DALLAS (TX)

Dallas Morning News [Dallas TX]

March 31, 2022

By Kristen Torralva

[Image above: The Rev. Don Dickerson was allowed to advance within the Society of Jesuits order even as Jesuit leaders knew he had sexually abused boys. Confidential records from the Order’s province in St. Louis are becoming public as a result of a lawsuit brought by nine Dallas-area men.(Tom Fox / Staff Photographer )]

Years before leading Jesuit Prep, the Rev. Phillip Postell participated in a decades-long system of shuffling priests across southern states amid child sex abuse allegations.

In July 1984, the Rev. Edmundo Rodriguez received a familiar phone call about one of his priests. A family in Louisiana reported to their church that the Rev. Don Dickerson had made sexual advances toward their 12-year-old son.

This was the sixth allegation against Dickerson of sexual misconduct with young boys and Shreveport was the third city the Society of Jesuits New Orleans province had moved him to because of allegations.

Rodriguez typed a letter to Philip Postell, a director for the province who oversaw schools, and suggested three options: Allow Dickerson to stay in Shreveport on the condition he undergo counseling, relocate him to another city, or put him on a leave of absence from the church.

Postell wrote back that he was not surprised about the accusation against Dickerson, but he stressed that Rodriguez must evaluate the veracity of the allegation. If it were true, Dickerson undoubtedly needed to be removed from Shreveport, Postell said.

“No matter what, Dickerson has to know that this is the last straw — one more report and he would be dismissed,” Postell wrote.

Confidential records held in St. Louis, the province headquarters, are now being released as a result of a lawsuit brought by nine men in the Dallas area. The lawsuit, alleging abuse in the late 1970s and early 1980s, was filed in 2019 against the Catholic religious order, Jesuit College Preparatory School Dallas and the Catholic Diocese of Dallas. Lawyers for the parties agreed Wednesday to a settlement that calls for reforms in how the school, the Diocese and the religious order handle abuse reports. Details about the financial compensation for victims remain undisclosed.

The Jesuits Society, a Catholic religious order with clergy all over the world, assigns its priests to schools and churches located in areas they serve. The USA Central and Southern Province oversees Dallas’ Jesuit College Preparatory school for boys.

The Dallas Morning News read hundreds of pages of documents, many of them kept secret for more than 50 years, and transcripts of depositions lawyers took with some of the priests, including the Rev. Postell, who was the president of Jesuit College Preparatory School Dallas from 1992 to 2011 and remains a prominent figure in the local Catholic community. The school’s athletic stadium was named for him in 2013 and as recently as January he officiated a wedding in Dallas.

The religious order’s handling of Dickerson, revealed in these files, is one example of how Jesuit leaders, including Postell, knew about priests accused of sexually molesting boys and moved them around for decades, keeping the allegations quiet and allowing the priests to reoffend.

This practice has been exposed in hundreds of similar cases around the country, and many Catholic churches and religious orders have responded by publishing names of credibly accused priests in an effort to restore public trust.

Before Postell became president of Jesuit College Preparatory School in Dallas in 1992, he oversaw all priests in the region’s schools and knew about their movements.

Until recently, Postell, 83, lived in Dallas and served as a chaplain to students and alumni. Some of the alumni in the newly settled lawsuit have made allegations about priests Postell directly oversaw.

One of the men suing, former Dallas TV reporter and anchor Brendan Higgins, recently read Postell’s deposition and felt the priest’s attitude was indifferent, as if he were talking about something as casual as a football game.

“This was him committing, in my mind, crimes,” Higgins said. “It was shocking.”

Through his legal team, Postell declined to comment for this article. In January, leaders of the order moved Postell from Dallas to a Jesuit retirement community in St. Louis. Dickerson died in 2018.

The Jesuits USA Central and Southern Province, which includes Dallas, declined interview requests. The Rev. Thomas Greene, leader of the regional order, issued a statement in response to our questions.

