuit, then in his twenties, wrote about his first sexual assault, in a neighborhood in Lima.

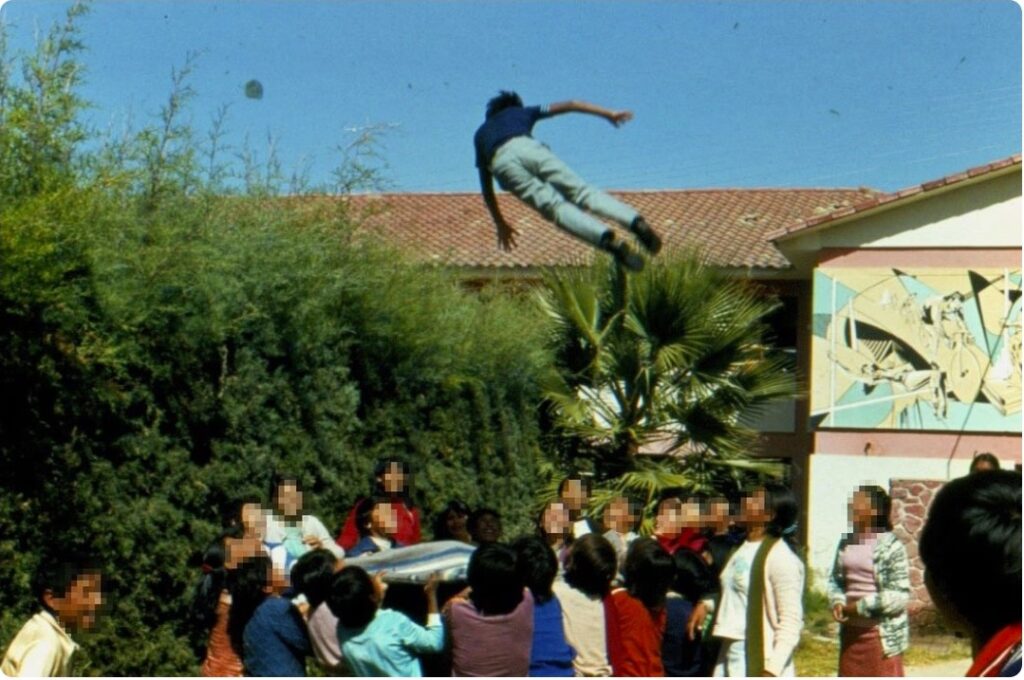

[Photo caption: Father Alfonso Pedrajas (left), also known as Padre Pica, during his time as a teacher at San Calixto school in La Paz, Bolivia.]

I was still in Miraflores when I made my first mistake. I remember it as a fierce struggle, with a crucifix in my hand — the great failure of my life. Lima [Peru], April, 1964

