ROUND LAKE (NY)

The Daily Gazette [Schenectady NY]

July 30, 2022

By Andrew Waite

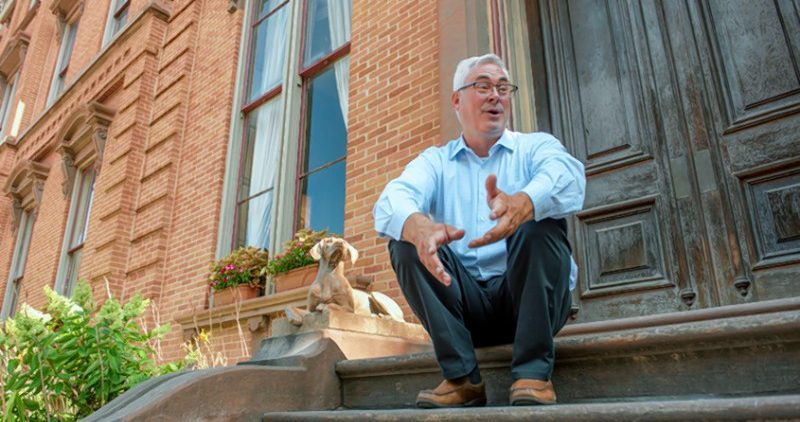

Stephen Mittler first met Mark Haight on the steps of the Corpus Christi Church in August of 1988. Mittler was 12 years old at the time, a typical kid who played outside, rode his bike and, occasionally, had a little too much fun playing with matches.

Church wasn’t especially important to Mittler, but it was a centerpiece of his upbringing. And church mattered to Mittler’s parents. His father, a social worker, was a priest in the 1960s and early ’70s, and every Sunday morning at 10:30 the Mittler family — Stephen, his twin older brothers and his mother — would take their place in the third row at Corpus Christi.

Haight arrived as a fill-in pastor in the summer of 1988. He’d already been transferred out of multiple parishes, but Mittler would only later learn of the priest’s dark history and contend personally with Haight’s brutality. At the time, all Mittler knew was that his father had befriended Haight during his own days in the priesthood and that Haight seemed to take particular interest in Stephen, which felt good.

On that August day in 1988, Haight, now 73 and living in Schenectady, invited Mittler, his father and brother, Jim, to fly on a privately leased Cessna plane. They took off from Schenectady County Airport, flew over Saratoga Race Course and Saratoga Lake, and circled the Mittlers’ house in Ballston Lake, where Mittlers’ mother stepped outside to wave.

Mittler had never before been on a small airplane, so like any 12-year-old might be, he was gleeful the entire ride. What the blond-haired, blue-eyed pre-teen didn’t know then was that the airplane trip was the beginning of Haight’s grooming process.

“That’s the face of a monster,” Mittler said in an interview this week, detailing his story. “He knew he had access to teenage boys, so he struck.”

While Haight denied allegations of abuse or pleaded the fifth during a court deposition last year, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany agreed in June to pay Mittler $750,000 to settle a New York State Child Victims Act lawsuit. As part of the deal, Haight agreed to pay $2,000 to Mittler. The settlement is one of the first major Child Victims Act settlements by the Diocese of Albany. Passed in 2019, the Child Victims Act allows those who are victims of child sexual assault to bring civil lawsuits up until their 55th birthday — as opposed to 23. Mittler is 47.

Mittler’s trial had been scheduled to begin last week. Ahead of the trial, Mittler made the decision to tell his story under his own name, instead of using the pseudonym John Doe. Now that the case is settled, Mittler remains committed to sharing his story.

“What I think it says is that these people should be believed,” Mittler’s attorney, Matthew Kelly, said of the settlement. “The church lied to people, and what it should mean is that the Pope should clean house in the Albany diocese.”

On Sunday, Mittler is scheduled to appear publicly with Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany’s Bishop Edward Scharfenberger at 10:30 a.m., ahead of the 11 a.m. mass on the steps of Corpus Christi Church in Round Lake. The meeting is a result of pressure applied by Mittler after diocese leadership promised to walk with victims of abuse but never initiated action, Mittler said.

Kathy Barrans, a spokeswoman for the diocese, confirmed Scharfenberger will attend the Sunday meeting, but she said the diocese did not want to comment ahead of the event out of respect for Mittler.

“We don’t want to make it about the diocese,” Barrans said.

Shortly after agreeing to a settlement with Mittler, Scharfenberger announced a settlement plan that provides for a court-approved mediation process to resolve more than 400 pending victim/survivor cases against the diocese.

Scharfenberger’s Sunday meeting follows a week in which Pope Francis visited Canada and offered apologies for abuses of Indigenous youths at Catholic-run boarding schools from the 1800s to the 1990s.

Sunday’s meeting will also take place on the very steps where Mittler first met Haight more than three decades ago.