“I sincerely apologize to any person who has been impacted by abuse relating to any of our members or former members. Abuse of a minor under any circumstance is a crime and a sin for which perpetrators need to be held accountable,” Greene said. “We have recently resolved several lawsuits because it is our hope to try to bring healing to persons who report they have suffered. We pray for all persons involved.”

The lawsuit names five Jesuit priests accused of molesting boys at Jesuit College Preparatory School in Dallas. At least three of the priests were accused of sexual misconduct before their assignments to Dallas, lawyer Charla Aldous said.

In his deposition with lawyers last year, Postell said he was not aware of many of the allegations of sexual abuse by the five priests while he was the director of secondary schools and oversaw Jesuit College Prep.

“I was aware of almost nothing,” Postell said.

But attorney Brent Walker showed Postell documents he personally wrote that showed Postell was, in fact, aware of multiple allegations against Dickerson. Walker suggested Postell knew about other priests who had been accused more than once. The newly revealed records show Postell was also involved in discussions about several other priests accused of sexual misconduct over the span of his long career.

“I regret it, I’m embarrassed, I am ashamed, I apologize for the harm that it has done,” Postell said toward the end of his deposition.

The Rev. Ronald Mercier, who oversaw the province that includes Dallas from 2014 until Greene took over in 2020, said in a deposition last year that the practice of relocating accused priests was immoral.

“Certainly that would violate everything we stand for today,” Mercier said.

Though the order says it has halted the practice of transferring accused priests, the local victims and their lawyers question whether the province now is committed to transparency.

Seven strikes

The Jesuit Society started giving Dickerson breaks before he was ordained, records show.