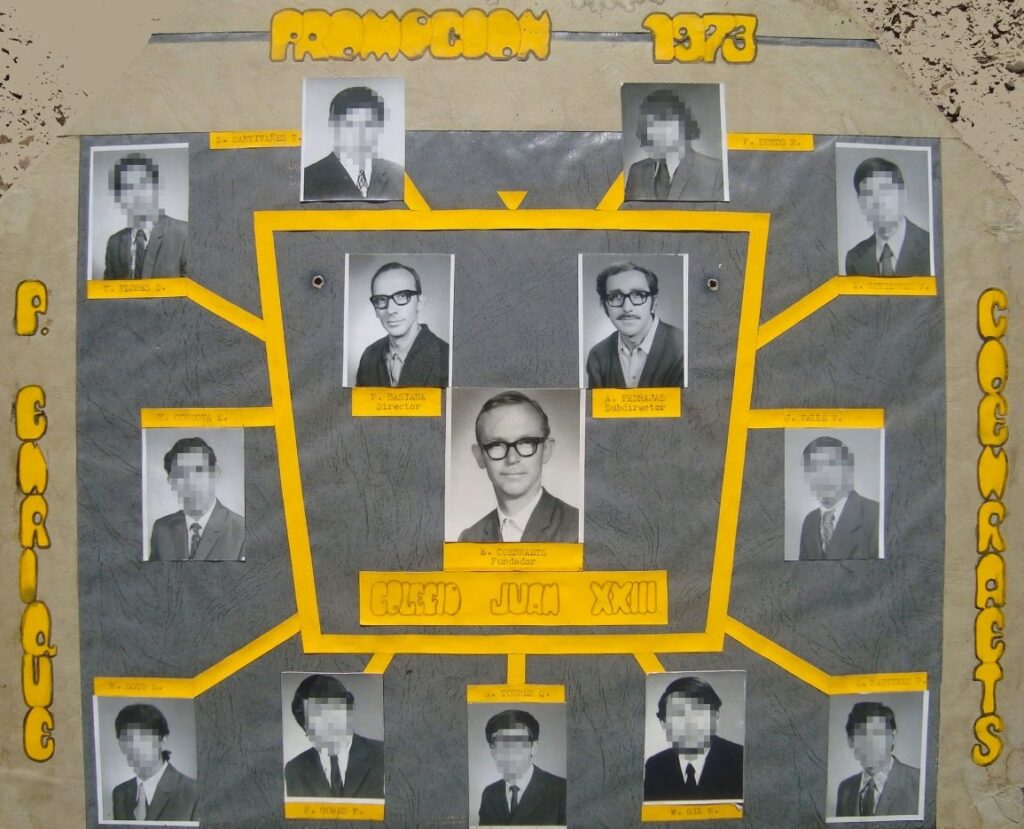

Following this period of religious training, and six years after his first known abuse, Alfonso, who by then was going by the nickname Pica, or Padre Pica, finally settled in Bolivia. In October 1971, the Society of Jesus appointed him deputy principal of Colegio Juan XXIII, a boarding school that at the time was dedicated to taking children out of poverty and giving them the possibility of a brighter future. Padre Pica was one of the Jesuits at the school in charge of traveling around Bolivia to find children to recruit into the program.

Three years after his arrival, Pica was promoted to principal and began transforming the school into a kind of sovereign state. The older students would work half the day so that the center could be self-sufficient: they had a bakery, pigs, cows, a vegetable garden. Students manufactured manhole covers that they would then sell to the local town government.

They called themselves Little New Bolivia, and Padre Pica was the ultimate sovereign power. The priest ran the center and orchestrated the lives of hundreds of young boys. Today, many former students, who had been born into poor families, post fond remembrances on social media, looking back on those days with nostalgia.

[Photo caption: Upperclassmen at Colegio Juan XXIII in Cochabamba, Bolivia, feeding and caring for animals.]

Others — the priest’s victims — look back in horror.

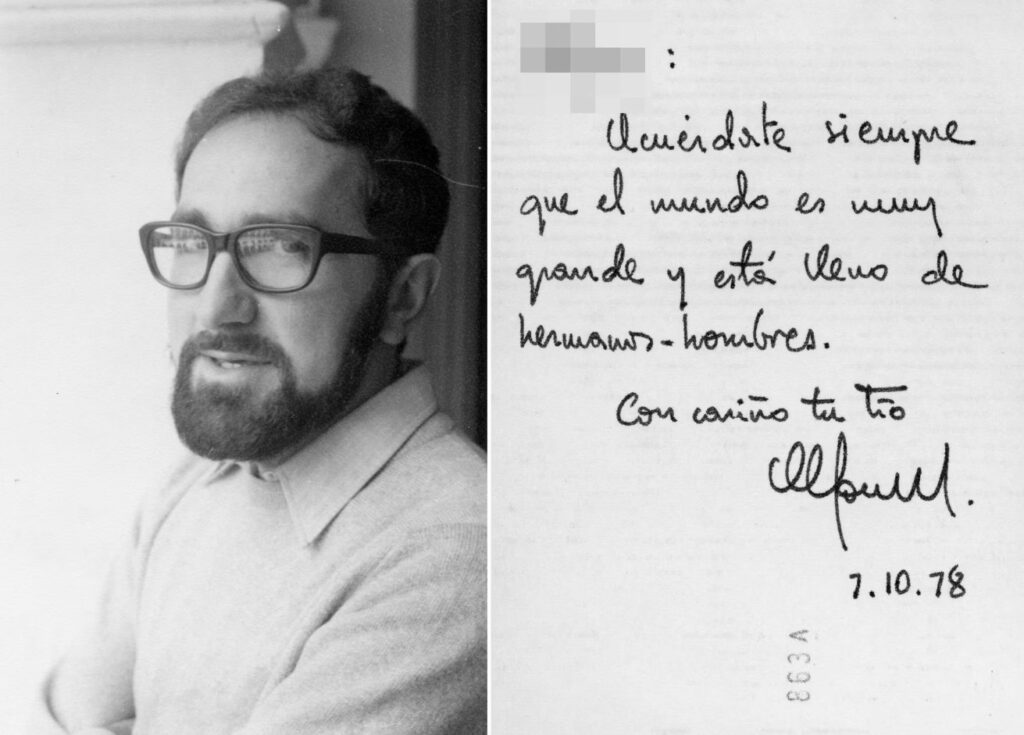

An account of these past 17 years: failure, shame, hypocrisy, pettiness, total disorientation. I feel so small. I have done so many bad things. I beg to be reborn: if I return, let it be anew. I see everything clearly: my emptiness, a distant God in hiding… I am not so guilty. Caracas [Venezuela], June 21, 1978

