(CANADA)

Nunatsiaq News [Iqaluit, Nunavut, Canada]

July 25, 2022

By Randi Beers

As Pope Francis’ visit to Iqaluit looms, accused priest remains sheltered from charge in France

The Catholic Church has promised to help bring one of its priests charged with sexually assaulting Inuit children to justice, but whether that priest ever steps into a courtroom is likely up to him alone.

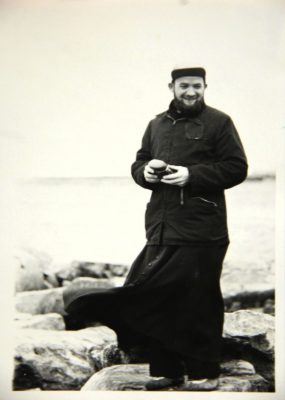

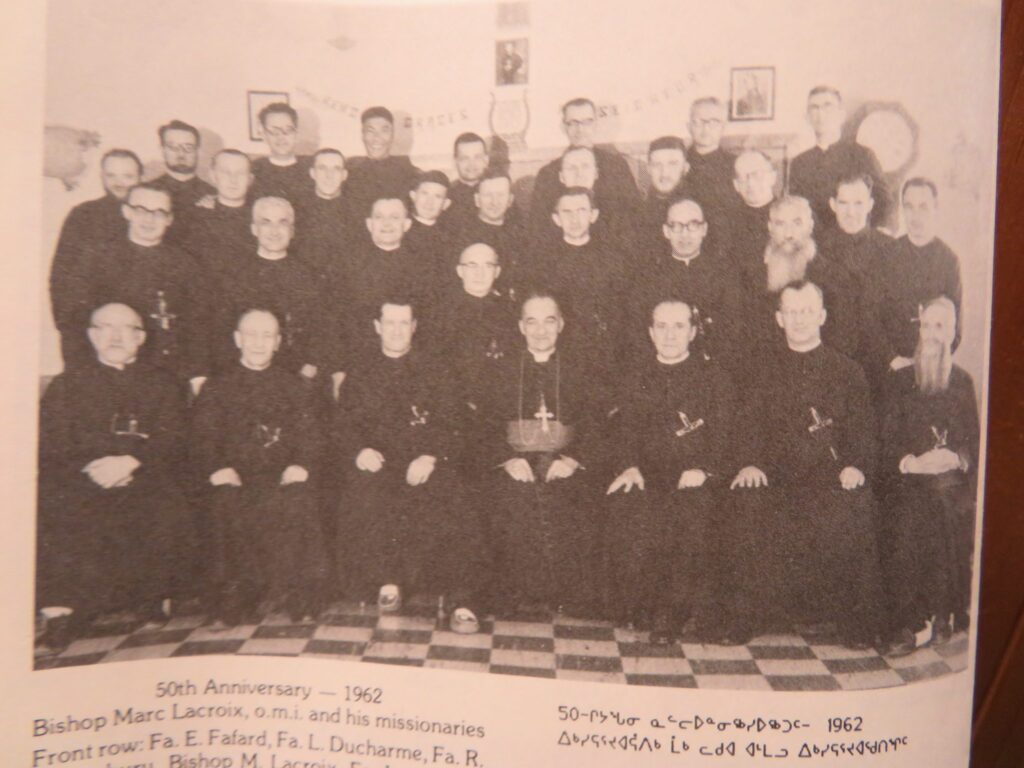

Johannes Rivoire, 91, spent more than 30 years in Nunavut, mostly in Arviat and Naujaat, between 1960 and 1992.

While his name often comes up in the context of residential schools, he never worked within the residential school system.

Rivoire’s responsibilities were those of a parish priest: He performed mass, taught catechism, presided over funerals, officiated weddings. In his free time, he kept a greenhouse, growing lettuce and radishes in soil cultivated from seaweed.

He is also accused of sexually assaulting boys and girls during that time, some as young six years old.

Rivoire left Canada in 1993, saying his father was ill and needed him in France.

Something else happened that year. People started to speak up about things they said Rivoire had done to them.

It would take years for those accusations to result in charges, and many more years for those charges to come to light.

The first three charges were laid in December 1998 — one count of historical indecent assault against three boys in Naujaat, and two counts for sexually assaulting a girl under 14 years of age in the same community.

By the time the world found out about them, it was 2013 and he was nestled in France, out of reach of Canada’s justice system. This is where he remains.

The first set of charges were stayed in 2017, as the Public Prosecution Service of Canada concluded there was no reasonable chance of conviction.

In February of this year, the RCMP laid a fourth charge of indecent assault, involving a young girl in Arviat and Whale Cove from incidents alleged to have occurred between 1974 and 1979.

The Catholic Church agreed to help make sure Rivoire faces this charge, in a commitment made during a visit by a Canadian Indigenous delegation to the Vatican in April to seek an apology for historical abuses.