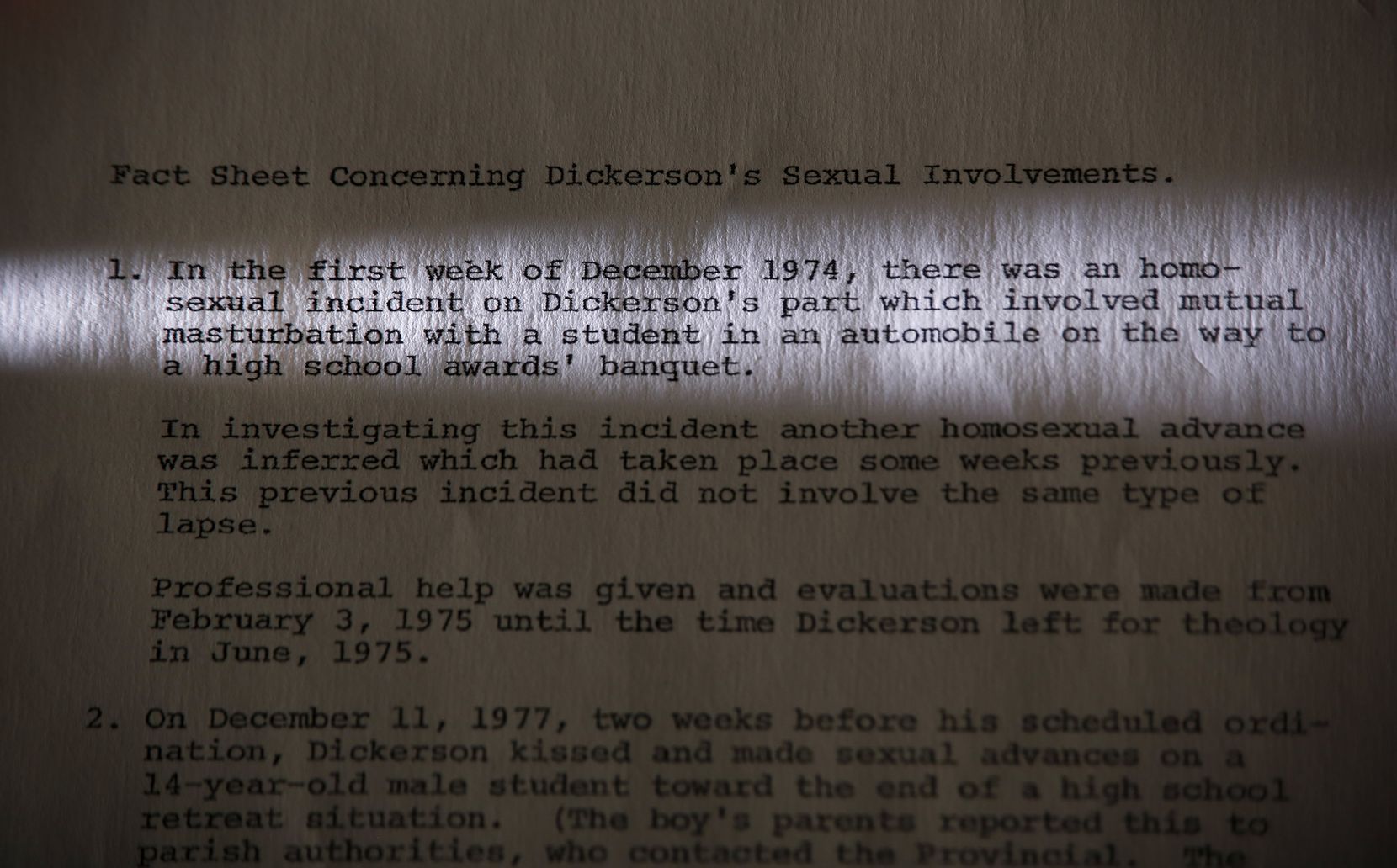

In 1974, while Dickerson was studying to become a priest, he masturbated two high school boys, according to letters between Jesuit leaders that were uncovered in the lawsuit. A group of priests noted the incidents in a March 1975 meeting, but unanimously voted to advance Dickerson to the next level of his training, records from the meeting show. He was ordered to undergo weekly psychological sessions and special examinations for pedophilia.

Dickerson was scheduled to be ordained in December 1977. But seven days before the event, the southern region’s leader, Thomas Stahel, wrote a letter to the head of the Jesuits saying Dickerson had kissed a 14-year-old boy and made sexual advances toward him. The boy, a student at Brebeuf Jesuit Preparatory School in Indianapolis, told his parents, who reported it to Stahel. Dickerson admitted to making sexual advances on the boy during a high school retreat, according to Stahel’s letter.

Dickerson’s ordination was delayed. Records show a psychiatrist treated Dickerson for an undisclosed amount of time before deeming him to no longer be a risk to children.

Dickerson was fully ordained in 1980 in Alabama.

Dickerson’s next assignment was Jesuit College Prep in Dallas. The Jesuit order did not tell campus leaders about earlier accusations against him, Postell said in his deposition last year.

Not even a year later, in July 1981, a letter from Postell to Stahel and Rodriguez said they removed Dickerson. Letters showed that a child’s parents had come forward to the school with an accusation against Dickerson.

The principal of Jesuit College Prep at the time, Brian Zinnamon, discovered the earlier accusations against Dickerson and was angry the Jesuits Society had not warned him, Postell said.

In response to a lawyer’s questions, Postell conceded that he should have reported Dickerson to law enforcement. Rodriguez, who died in 2017, does not appear anywhere in the lawsuit to have answered for his role in moving Dickerson.

Instead, Jesuit leaders relocated Dickerson to St. John’s Parish in Shreveport. But before he left Dallas, he was allowed to stay for a school retreat he wanted to attend. He also was offered a “leisurely vacation” before reporting to his next assignment, letters show.

That following spring, Dickerson coordinated the parish’s first Youth Day at St. John Berchmans School with nearly 300 students from area churches, a church newsletter shows. A smiling Dickerson was photographed at the event. Dickerson’s new assignment didn’t keep him away from young boys.

In May 1982, the Dallas high school principal wrote to Stahel. A second boy in Dallas had come forward to report Dickerson. Zinnamon urged the Society to dismiss Dickerson if another incident occurred, according to his letter.

The records show no evidence that Dickerson faced any consequences related to the accusation.