Padre Pica traveled to Spain in 1978 for his third profession of vows — the final stage in a Jesuit’s religious formation. There, at a Jesuit center in Alcalá de Henares, a city northeast of Madrid, Pedrajas confessed his sexual abuses to the late priest José Arroyo, his instructor and the man who a few years earlier had prepared Jorge Bergoglio, now Pope Francis, for the same exam.

There is no record in Pica’s diary of the conversations he had with Father Arroyo, but Pica does write about his instructor’s opinions and recommendations on the matter, and in his account, strips the assaults of their moral dimension. In Pica’s telling, Arroyo advises him not to mention the abuses in his confessions, and not to consider giving up teaching. At no point does he advise Pedrajas to stop abusing minors. Some of Pica’s notes on his conversations with his superior: “I shouldn’t feel like a repentant sinner,” “nothing is going to happen to me,” “[these are] isolated cases.”

Pica passed the ecclesiastical examination and returned to Cochabamba to teach. Despite his confession, he was neither investigated nor suspended. Back in Bolivia, he continued to abuse his students.

Pedro Pérez (a pseudonym) was one of them.

The victim, now 58 years old, spoke with EL PAÍS over video call. He says the poverty in his early years was so extreme that it was nearly impossible for him to imagine a future in which he would not be constantly hungry. But everything changed one rainy afternoon, when a small bus took him to Colegio Juan XXIII. “It was wonderful: comfortable dormitories, splendid dining rooms, soccer fields,” he remembers. “And the food was excellent. Imagine going from a family that had nothing to a place where all your meals were guaranteed.” His first year there was a happy one.

[Photo caption: Photograph taken by Padre Pica of a group of his students, some of whom were his victims.]

Until the night the fear found him. As usual, Padre Pica turned off the lights at 10.30 p.m., started up his record player, and played the soothing sounds of Mercedes Sosa, Violeta Parra or Quilipayún over the school’s loudspeakers.

[Photo of dormitory with audio.]

As the vinyl spun in the darkness, Pedro felt Pica’s footsteps as the priest walked across the large communal dormitory, visiting the bunks of some of the boys. With the music playing in the background, Pérez eventually fell asleep. And then his turn came:

- “I woke up, and he was touching my genitals. I was 15 years old. I was frozen, petrified. He was telling me, in a low voice, ‘Relax, don’t worry.’ It was terrible.

Pica came back for another round. The second time was more “fierce.”

- “He masturbated me. I couldn’t defend myself. And while he was masturbating me, he was saying: ‘Who do you like? Imagine touching her tits, her ass.’ I ejaculated and I remember he even cleaned me up and then I fell asleep.”

After that night, the boy began to notice comments that he had ignored until then. One morning, in the school bathrooms, a friend of his stormed in, flustered and full of rage. Perez asked him:

— Hey, brother, what’s wrong?

— That son of a bitch El Chapa [Pica] came to poke at me last night.

Perez knew what he meant. Before long, that student left the center. But Pérez could not afford “that luxury.” He had to put up with the priest’s molestations if he wanted to have a plate of food and any hope of a future. “For me, leaving Juan XXIII meant going back to being poor,” he says.

A year later, at the end of 1982, Pérez graduated into one of the upper classes, where the dormitories were private and Pica could not freely come and go. He thought this meant he could live in peace. But then one night, after dinner, a female classmate came to the dining hall, upset and shouting. “Pica is looking for you,” she said. “He’s waiting for you in his bedroom. He’s very sick and says that only you can help him.”

Pérez went up to the priest’s room. He says that he found Pica there, lying on his bed, “out of his mind.” He asked Perez to lie down next to him, and when the boy did as he was told, in an instant, the priest pounced on him, restraining Pérez as he undressed him. Pérez says he still remembers Pica’s unpleasant smell. He forced the boy to lie face down on his stomach.

- “He pulled out his penis and forced me to turn around. I resisted, but he was stronger. He didn’t penetrate me, he just rubbed his penis over me, but sometimes I think my mind might be trying to trick me.”

