MONTCLAIR (NJ)

NorthJersey.com [Woodland Park NJ]

March 9, 2022

By Mike Kelly

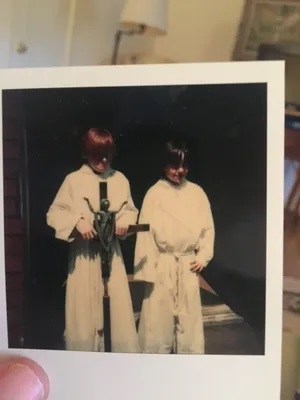

[Photo above: David Ohlmuller, right, with his older brother, Brad, as an alter boy at St. Cassian Roman Catholic Church in Montclair, New Jersey. David was abused as a boy by a Catholic priest. He recently rode his bicycle from Chicago to New Jersey to draw attention to the Catholic sex abuse crisis. The journey was chronicled in the documentary film, Peloton of One.]

A lone cyclist pedals along a rolling road as cars pass.

This is David Ohlmuller.

He is 52 now, divorced, the father of a college-bound son, a hall of fame champion paddle tennis player and a long-distance cyclist. He was also abused by a Catholic priest when he was an altar boy in Montclair, New Jersey.

He rides his bicycle to exorcise that memory.

This is a long ride that has been depicted in a new, award-winning documentary film, “A Peloton of One,” which chronicles Ohlmuller’s bicycle trek from Chicago to New Jersey to draw attention to clergy sexual abuse. The film, which has already won the JP Morgan Chase Audience Award at the Greenwich International Film Festival and was featured by the Los Angeles-based Laemmle Virtual Cinema, is being released this month to a variety of video-on-demand platforms.

Victims of sexual abuse often tell us their emotional wounds never really heal. Yes, they might win a lucrative cash settlement — as Ohlmuller did from the Catholic Church after hiring Boston attorney Michael Garabedian, whose groundbreaking efforts to expose sex abuse in the church were depicted in the 2015 Oscar-winning film “Spotlight.” And yes, they may have achieved all sorts of success, in business, in sports and in their adult lives.

But the lingering childhood pain and shame never disappear, especially if the abuser is a religious figure.

Psychologists say any form of sex abuse of a child is bad enough. But when the molester is a church official — a representative of God — some experts describe the abuse as the equivalent of “soul murder.”

‘We want to know what we can do to help others understand’

Dave Ohlmuller knows that feeling all too well.

In 1982, he was lured into a confessional, he says, at St. Cassian’s Catholic Church and abused by the Rev. Michael “Mitch” Walters, who has since been removed from active ministry and has reportedly been allowed to live in a priest’s retirement home in Rutherford. Ohlmuller was only 12 at the time.

For the next year, he says, Walters regularly abused him, stopping only when Ohlmuller quit his job as an altar boy.

Ohlmuller did not know it at the time, but Walters allegedly was abusing at least four other children, including a 14-year-old girl. The victims discovered one another only after they filed lawsuits decades later against the Newark Archdiocese.

For years, Ohlmuller tried to bury the memory of what happened. He became a top-flight tennis player for St. Peter’s Prep in Jersey City and then at Loyola University in Baltimore. After college, amid jobs on Wall Street and with a sports marketing firm, he won eight national championships in platform tennis and was elected to the sport’s hall of fame.

Meanwhile, Ohlmuller battled alcoholism and drug abuse, not knowing that both were linked to his own abuse as a child.

When his now-18-year-old son turned 11, the memories of his abuse flooded back. In his own son, Ohlmuller saw himself. He vowed to protect his son from the pain he suffered.

So he went public with his secret of what happened in that confessional at St. Cassian’s Church in Montclair.

But merely telling his own abuse story — and winning a $200,000 settlement from the church — was not enough, Ohlmuller felt. He felt he needed to find a way to focus attention on the issue and rewrite New Jersey’s statute of limitation laws to allow adults who were abused decades earlier as small children to file criminal complaints and lawsuits against their molesters.

Hence, the documentary film.

“As survivors we immediately think what can we do,” said Joe Capozzi, who said he was abused as boy by the Rev. Peter Cheplic, a priest assigned to St. Matthew’s Catholic Church in Ridgefield. Cheplic, also removed from active ministry, reportedly lives at the same priest retirement home as the priest who allegedly abused Ohlmuller.

Capozzi went on to write a play, “For Pete’s Sake,” which has been performed off-Broadway in Manhattan.

“For me, I wrote about my experiences,” said Capozzi, who signed on as a producer of the documentary film featuring Ohlmuller. “As victims, we want to know what we can do to help others understand what we went through.”

For several weeks during fall 2018, Ohlmuller rode a Trek Domane road bike nearly 800 miles between his apartment in Lake Forest, Illinois, and the Hudson River waterfront in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Ohlmuller’s bike, which cost nearly $3,000, was donated by a friend who was inspired by his courage to come forward about his abuse. A camera crew, financed with more than $150,000 in other donations and directed by Ohlmuller’s St. Peter’s Prep classmate and documentary filmmaker John Bernardo, followed every pedal push.

The goal, said Bernardo, was to use the narrative of a cycling trip as a springboard to examine the internal journey by Ohlmuller — and other victims — to face what happened to them years before and find a way to move on.

“We’ve all heard stories about sexual abuse,” Bernardo said. “But the scale of it really affected me. It’s not just the Catholic Church. It’s sports institutions and the Boy Scouts. The breadth of this problem and the cover-up was incredible.”

An explosion of allegations and lawsuits

Investigators are still trying to determine the extent of sex abuse by Catholic priests across the nation.