In April 1984, Postell wrote a letter to Dickerson recommending he advance to taking his final vows to become a full-fledged Jesuit priest. In his deposition, Postell called his recommendation a “tremendous oversight.”

Three months later, Rodriguez received a sixth complaint against Dickerson, records show.

Rodriguez told Postell he saw three options: Allow Dickerson to stay in Shreveport on the condition he undergo counseling, relocate Dickerson to another city or place him on a leave of absence from the church, according to Rodriguez’s letter.

“Why on earth did you not just say, we need to get rid of this guy?” Walker, the lawyer, asked Postell during his deposition last year.

“I’m sure that must have occurred to us,” Postell answered. “I don’t know why we didn’t act more decisively.”

Dickerson got another fresh start. The Jesuits moved him to Austin, where he continued to advance toward taking his final vows.

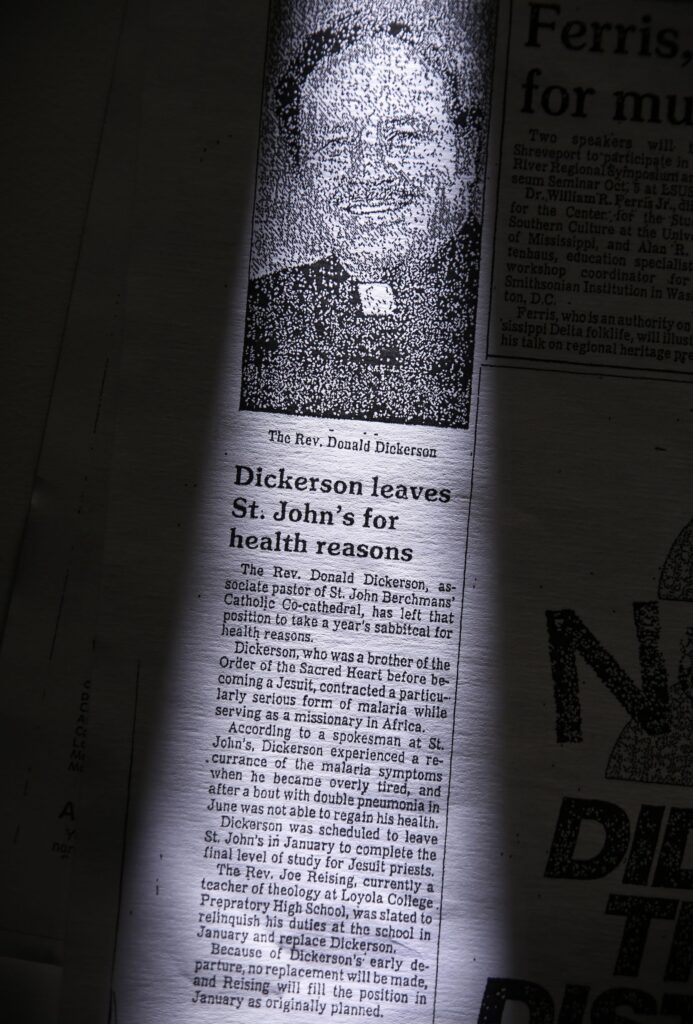

The local newspaper, the Shreveport Journal, reported that he was taking a yearlong sabbatical after contracting malaria on a missionary trip to Africa.

In his deposition last year, Postell conceded that explanation was not true.

In February 1986, the church received a letter from a family reporting that their son said Dickerson was “feeling and touching on him in ways he shouldn’t have been.”

Rodriguez wrote a confidential memo about what was now the seventh documented accusation against Dickerson. He must be afforded the benefit of the doubt and the accusation should not be publicly discussed, Rodriguez wrote.

“After all, we are dealing with a man’s reputation and future apostolic availability,” Rodriguez wrote.

A few days later, Dickerson wrote a letter to Rodriguez requesting to be dismissed from the order. He thanked the priests for providing counseling over the years and for reassigning him to a position that was “designed to keep me from harm’s way.”

“It is clear to me now that these measures have not been enough to prevent my falling again into problems which become public and have the potential of harming the Society of Jesus and the Church seriously,” Dickerson said.