After a while, the priest released him, got dressed, and Pérez left the room in shame.

[Photo caption: An undated photograph of Padre Pica delivering a speech on the veranda of Colegio Juan XXIII.]

Around the same time that Pica was sexually assaulting Pérez, Roberto Peña, a 12-year-old student at the school, was trying to convene several companions to petition the priest’s Jesuit superior for help. It was the boys’ first act of organized resistance against the abuse. Pica got wind of the plan, and called Peña to his office. Inside, Peña recalls, the priest warned him: “I found out what you’ve been talking about. I told you not to tell anyone about those things. You know that if you go through with your plan, next year you won’t be coming back to school.”

In the case of this student, “those things” that Pica wanted him to stay quiet about had started happening at the beginning of that year.

It was a Saturday morning. Peña was in the school library and one of his molars began to ache. A classmate advised him to go to the infirmary, which Pica himself ran. When Peña entered, he saw a stretcher in the middle and, next to it, a small record player was playing classical music.

“Come in. Lie down here. Take off your shoes and your jacket, you’ll be more comfortable,” he recalls the clergyman telling him in a paternalistic tone. Pica did not want to give him medication, but rather to give him a relaxing head massage so that the pain would disappear.

- “When I was dozing off, I felt someone touching me down there. First on my belt, then on my fly… I didn’t know whether to open or close my eyes. I felt his mouth and his beard [on my intimate parts]. Then I felt a mouth on mine and I started to gag. Then a phallus in my mouth and I started to vomit,” Peña describes. The priest tried to reassure him with a phrase that he still remembers: “God wills it.”

This student also began to notice Pica’s nocturnal wanderings among the beds in the dormitory. On one of those nights, Father Pica led him to his room, which was small and had an unpleasant smell.

- “He caressed me and performed oral sex on me. He tried to get me to do it to him, but I couldn’t. He also tried to penetrate me. In the end he ended up sitting on top of me, and I masturbated him. He came on my chest and on my face,” Peña recalls.

The last time was before the school vacation. The pedophile told him to climb on the back of a red motorcycle and took him to Taquiña, a retreat house about eight kilometers from the school. There, this victim recounts, the Jesuit stripped him naked and tied him to a bed, hand and foot.

- “He began to whip me with a belt.”

Peña says he began to cry and the Jesuit let him go.

Pica left the school in 1983, a few months after threatening Peña with dismissal if the boy told anyone what he was doing with the students.

Today, it all started. The farewell to the school was a cold affair. […] I have left them all behind. Oruro [Bolivia], January 14, 1983

The Jesuit order sent Pica to work as a laborer in the mines of Oruro, in western Bolivia, near Lake Uru Uru. “He wrote me a letter from there, blaming me for being sent to the mines because he thought I had told them everything,” Peña remembers. “But I didn’t do it, I didn’t tell them. I don’t know who it could have been.”

The story Pica told his students, says one former schoolboy, was that he went to the mines “to feel in his soul what the Bolivian miner, who is so exploited, feels.”

[Photo caption: Pica during a trip to Madrid in 1983.]

Manuel López (a pseudonym) arrived at the school the same year that Pica went to work in the mines. By then, his classmates were commenting about the famous Padre Pica who molested children. López says that, at the time, he didn’t pay any attention to the warnings.

A year later, in 1984, the priest left the mines of Oruro and returned to Colegio Juan XXIII. One day, López stopped Pica in one of the school’s corridors to ask for help.

- “Trusting him completely, I told him I had pain in my penis. Later, I learned it was phimosis. He just told me to go to his room.”

When he entered Pica’s room, the priest pulled down his pants and began performing fellatio on him.

- “I knew that wasn’t going to cure me, and I just pushed his head away. I asked him what the church would say about it.”

The boy was also a victim of Pica’s nighttime dormitory visits. One night, he woke up and caught the priest touching his genitals:

- “He put his index finger to his lips and said in a low voice: ‘Shhhhh, here’s your aspirin for your headache’ but I hadn’t asked for anything.”

The next day, he got up the courage to go to Pica’s office to reprimand the priest for what he had done:

— What you’re doing is disgusting. What everyone says is true: you’re a faggot.

—Who says that?

—Everyone.

López says the priest defended himself, arguing that he did things with men because, since he was a priest, he was prohibited from doing anything with women. Then, López remembers, he just changed the subject and started talking to him about photography.

[Photo caption: Students at Colegio Juan XXIII studying in one of the school’s classrooms.]

