BUFFALO (NY)

Buffalo News [Buffalo NY]

November 15, 2021

By Jay Tokasz

At age 87, Monsignor Ronald P. Sciera might not have much time left to clear his name of the child sexual abuse allegation lodged against him in an August lawsuit.

But the priest of 60 years said his reputation is not his main concern.

“I have to answer to God,” he said. “I have a hope that justice will be served, and the truth will come to light.”

An unnamed plaintiff alleges Sciera molested him nearly five decades ago at St. Aloysius Gonzaga parish in Cheektowaga.

Sciera denies sexually abusing anyone. He says the claim is false, and he has no idea who brought it.

If the lawsuit were to proceed in State Supreme Court, the plaintiff would have to explain in detail what Sciera allegedly did. Sciera would get the chance to respond. Ultimately, if the case went far enough, a jury would decide who was telling the truth.

But the case is unlikely to go to trial because the Buffalo Diocese is in federal bankruptcy court proceedings, which supersede the state court lawsuits and shield the diocese and its 160 parishes from having to defend against them.

Michael Taheri, Sciera’s attorney, said the diocese’s bankruptcy filing is a miscarriage of justice both for childhood molestation victims and for clergy who have been accused of abuse.

“Certainly, there are clergy that abused children and certainly there may be situations where there are false allegations,” said Taheri. “But here I think certain accusers understand that by making an accusation they aren’t ever going to go to a trial in these cases. They aren’t going to ever have to confront Father Ron or any priest.”

The lawsuit accusing Sciera of abuse was filed Aug. 12, two days before the closing of a two-year Child Victims Act “window” that allowed sex abuse cases outside the normal statute of limitations to proceed. While several Buffalo Diocese priests are facing more than a dozen abuse allegations, in Sciera’s case there is a single accusation. The plaintiff, AB 729 DOE, is identified only as a current resident of New York State who attended St. Aloysius Church as a child.

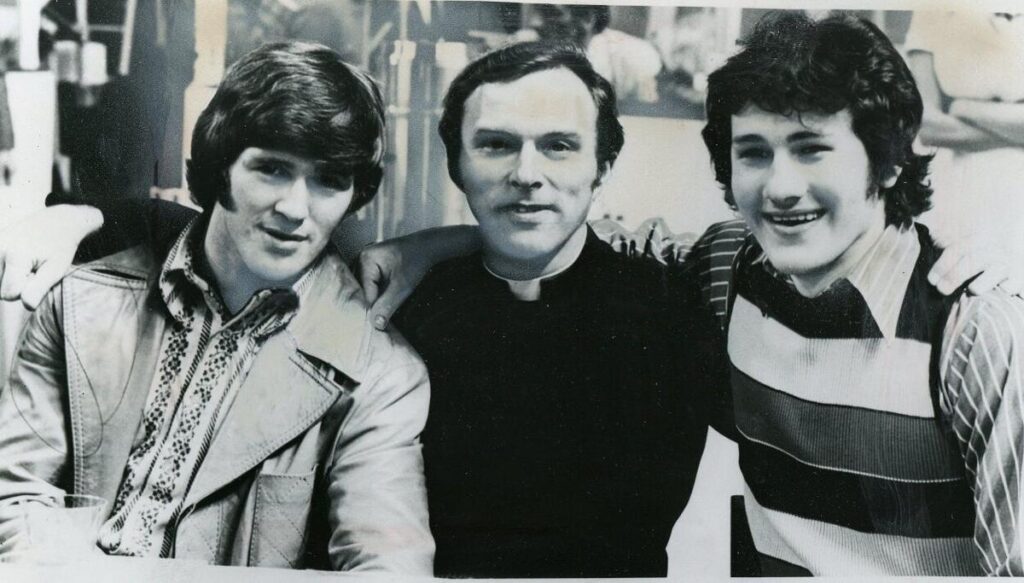

He alleges Sciera molested him in 1972, when he was 13. With 2,000 families, St. Aloysius was one of the largest parishes in the diocese at the time. Sciera was an assistant pastor, along with two other priests, according to the diocese’s 1972 directory. The pastor was Auxiliary Bishop Pius A. Benincasa.

There are no other details about the abuse in the lawsuit, which was filed by attorneys Jeffrey R. Anderson and Steve Boyd.

Boyd said his client did not want to be interviewed for this story. He also said the matter will be resolved in federal bankruptcy court or State Supreme Court.

“We have every confidence in our client and in the process and we look forward to letting the legal matter proceed,” said Boyd, who declined to comment further.

In an October ruling, Chief Judge Carl L. Bucki of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court Western District of New York allowed Child Victims Act lawsuits in state courts against individual priests to move ahead, while extending until next August a stay that prohibits any movement on lawsuits against the diocese and other Catholic entities, including parishes and school.

Most of the more than 750 Child Victims Act lawsuits in Western New York courts involving Catholic entities name as defendants the diocese, parishes, and schools – and not individual priests, many of whom are deceased. In lawsuits where the accused priests are alive, including the case involving Sciera, some plaintiffs’ lawyers chose not to name them as defendants.