“I want to ask some very direct questions. I don’t know what they are yet, but I want to make sure that other people see they can hold someone accountable without being aggressive,” Mittler said. “I call it a campaign of awareness and a campaign of transparency. There is so much that has happened behind the scenes that the diocese simply doesn’t want to share.”

Grooming and abuse

After the Cessna ride, Haight continued grooming Mittler. Having the trust of Mittler’s parents, Haight regularly invited Mittler to his cabin in Thurman in Warren County.

Together, Mittler and Haight would work on projects. They’d paint a schoolhouse, build a deck or a shed. They’d garden.

Mittler always spent time with Haight alone, and the day trips eventually became overnights.

Within months, the wrestling moves began. Haight would playfully push Mittler and Mittler would push back. That led to full-on wrestling, which led to molestation and rape.

“Those details truly blend together,” Mittler said. “I know the frequency that I was there, but the actual details blend together, almost like one event.”

After the abuse began, Mittler said, he felt helpless.

“I recall not knowing what to do,” Mittler said. “So I never did anything.”

What Mittler did was live with his secret. He recalls returning from abusive episodes at the cabin only to come home and cuddle with his girlfriend, whom he had through most of high school.

The abuse continued throughout Mittler’s time in high school. Even when Haight was sent to treatment at the Servants of the Paraclete facility in New Mexico in 1990, he stayed in touch with Mittler, sending pictures and notes. One mailing, dated April 1990, shows a photo taken inside a Cessna and says, “Steve, you could’ve been in this seat!”

When Haight returned to New York, Mittler went back to the cabin. On the drives up, he said, he’d be looking forward to whatever project was in the works for the trip, despite the inevitability of nighttime abuse.

“Why would I continue to do that? It’s an answer that I can’t give myself,” Mittler said. “It’s hard to reconcile that, but with therapy and treatment I know it’s not my fault. It’s OK to be vulnerable again in life, to be able to have these intimate conversations, so I’m in a really good place.”

Living with a secret

Despite the abuse, Mittler found his way in life.

After high school, he attended SUNY Plattsburgh, where he had the usual keg-party-and-dating college experiences. After graduating, he eventually got married, had two children, pursued a successful career in banking and settled in Saratoga Springs. He also ran unsuccessfully as a Republican for a Saratoga County Board of Supervisors seat in 2019.

For decades, Mittler simply compartmentalized to get by. One illustration of what he was up against? Haight was a guest at Mittler’s wedding in 2000.

“He was still friends with my father,” Mittler said.

Mittler also said, to this day, he thinks of Haight whenever he hears a Cessna.

In 2016, Mittler had a reckoning. He said his life was fraying as his decade-and-a-half-long marriage eroded, the way marriages sometimes do.

Mittler went on a 10-day, nonreligious retreat, thinking he had to work through the grief of losing his family and marriage.

“The entire conversation led to clergy abuse. I wound up being treated more for clergy abuse than I was for the loss of my marriage. It was pretty powerful,” Mittler said.

That realization, along with uncovering photos and other evidence of his experience with Haight, motivated Mittler to consider taking action.

Legal action

Mittler filed his lawsuit under the Child Victims Act in August of 2019. It was among the first lawsuits to be filed under the law.

Ordained in 1976, Haight was moved by the church from job to job and was twice placed in treatment before ultimately being removed from his final position at Glens Falls Hospital in 1997, according to Mittlers’ lawsuit. Haight’s first treatment was at the House of Affirmation in California, prior to meeting Mittler, according to Haight’s Jan. 18, 2021 deposition, which was part of the lawsuit. The deposition also alleges retired Bishop Howard Hubbard, who faces abuse allegations of his own, knew of Haight’s behavior.

In a deposition released earlier this year by a state Supreme Court justice in Albany County, Hubbard stated under oath that he was aware of reported sexual abuse and sent priests who committed abuse to treatment facilities before allowing them to return to churches.

After Haight was terminated from the priesthood in 1997, the Albany diocese paid a $997,500 victim settlement to a man who said Haight abused him as a minor as early as the 1970s, Haight’s deposition shows.

Accused of sexually abusing multiple boys over a period of more than a decade, Haight has never been charged with or convicted of any crimes.

Closure for Mittler

At a settlement conference in June, Mittler revealed that he no longer wanted to use a pseudonym in the case.

“When the court addressed me, I said I no longer want to be referred to as Mr. Doe. I want to be Stephen Mittler.”

All eyes in the courtroom turned to him in that moment, and the feeling of empowerment was incredibly cathartic, he said. So, too, was finally telling his brothers about the abuse this May.

“They were pissed. They were overwhelmingly angry,” Mittler said.

But a quieter, even more personal, moment for Mittler came in March, when he and Haight were in the same courtroom for a summary judgment hearing. At the beginning of the hearing, he and Haight locked eyes.

“He looked back at me for five seconds and then he looked away,” Mittler said. “That was it. I was done with him.”

Andrew Waite can be reached at awaite@dailygazette.net and at 518-417-9338. Follow him on Twitter @UpstateWaite.