- “The aftershocks of the abuse have been devastating to my emotional, economic and work life.”

Pica stopped abusing him, but he claims that years later, in 1986, a classmate tried to rape him during a party.

- “He was panting desperately and saying he wanted to do to me what Pica had done to him. I knew that it had been worse for him than it had been for me.”

That student’s name is also mentioned in Pica’s diary.

All told, at least a dozen victims have contacted each other to talk about what happened and to denounce their cases and seek justice. “Many lives have been shattered,” one former student says. “Padre Pica had a lot of positive attributes and he did a lot of good work. But what he did to those hundreds of children erases all that good work.”

Pica writes that, during his final period as the school principal, between 1984 and 1989, he confessed his “sins” to other priests. Along with his notes in the diary, he included evaluations from his superiors pertaining to his possible promotion to the position of provincial superior. All of them emphasized his dedication to the poor, but also noted his faults: “He is manipulative” and has “certain philias and phobias (that he has not yet completely mastered),” they wrote. None of the priests mentioned that he abused minors.

In the midst of that sadness, I wanted to fight to overcome my problems, but I had less and less strength, and the snowball was just getting bigger. Taquiña [Bolivia], March 22, 1989

Pica left Colegio Juan XXIII in 1989 to assume responsibility over the Jesuit novices in Cochabamba and Oruro. During those years, the priest began to write more about the abuses he had committed. In the diary, he uses initials to indicate sexual relations he had “without consent.” And, for the first time, he acknowledges that his past has been coming to haunt him.

PART 2.

“I dreamed that they found me out”

I dreamed last night that they found me out and I left Bolivia. Oruro [Bolivia], January 6, 1994

Father Alfonso Pedrajas asks God to help him put an end to his abuses: “Help me,” he writes. “Don’t let me hurt anyone else. Not one more of your children.” Pica’s need to tell everything, to confess it all despite the “shame” he feels, is clear. “I have been a degenerate (or a sick man who is trapped?).”

In his diary, Pica outlines in detail his plan for confessing everything to a friend, the Catalan Jesuit Marcos Recolons. He uses key words and phrases to refer both to the crimes of pederasty and to his homosexuality: “Religious repression,” “F. without consent,” “I didn’t think there would be consequences,” “isolated cases,” “the great question: is it a sin?”

EL PAÍS contacted Recolons as he was preparing take a trip to visit the indigenous communities of Bolivia’s Sécure River, to ask him about his meeting with Pica.

Recolons would only say that his relationship with the priest was that of a spiritual companion. All of his conversations with Pica, he says, are protected by the seal of confessional secrecy: “I can say absolutely nothing. I am very sorry.”

This was not the last time Pica would ask a religious authority for advice on how to deal with his predicament. The priest spent the spring of 1997 in Valencia, Spain, and on several occasions took the opportunity to meet with a psychologist, the Salesian priest Ángel Tomás García, to whom he confessed everything. Pica’s memoirs include comments about these sessions, and about Tomás García’s psychological assessment, emphasizing the consequences that Tomás had warned him there would be if he continued abusing minors, and the strategies he should pursue to avoid continuing the behavior: “See the dignity of these defenseless people. Someday they will feel used, manipulated,” “cut it off at the root,” “avoid feelings of, and fixations on, guilt.”

*Tomás passed away in 2007, in the community of San Antonio Abad in Valencia. There is no record of whether he reported the pedophile Jesuit to the Police, as required by the penal code. This religious, in addition to creating an office of psycho-pedagogical orientation in several Valencian Salesian centers, was superior of the order between 2000 and 2006.

The psychologist insisted that Pica should not confuse crime with sin, and that “the most important thing is not the sexual issue [homosexuality and pedophilia], but the need for tenderness and affection.” Tomás recommended that Pica focus on distinguishing between abuse and consensual sexual relations, and that he undergo periodic evaluations.

The visit to the psychologist was a frightening wake-up call for Pica, and convinced him that he needed to stop abusing children, mostly out of fear of being discovered and punished. “My little flock, never again!” he wrote in 1998.

The law would be harsh on me (jail, banishment, expulsion). The weight of all my mistakes is crushing me. Yes, I am guilty. Before Him, I have no words. My silence is shame, it is guilt, it is pure misery. […]. I have caused suffering; I have caused harm. Chuquiñapi [Bolivia], February 21, 1998

That same year, Pica was removed from his position as instructor of novices, and was appointed “person responsible for guiding new initiates to the Society of Jesus.” He tried to put his fears out of his mind, but found it impossible. “I am rotten,” he writes.