Nowhere in the letter does Dickerson express condolences to his victims or characterize his actions as sexual abuse. In a March 1986 letter, Rodriguez told the Society of Jesus in Rome that Dickerson had chosen to leave the church due to “homosexual incidents.” He did not specify that Dickerson had been accused of sexually abusing children.

“It is with regret that I must ask you to dismiss Father Dickerson from the Society of Jesus because he is a good man and a zealous apostle,” Rodriguez wrote.

Rodriguez added that the Society intended to continue providing resources to Dickerson, including a car and psychiatric treatment. Dickerson was removed from the Society in 1986, 12 years after the first child reported Dickerson’s abuse to the Jesuits.

‘Very bad public relations’

By the time Postell and Rodriguez had to respond to the accusations against Dickerson, the practice of relocating priests amid abuse allegations had already become customary within the order.

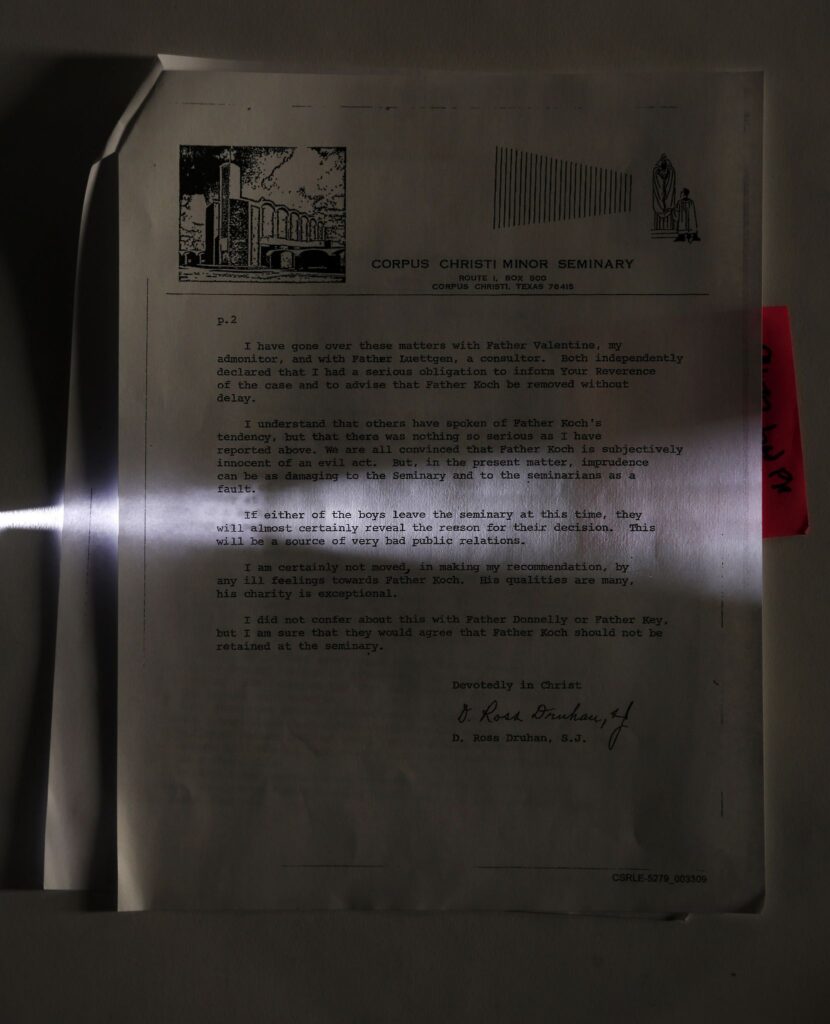

In 1965, the Rev. Ross Druhan feared the Jesuit school in Corpus Christi was on the verge of being exposed.

He had been silent about a longstanding problem with the Rev. Patrick Koch on what Druhan characterized as his “demonstrations of affection” with boys at the school.

In a letter Druhan wrote to Jesuit leaders in New Orleans, he said he had to speak with Koch every year about similar reports.