More than 5,000 American priests have been formally linked to abuse cases since the 1950s — “credibly accused” is how the church formally describes them. But experts say the real number may exceed 10,000.

That amounts to less than 5 percent of Catholic priests — a figure that church officials say corresponds to roughly the same rate of abuse by non-clergy adults. But such explanations by the church hardly mitigate the pain for victims and the efforts to hold the church accountable. So far, the American Catholic Church has paid nearly $4 billion in settlements to victims, with eight dioceses declaring bankruptcy.

New Jersey has been especially hard hit. None of the state’s four dioceses and one archdiocese have filed for bankruptcy. But when the state suspended the statute of limitations for civil sex abuse complaints for two years, beginning on Dec. 1, 2019, state courts were flooded with lawsuits.

By the time the filing deadline arrived last November, more than 820 lawsuits, alleging sex abuse by priests, teachers, brothers and nuns, had been filed against the Catholic groups in New Jersey.

Other Northeastern states, such as New York, Pennsylvania, Connecticut and Massachusetts, with high numbers of Catholic schools and parishes also report increases in lawsuits.

The most notorious case involves former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, who led the Newark Archdiocese and the Metuchen diocese for nearly two decades. McCarrick is linked to several cases in New Jersey and New York in which he reportedly abused children.

He also allegedly ordered young men studying for the priesthood at the Newark Archdiocesan seminary on the campus of at Seton Hall University in South Orange to sleep in his bed at a church-owned house in the Jersey Shore town of Sea Girt. Yet another lawsuit claims McCarrick was involved in a child sex ring with several New Jersey priests, including Walters.

Walters, 67, whose last known address was the St. John Vianney retirement home for priests in Rutherford, could not be reached for comment.

The Newark Archdiocese declined to respond to several requests for comment about Walters’ whereabouts and why he listed his address as a retirement home sponsored by the church. In a separate statement, the archdiocese said it was “not familiar” with the documentary film “or its content” featuring Ohlmuller.

But, through its spokeswoman, Maria Margiotta, the archdiocese released a statement saying that it “takes all allegations of abuse seriously, and remains fully committed to its comprehensive programs and protocols to protect the faithful and to working with survivors of abuse, their legal representatives, and law enforcement authorities in an ongoing effort to resolve allegations of past abuse.”

‘This really challenged my faith’

Ohlmuller said he distrusts such promises from church officials.

“I haven’t been to church in decades,” he said. “I absolutely believe in God. I pray every day. But this really challenged my faith like no other.”

Such sentiments, say experts, are common among those abused by clergy.

Robert Hoatson, a Catholic priest who served in Bergen County but was dismissed from the priesthood by the Newark archdiocese after he disclosed that he had been abused and devoted himself to helping abuse victims such as Ohlmuller, said Catholicism is “too corrupt” to reform itself.

“The whole sandbox has to be emptied,” said Hoatson, who appears in the documentary film and runs the Road to Recovery program for abuse victims.

Danielle Polemeni, now 52 and living in Columbus, Ohio, said she was abused by Walters when she was 13 and the first female altar server at St. Cassian’s in Montclair.

She thought she was alone, however. She had no idea that Ohlmuller allegedly had been abused by the same priest and that others were also victims.

Like Ohlmuller, Polemeni suffered in silence for years, coming forward only after other victims spoke out.

“For a long time, I thought what happened to me was normal and this is what happened to girls,” she said in an interview. “For a long time, I thought it was my fault. But you’re not alone and it’s not your fault.”

Reaching that conclusion was not easy, Polemeni said.

“That child that felt shame and that child that felt silence is always living inside of you,” she said.

Unlike Ohlmuller, Polemeni still attends Catholic Mass. She also teaches English at St. Francis de Sales Catholic high school in Columbus.

“My faith is very deep,” said Polemeni, who appears in the documentary. “This sex abuse crisis is not going to change if I stay home. I love my Catholic parish. I love the school where I teach. I don’t want to give the abusers the power if I stay away.”

That’s not the case with Ohlmuller’s parents, who now live in Spring Lake, New Jersey.

His mother, Ginna, and his father, Raymond, were raised Catholic and attended Catholic schools and colleges. Neither attends church now.

Raymond, now 82 and a retired vice president for Becton Dickenson and Company, grew up in Teaneck and won a scholarship to the prestigious Regis High School in Manhattan, where he played basketball on the same team with Dr. Anthony Fauci, the longtime head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and now the chief medical adviser to President Joe Biden.

Raymond went on to play basketball for Georgetown University and received his law degree from Fordham University. After retiring from Becton Dickinson, he attended Mass at his parish in Montclair every morning.

Now, because of his son’s abuse at the hands of a priest and what he felt was the church’s lack of accountability, Raymond no longer sets foot in church.

“We don’t go anywhere near a Catholic church unless we drive past it,” Raymond said.

His wife, Ginna, 78 and the former executive director of the American Platform Tennis Association, now describes the Catholic Church as “practically a criminal organization” for its cover-up of the abuse scandal.

“The cardinals knew the abuse was taking place. The bishops knew it. They knew it way back,” Ginna said. “They just did the same thing. They just sent these priests to other parishes and wiped their hands of it. It gets me absolutely horribly sad. It gets me enraged. It’s been a horrible, horrible thing.”

David Ohlmuller knows firsthand the horrors of sex abuse. But he counts his blessings, he says, by just taking one day at a time.

“I’m just glad that I’m here alive,” he said.

Mike Kelly is an award-winning columnist for NorthJersey.com. To get unlimited access to his insightful thoughts on how we live life in New Jersey, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: kellym@northjersey.com

Twitter: @mikekellycolumn