In his diary, Pica constantly reiterates the advice he received from church members to whom he turned for help. One note stands out: “Don’t gamble with luck!” That same year, 1999, a prominent figure begins to appears in his diary: the Jesuit Luis Tó González, another pedophile transferred to Latin America by order from Spain, after being convicted of child sexual abuse — a story this newspaper revealed in 2019.

*Luis Tó was part of the cloister of the San Ignacio school in Barcelona. At the beginning of the nineties, the Provincial Court of Barcelona sentenced him to two years in prison for abuse. Without a record, he did not go to jail and the order transferred him to Bolivia. It was 1992.

In his memoirs, Pica writes that the two knew each other. He recounts how, in the Bolivian city of Copacabana, in 1999, Luis Tó was the only person to congratulate him during a presentation Pica delivered to the city’s religious community on a book he had recently published. He mentions Tó several times in his diary, and while he never notes anything about the priest’s past as a convicted child molester, he notes that most of the other Jesuits in Bolivia are uncomfortable with his presence in the country.

The start of the new millennium is the most convulsive and troubling period for Pica, who fills nearly half of the pages of his diary with comments from that time. This is when the first denunciations from his victims begin to arrive.

I’m tired, so tired, but I think I need to write, even if I don’t feel like it. Mom called me this afternoon. She told me very simply: ‘They called from Belgium, they were asking for you, ‘Is Pica there?’ etc. She gave him my phone number in La Paz. Before hanging up, the stranger (about 35 years old, mom said) told her: he raped my son. La Paz [Bolivia], January 15, 2001

Days later, Pica writes that his brother called to warn him that a former student had once again called the priest’s parents at their home in Valencia, telling them that their son, the Jesuit priest, had raped him when he was a young boy. Pica descries the fear taking hold of him: “I’m trembling, terrified that he will blackmail me with something very serious. Or worse: that the whole world will find out.”

The priest is in La Paz. He is in such a state of anxiety that for three days straight, he has been taking Ansietil, a benzodiazepine sedative, to calm his nerves. His hope, he writes, is that it will all end in a “friendly visit,” but he worries his victim will take advantage of the occasion to “get money out of him.”

PART 3.

“I have told it so many times…”

I’m demoralized, defeated, a failure. Honestly, I don’t feel like changing, because I don’t feel like doing anything. La Paz [Bolivia], January 28, 2001

On several occasions, the Jesuit priest turned to his superiors and friends in the church for counsel. Pica writes in his diary that he confided in his provincial superior, Ramón Alaix, confessing his need “to be received,” and admitting: “This need to be loved, for years it has led me to seek affection where it was not appropriate. And now, like a hangover, I am left with a recurrent problem.”

Among the list of people the priest turned to was Óscar Uzín, a prestigious theologian, now deceased. Pica felt comfortable with him. He describes him as a clergyman with “a full gay life” who “has stopped believing in God.” Uzin treats Pica well, and does not judge him. He only advises him, “without acting shocked,” not to abuse minors.

But Pica’s fears would prove much greater still, when, on March 21, 2002, during a trip to Valencia, he came across an article published in EL PAÍS: “The priest who abused 130 children.” It was a full-page story, first reported by The Boston Globe, about the child sexual abuse scandal rocking the Catholic Church. For Pica, it came as a major shock. “I am stuck between two walls (the past and the present) and they are closing in on me, crushing me,” he writes.

This situation continued to haunt him for months:

What consumes me now are the pedophiles on TV and in the press. I have spent moments filled with tremendous anxiety. It affected everything: my sleep, work, relationships, addiction, everything. I am anxious. I am afraid. Tomorrow I’ll talk to Ramón at 8:30 in the morning. I am going to propose that he take me to Valencia, to ‘take care of’ mom. I have to escape from this anguish and mediocrity. La Paz [Bolivia], June 17, 2002

Two months later, Pica would return to Valencia for a longer stay. In his diary, he does not explain the reasons for his trip. Far from Bolivia, the Jesuit writes that he finally feels “the haunting fear of los juanchos [this is how Pica refers to the former students of Juan XXIII]” beginning to recede.

He even mentions one of his victims, noting that the case of abuse no longer torments him. “I think I have the ability, now, to live with that weight in my pack,” he writes.