Taheri said not naming Sciera as a defendant allows the unnamed plaintiff to pursue a piece of a monetary settlement in bankruptcy court, without having to prove Sciera abused him and without giving the priest an opportunity to answer the allegations.

“It’s one claim, pretty thin. There’s no forensic evidence. The plaintiff has the obligation to prove this occurred,” said Taheri. “Why didn’t they sue Father Ron? He never gets to come to court and testify. That’s pretty unfair. And yet the plaintiff can collect money.”

After learning of the abuse allegation, Bishop Michael W. Fisher suspended Sciera from performing any public ministry as a priest – a restriction that Taheri is attempting to have reversed due to a lack of evidence.

Diocese spokesman Greg Tucker said diocese officials were aware of a single allegation against Sciera, who remains on administrative leave pending an investigation.

“Our legal counsel has been attempting to gain the cooperation of the claimant and has thus far been unsuccessful,” said Tucker.

After becoming aware of an abuse allegation, the diocese in recent years typically has hired an investigator to examine the claims, interview potential witnesses and deliver an opinion to a review board, which then makes a recommendation as to whether an accused priest should be returned to ministry due to lack of evidence or placed on permanent leave.

The diocese cleared a few priests after an investigator determined through complainant interviews that the accusations were not credible or could not be substantiated. That has prompted some lawyers and accusers to refuse the investigator’s interview, saying they don’t trust the diocese’s process and would rather leave the cases in the hands of the civil court system. Lawyers are often reluctant to have their clients interviewed about their claims during litigation anyway. The diocese has cleared other priests after complainants refused to be interviewed.

Taheri has appealed Sciera’s case to Rome, asking Pope Francis to reinstate the priest. Taheri sent along the results of a polygraph test by a certified polygraphist in Florida who asked Sciera if he ever sexually assaulted or molested any minor child while working as a priest in Buffalo.

Taheri also sent 75 letters from Sciera’s friends, fellow priests and others attesting to his character. Some of the letters were from people who took trips with Sciera when they were children and said that he never acted inappropriately with them.

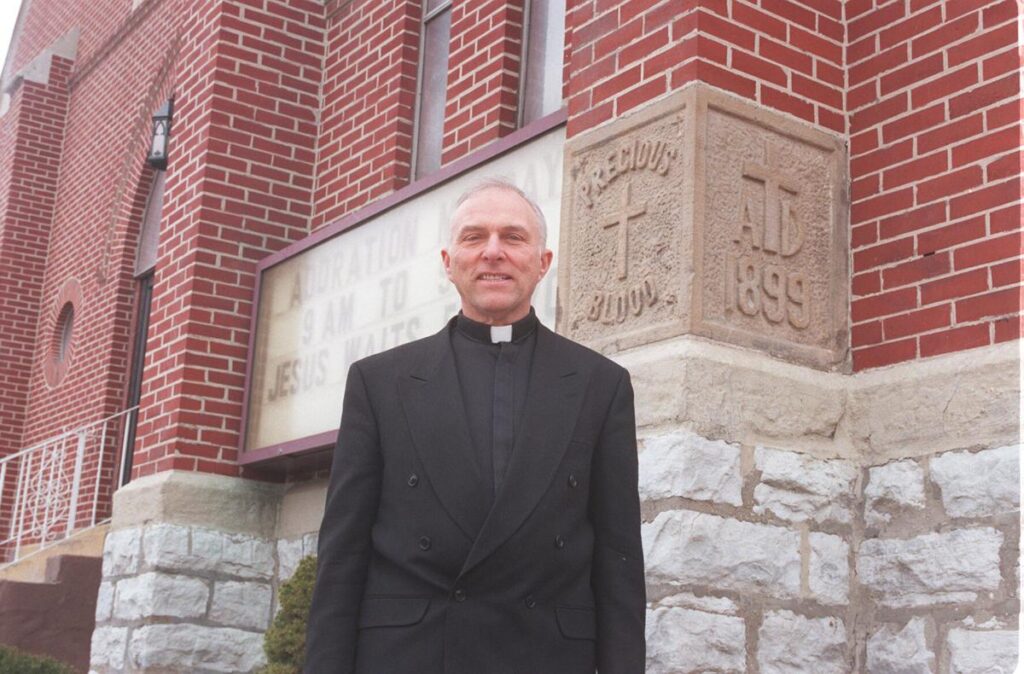

Sciera spent much of his later priesthood as pastor of Precious Blood, a small parish on Buffalo’s East Side that was closed in 2007. As a younger priest, Sciera was known for hobnobbing with the French Connection line and other NHL hockey players as the unofficial chaplain to the Buffalo Sabres. He also maintained a friendship with Pope John Paul II, who appointed Sciera to the board of the John Paul II Foundation in 1996, a post that brought the priest regularly to Rome for foundation meetings.

Sciera said he doesn’t get around that much anymore. He’s been retired for years and lives with a family in Florida.

As part of the restrictions on him, he can no longer hear confessions, which is what he misses most, he said.

But Sciera views his current situation in spiritual terms, describing it as a “gift from God” that has allowed him to identify with the suffering of others and unite it to the sufferings of Jesus Christ.

“I pray every day for my accuser and for his lawyer. I pray that I will meet them in heaven someday,” he said.