CHICAGO (IL)

Anchorage Daily News [Anchorage AK]

November 13, 2021

By Nancy Lord

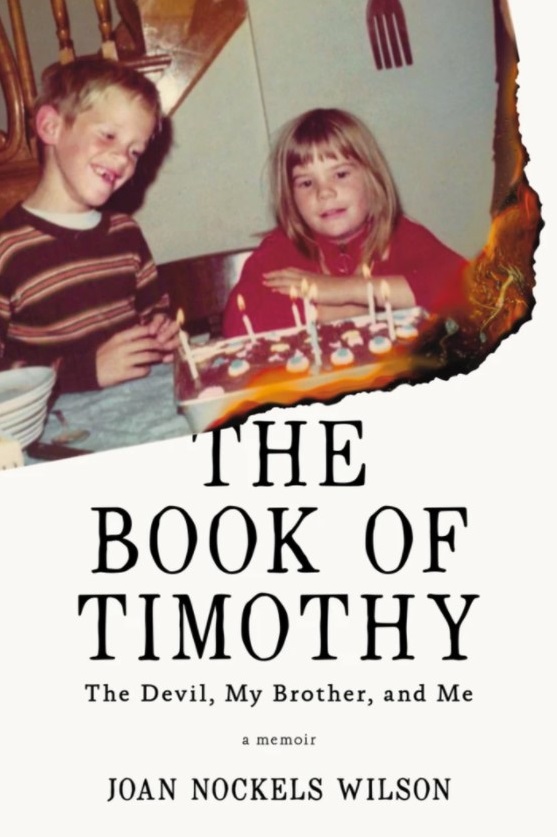

The Book of Timothy: The Devil, My Brother, and Me

By Joan Nockels Wilson. Boreal Books/Red Hen Press, 2021. 320 pages. $18.95.

Sexual abuse of children by clergy is once more in the news. Last month, a new report estimated that some 330,000 French children were abused by Catholic clergy and other authority church figures dating back to 1950. This first accounting by France of a global scandal found that at least 3,000 French priests abused children and that that abuse was covered up in a “systematic manner.” Once again, we are all reminded of the extent of abuse and, once again, the church apologizes.

“The Book of Timothy” opens with a 2002 phone call from the author’s brother in Chicago, where the two had grown up, to Wilson in Anchorage. The story of clergy abuse in Boston had just hit the news, and Tim was upset. He told his sister, “It happened to me.” Thus begins the decade-long fight by Wilson to seek justice for her brother and other boys who’d been abused in Chicago by a priest she names as Father John Baptist Ormechea. The story culminates in a visit to Rome to confront the priest, who had eventually been transferred to the Vatican both to protect him and children he might continue to abuse.

The author, an Anchorage resident trained as a prosecutor, takes her research, analytical and legal skills as well as her “big sister” protectiveness to the entire endeavor. She is unrelenting in her quests for understanding and vengeance and in her documentation of what she discovers. A Catholic from birth, raised in a church-going family and parochial schools, she explains church doctrines, the pull of faith and her own wavering beliefs. The book’s title, we learn, refers to not just the story of her brother but to two epistles in the New Testament attributed to Apostle Paul and consisting of counsel to his younger colleague. Brother Timothy was named for the man venerated as an apostle, saint and martyr. In odd coincidences, the Biblical version, a somewhat obscure text, repeatedly shows up in Wilson’s life, as in the hands of a man she meets on a plane.

The author’s Chicago family was working-class — her father and other family members worked primarily as firefighters — and included six girls and one boy. Priests to them were representatives of God and were never to be doubted. Ormechea visited the family often, staying for meals and “counseling” young Tim in his bedroom, behind a closed door. Wilson, a year older than her brother, was uncomfortable with the closed door, but the family never questioned the “counseling.” It may be hard, today, to understand the lack of questioning, but such was the trust placed in the Church and the innocence of the time. When Tim was 16 and tried to tell his father what had been happening, his father rebuked him. Later, the Illinois statute of limitations for criminal arrest passed.

There were other boys, also victims of Ormechea. Wilson mentions seven she knew of, including her brother, but uses pseudonyms to protect the privacy of the others. It would be hard to definitively tie behaviors in later life to priest abuse, but the now-men, as she describes them, had troubled adult lives involving substance abuse, pornography and relationship difficulties; one apparently killed himself.

In any case, this is not a book about victims and the harm done to them. It is principally about the author’s own 10-year search for understanding and some form of justice. Readers will come away with greater understandings of the role of faith in individual life, the way entire families are affected by trust betrayals, the traumatic effects of reopening life events that some would prefer to forget, human weakness not just in abusers but in those who fail to report known abuse, and the psychology of abusers — the narcissism that prevents empathy for others and the practice of “grooming” victims and their families.

Considerable drama surrounds Wilson’s weeklong trip to Rome in 2012, and it’s best if readers follow that part of the story themselves. No one wants to be told how a mystery novel ends, and the situation is similar with this real-life story. A leavening of the suspense will be found in long passages describing the author’s time in Rome, where she responds positively to the iconic buildings and statuary, and where she confronts her own spiritual and possibly forgiving self.

“The Book of Timothy” is weighty in multiple ways. The story — not recommended for bedtime reading — is disturbing as well as tremendously important. It’s also a thick volume that digresses into multiple memories of the author, family and community history, and the joys of parenthood. It does all tie together, but the segmented structure, which jumps around in time and place, can make for a confused following of the chronology.

In the end, this is a book about love and family devotion. Like her family of firefighters, Wilson responded to the emergency call. “Run always towards the flames and then, of course, always return home.”