Druhan had kept those complaints quiet. But now, two more students had complained that Koch kissed and touched them and they were threatening to leave the school if Koch was not removed.

“If either of the boys leave the seminary at this time, they will almost certainly reveal the reason for their decision,” Druhan wrote. “This will be a source of very bad public relations.”

The boys provided more details to another priest, who also wrote an undated letter. The boys said Koch opened their shirts to rub their stomachs and kissed them. One of the boys said Koch gave him alcohol until he was drunk, then removed his clothes and got into bed with him.

A year later, in January 1966, Koch was reassigned to a Jesuit high school in New Orleans.

In a letter to the Bishop of the Diocese of Corpus Christi, Druhan said staffing in New Orleans was the reason Koch was being moved.

In 1971, Koch was transferred to Jesuit College Prep in Dallas, where he rose up the ranks, serving as principal for seven years and president for one.

He was reassigned in 1994 to Sacred Heart Church in Tampa, Fla., where he remained until his return to Dallas in August 1997. In a letter that June from the Jesuit head, James Bradley, to the Dallas Diocese, Bradley wrote, “I am unaware of anything in his background which would render him unsuitable to work with minor children.”

In Dallas, Koch wore many hats, according to a 2006 article in The News about his death. He taught in the classroom, served as director at Montserrat Retreat House at Lake Dallas, worked as director of priestly formation at Holy Trinity Seminary in Irving and was an associate pastor in St. Rita Parish.

In December, the Central and Southern Province of the Jesuit order added Koch, who died in 2006, to its list of credibly accused priests after two of the Dallas plaintiffs, Higgins and Mike Pedevilla, filed the lawsuit and shared their stories of abuse with The News.

Higgins gave credit to Greene, the new head of the regional province. Before Greene entered the Jesuit Society, he was a lawyer and prosecutor. Higgins and his lawyers said they felt a shift in the way the order has treated them since Greene took over in 2020.

“There’s been a big change in leadership on the Southern Province that has come with a new level of respect, cooperation and empathy for the victims,” Higgins said.

But more work still needs to be done, Pedevilla said.

‘Transparency

In an effort to reckon with past abuse, the regional order that includes Dallas released its first list of credibly accused priests in December 2018. The list now includes 14 priests who were stationed at Jesuit College Prep in Dallas at some point in their careers. Mercier, who was head of the region at the time, wrote that the decision to publish the list was for the victims, foremost, and for the church’s congregants.

“One consistent theme has emerged, the need for transparency through publishing this list of Jesuits with credible accusations of abuse of a minor, painful as it may be,” Mercier wrote.

As a result of a national abuse scandal, many Catholic churches and religious orders created review boards to investigate accusations against priests. The Jesuit order that includes Dallas followed suit in 2002 and created a regional board. The group, made up of professionals who have worked in law, medicine and psychology, investigates allegations against priests and makes recommendations on those cases to the head of the region.

But ultimately the decision to place a priest on the list of those who are credibly accused is left to the sole discretion of the regional leader. Documents related to the investigations remain confidential, except for any information released through lawsuits.

Lawyers Walker and Aldous, who represent Pedevilla, Higgins and others who said they were molested by priests in Dallas, question whether the process is transparent enough. They worry that other allegations could remain secret if the decision to name priests rests with one man.

Mercier said in a deposition last year that the review board holds the order accountable. But he opposes the suggestion to reveal the board’s deliberations or the investigative files.

But as a result of the settlement this week, the school and the religious order pledge to also promptly notify law enforcement when they receive accusations.

Until late last year, Koch, who was named by the Dallas and Corpus Christi dioceses in 2019, had not been added to the list. Three of the Dallas men bringing the lawsuit allege Koch molested them and they were offended that the Jesuits left him out.

Nowadays, priests get one strike and they’re out, Mercier said.

“If there is any credible allegation of abuse … one case is sufficient to mean that that person is barred from active ministry from that point on,” Mercier said.

For the Dallas men suing, that change came too late.