Three months later, as the Pope’s scheduled July 29 visit to Iqaluit approaches, the Catholic Church has not provided any detail about what that promise entails, and there is little hope among legal experts and victim advocates that it will amount to any meaningful action.

Karen Bergman believes Rivoire’s departure from Canada was triggered by a letter she sent to church leaders in 1992.

Bergman, who was living in Arviat at the time, said she heard the accusations and felt the bishop of the Churchill-Hudson Bay diocese, Rev. Raynauld Rouleau, who is now retired, needed to hear them too.

So she wrote to him.

Bergman said she believes her letter spurred the church to quietly usher Rivoire out of Nunavut.

“I trusted [Rouleau] to do the right thing,” said Bergman.

“My thought was, ‘You guys deal with this,’ and look what happened. They protected him.”

Rouleau has not responded to multiple requests for comment.

Back in France, Rivoire has evaded extradition for decades because, although Canada has an extradition treaty with France, France’s Penal Code protects its citizens from it. Rivoire, being a French national, is protected under this law.

“It’s a very firm principle,” says Robert Currie, a professor at Dalhousie University’s Schulich School of Law.

“It rules out him getting extradited to Canada for sure.”

Rivoire could also hypothetically be charged in France for the crime he’s alleged to have committed in Canada, because Canada’s extradition treaty with France allows France to adopt Canada’s charges, in lieu of extradition.

But France also has a statute of limitations on sexual assault. Once a minor who was sexually assaulted turns 18, that person has 30 years to report the allegation.

It’s unclear whether the statute of limitations has passed in Rivoire’s case, and the Canadian Department of Justice will not confirm or deny whether any discussions have occurred with France regarding the charge against him.

“Both extradition requests and any communications between Canada and an extradition partner are confidential state-to-state communications,” said Ian McLeod, a spokesperson for Justice Canada.

France’s Ministry of Justice has not responded to a request for comment about whether it plans to adopt the charge against Rivoire.

While Currie said there are good reasons for diplomatic discussions around extradition to happen in private, he added the extreme amount of secrecy the federal government operates under in these cases is needless.

“There is a strong case [Rivoire’s victims] were heinously victimized,” he said. “I think Justice Canada could go a lot further in telling the public what’s going on.”

If Justice Canada and France’s Ministry of Justice can’t — or don’t plan to — pursue Rivoire’s assault charge, what power does the Catholic Church have to intervene?

Pope Francis could summon Rivoire to Rome, where the Vatican could try him in its own court, said Currie, but the same hurdle remains: Rivoire has the right to choose whether he wants to heed that summons.

“It would be like if your employer said you have to come to the head office in the U.S.,” Currie said.

“Rivoire has managed to fend off every effort to prosecute him. At his advanced age, I’m speculating [about] him saying, ‘I don’t care.’”

The Vatican has not answered requests to clarify whether Pope Francis himself has reached out to Rivoire, but others within the church have, such as Rev. Ken Thorson, the provincial of the Oblate of Mary Immaculate Lacombe Canada.

“I have urged Father Rivoire to make himself available to the justice system,” Thorson confirmed, apparently, to no avail.

Today, Rivoire sits in a public retirement home called Saint-François d’Assise, in the centre of Lyon, France.

Rivoire has made himself available to French reporters twice in the past year, face to face, to discuss the allegations against him.

Both stories paint a picture of Rivoire’s life today: He rarely leaves his room, except for meals, he has eczema which makes it difficult to move, and he dresses like a relic of the past.

“With pants fitted high on his stomach and his sleeveless hunting vest, you’d think he had come out of a film devoted to postwar agricultural France,” reported Le Monde, in a French-language story, published in March.

As for facing the charge against him:

“Why should I go there?” Rivoire told Le Progrès in a French-language interview published in May.

“If they want to talk to me, they have to come. I’m 92 years old, I have a lot of [health] problems. I haven’t left my room for more than six months except to eat. If anybody wants to see me, like you, let them come see me.”

There is one person out there who thinks visiting Rivoire on his own turf is an interesting idea.

Lieve Halsberghe, a victims advocate based in Belgium, was instrumental in making sure Eric Dejaeger, a defrocked priest convicted of a variety of sex crimes against Inuit during his time in Nunavut in the 1970s and 1980s, faced his charges.

She was also the one to alert the media in 2013 to the charges against Rivoire.

Today, Halsberghe has little faith in the Catholic Church to make good on its commitment on the accused priest.

“If you have to wait for them to fulfill their promises, come back in the year 25,000,” she said. “Their words are not worth anything. They have been promising, evading, lying forever.”

She said it’s time for Rivoire’s alleged victims, and their families, to take matters into their own hands: They could fly to Lyon and tell their stories.

“Talk to the French people about what that man did before he dies,” she urged. “It’s the only way of obtaining any kind of tiny bit of justice.”