Pica begins travelling around Spain, performing various spiritual duties in cities across the country. Along the way, he reflects in writing on his daily life. In one of the diary entries, he describes how much he was impacted by, and felt himself represented in, The Crime of Padre Amaro, a film about a Mexican priest who has sex with a young girl and then forces her to have an abortion.

Pica asks himself: “And what if they made a movie of my life?”

Pica’s internal struggles are depicted through the dozens of notes and diagrams in his diary, in which he scrutinizes his thoughts and sets goals for himself: “Do not harm any of the little ones.” He writes that last sentence sitting in a train car, on his way to Huesca, a city in northeast Spain. There, he would meet a young bishop who many years later would become the president of the Spanish Episcopal Conference: Cardinal Juan José Omella.

“On one of our days in Huesca, we were accompanied by the bishop of Barbastro (because Huesca is temporarily a vacant seat), a man named Juan José, dressed all in black, but a warm and decent person. He invited me to confess, and we had the opportunity to talk in a relaxed way about many things (in my style of talking, full of questions). The bishops are mainly concerned about more or less regional issues: successions, the [Episcopal] Conference, the government, religion classes, financing… but not so much, I felt, about the core issue: the Church, where it comes from, where it is going, its role in the world, etc. Valencia, July 1, 2003

Padre Pica returned to Bolivia in early 2004, and his demons were waiting for him. In his memoirs, he writes that he hopes his sexual orientation and the abuses will end “with some major event (an illness or an accident).” Months later, his hopes would be fulfilled.

“Well, apparently my time has come. The moment has arrived, the disease. I have cancer! In a few days, with the surgery of my prostate, lymph nodes, and seminal vesicles, I will become impotent. […] I know now that either way, I will be impotent (without testicles, there is no metastasis). Cochabamba [Bolivia], April 12, 2004

Pica, however, does not believe that God is speaking to him “in the language of illness,” but instead, prays that his faith will return to him, and that his torments will disappear. In the final years of his life, the priest finally admits to his homosexuality, rejecting it as a “sin” that will condemn him to hell. He insists on the church’s hypocrisy on the subject, and laments how sexual repression has caused him so much harm. “How could the Church allow and encourage that? Jesus would never have treated me like that,” he writes of the institution’s condemnation of homosexuality.

[Photo caption: Jesuit priest Alfonso Pedrajas.]

It is during these years that Pica began a stable relationship with his partner — the man to whom he confessed his past abuses and revealed that he was writing his memoirs. During this time, the priest also returned to the school where the abuse took place, Colegio Juan XXIII in Cochabamba to receive a tribute for his years of teaching. Pica, surrounded by cheers and praise, writes that he felt happy to return. But also uncomfortable: “I was a little fed up with all the speeches, full of praise and affection, but that to me sounded hypocritical or, at least, untrue; because I know perfectly well what the reality was, and I cannot shake from my mind the deep feeling of guilt that overwhelms me.” In his diary, he writes that some events were suspended.

Another meeting/homage that had been planned for La Paz was called off at the last minute. Someone insisted on bringing up the old complaint to Ramón [Alaix, Pica’s provincial superior]. Ramón got scared. He even talked about sending me to Spain. I put the brakes on it as best I could, and so far, he hasn’t mentioned anything about what he had promised to do: to talk to the concerned person again and ask for him for forgiveness. El Paso [Bolivia], February 3, 2008

To dispel the rumors, Pica sent a letter to school alumni explaining that he was the one who had canceled the tribute, because he had cancer and every Wednesday received chemotherapy. “I recognize the bad things that have been done, for which I ask your forgiveness,” he wrote. Months later, however, Pica agreed to let a group of juanchos organize a birthday party for him.

[Photo caption: Pica at a party celebrating his last birthday before his death.]

The life of Alfonso Pedrajas, of Padre Pica, was fading away. He stopped writing in his diary on October 11, 2008. A year later, he would die in a hospital bed. His diary is the memoir of a pedophile. It is also proof of how the Church tolerated these crimes within its walls, and worked to systematically cover them up. Pica himself acknowledged as much:

“I have told it so many times…”

