BOSTON (MA)

Boston Globe

December 1, 2021

By Kevin Cullen

Phil Saviano always downplayed his courage in refusing to abide by the Catholic Church’s demand for confidentiality, insisting he only did so because he thought he was going to die soon. But his unflinching bravery gave hope and inspiration to survivors of sexual abuse everywhere.

In 1964, Phil Saviano was 11 years old when the pastor of St. Denis Church in Douglas, a predator with a Roman collar named David Holley, cornered him in a hallway near the sacristy.

As Holley sexually abused him, Saviano could hear muffled voices in the church, praying.

The abuse continued for a year, moving to the church basement, where Saviano could hear the groundskeeper cutting the grass outside.

Confused, afraid, andfeeling he couldn’t tell anyone because they’d never believe him, that he’d be punished for accusing a priest of the unspeakable, he did what every good little Catholic boy did: he went to confession.

He knelt in the confessional booth, in the muffled darkness, and the priest slid back the cover to the small window, spilling a warm glow and a shock: Father Holley, the priest who had abused him, was sitting there waiting to hear his confession.

For a boy that age, in that place, at that time, it was soul-crushing.

When he gave that account of his ordeal, in interviews and speeches, including in 2002, it was revelatory — not just for the extent of the horrific crimes covered up by an institution and its leaders who were more concerned about saving face than saving souls, but for the bravery Saviano showed in telling, in the most intimate and humiliating detail, what was done to him.

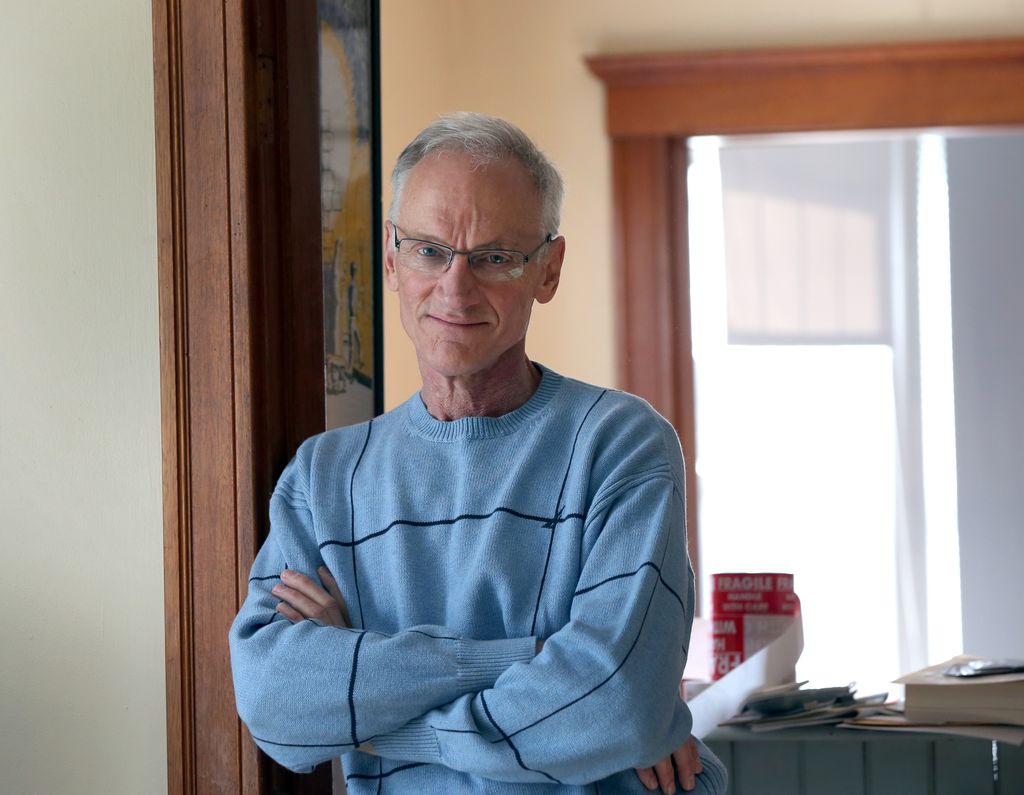

Saviano, who died Sunday at the age of 69, will always be remembered and admired for saying no, for spurning the type of confidentiality agreements that Catholic leaders had used for so long to cover up the sexual abuse of minors —trading a little cash for a signature and silence. He empowered and became the local face of a survivors network that did so much to tear down the curtain that hid generations of abuse. He helped launch this newspaper’s Pulitzer Prize-winning coverage of the scandal, and was portrayed as a groundbreaking whistle-blower in an Oscar-winning film about it.

But one of the most striking things about Saviano was how humble and unassuming he was. He always downplayed his refusalto abide by the Catholic Church’s demand for confidentiality.

“If I had not been dying of AIDS, I would not have had the courage to come forward,” he told The Boston Globe in 2009.

But it always struck me that, facing his own mortality, it would have been easier for him to just take the money and keep quiet.

When Saviano told the Diocese of Worcester where to stick its confidentiality agreement, it was the mid-1990s. Back then, those abused by priests did not break their silence, enter the public square and find a large, empathetic, supportive community waiting to believe and comfort them.

Why, given how little time he thought he had left, submit himself to the questions and judgment and attacks on his character that were sure to follow?

Given what the Catholic Church preaches about the selflessness of Jesus Christ, it was supremely ironic that, like Christ but unlike somechurch leaders who claim to follow his way, Saviano thought of others more than himself. He lost his faith in organized religion but, as someone who suffered at the hands of those who grotesquely style themselves moral vanguards, gained a deep, abiding belief in the dignity of survivors, andgave voiceto so many others who would not or could not speak out.

He was, after all, a professional communicator. More importantly, he was a thoroughly decent human being.

His mother’s people hailed from the former Czechoslovakia and during visits to Prague, Saviano became aware and an admirer of Jan Hus, a Catholic priest who dared to call out the corruption of his own leaders. For his trouble, Hus was burned at the stake in 1415, becoming a symbol of principled defiance.

There is a statue of Hus in Prague, and on that statue are the words which translate to “Truth Prevails.”

It could be Saviano’s epitaph.

Kevin Cullen is a Globe columnist. He can be reached at kevin.cullen@globe.com.