EPILOGUE

The secret diary

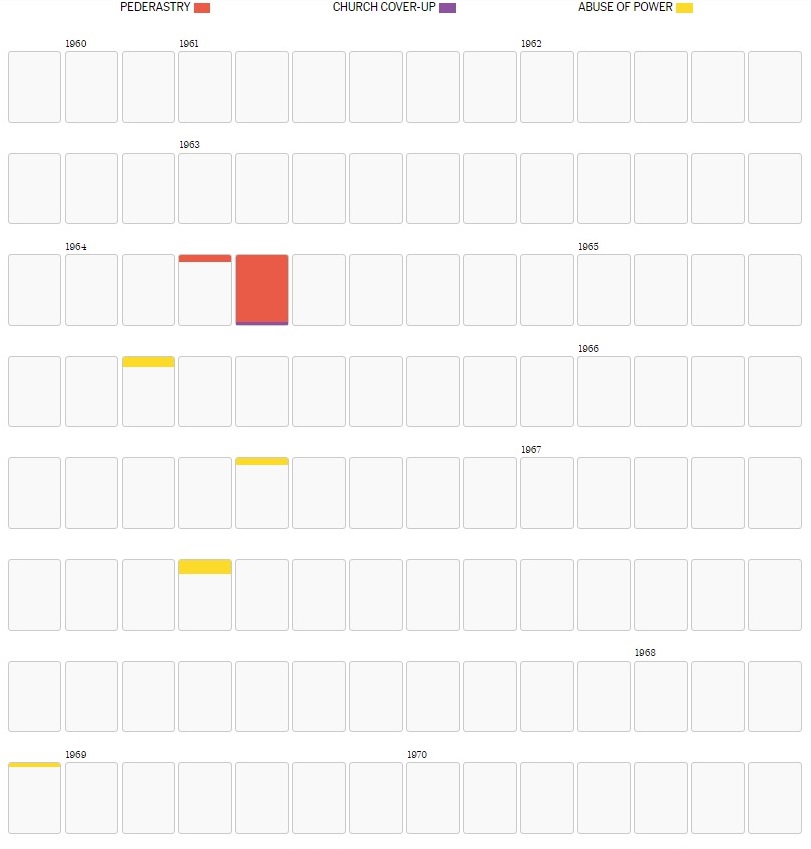

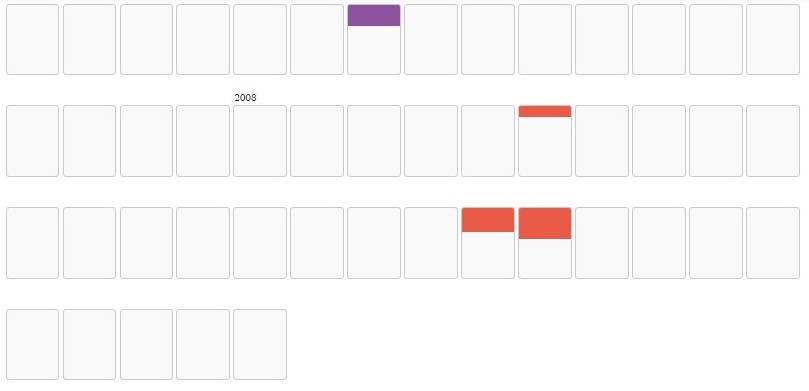

EL PAÍS conducted an in-depth examination of the diary of the Jesuit priest Alfonso Pedrajas, also known as Padre Pica, to distinguish between personal information without journalistic relevance and passages referring to child sexual abuse. The text consists of 383 A4-size pages.

Below is an infographic depicting the results of that analysis

CREDITS

Coordination and layout:Brenda Valverde Rubio and Guiomar del SerArt and design:Fernando HernándezProduction:Carlos MuñozAudio editing: Nicolás TsabertidisEnglish translation:Max Granger

EL PAÍS launched an investigation into pedophilia in the Spanish Church in 2018 and has an updated database with all known cases. If you know of a case that has not seen the light of day, you can write to: abusos@elpais.es. If it is a case in Latin America, the address is: abusosamerica@elpais.es.

THE STORY’S REPERCUSSIONS

FERNANDO MOLINA/JULIO NÚÑEZ

The Bolivian Episcopal Conference (CEB), a body of Roman Catholic bishops, on Wednesday asked for forgiveness over the abuses committed by Alfonso Pedrajas, after the story came out in Spanish on Sunday. “We condemn these actions, we feel solidarity with the victims who have suffered acts of sexual abuse, we ask for their forgiveness, and we want to tell them that we share their suffering and disappointment for these serious events that have marked their lives and have been a cause of deep pain,” said a statement.

Meanwhile, the Society of Jesus in Bolivia has filed a police complaint to initiate an investigation into the case. Bernardo Mercado, the provincial [the highest position of the congregation in the country], also announced that the Society of Jesus has sanctioned eight former high-ranking officials of the order accused of covering up Pedrajas’ crimes. The order has not yet released the names of these former high-ranking officials.