COLUMBUS (OH)

Columbus Dispatch [Columbus OH]

September 8, 2021

By Danae King

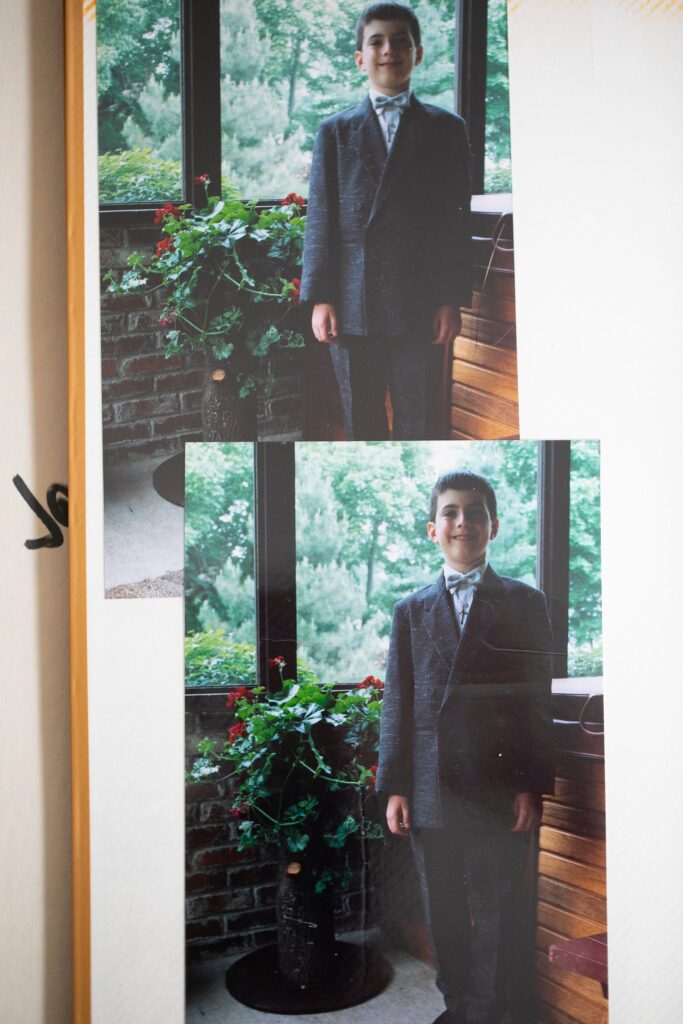

Chris Graham shares his story of being sexually abused by a Catholic priest when he was 14, and how the memories of it have impacted his life.

[Photo above: Chris Graham cries as his mother, Lynne, reads an essay that he wrote about his faith while in college. Graham was emotional because he didn’t remember his 1997 rape by the Rev. Raymond Lavelle at the time he wrote it. -Courtney Hergesheimer/Columbus Dispatch]

The metal clink of a belt being unbuckled.

The room coming in and out of focus.

The pressure with which the older man pinned him to the floor.

These are a few of the memories that come back to Chris Graham in snapshots from years ago, when he was raped by a Catholic priest at St. Joan of Arc Catholic Church in Powell.

He was 14 years old.

Graham was a dedicated altar server at the time who looked up to priests at the parish so much that he considered becoming one.

Today, the 39-year-old podcaster and business coach from Westerville is working through flashbacks and post-traumatic stress disorder brought on by the childhood trauma he blocked out for more than two decades.

Psychotherapy, which he began last year and is ongoing, helped him remember the March 1997 rape at the hands of the late Rev. Raymond Lavelle, a priest named in 2019 by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Columbus as being credibly accused of sexually abusing multiple minors. Lavelle died in late 2015.

Graham reported what happened to the Delaware County Sheriff’s Office and the Diocese of Columbus earlier this year. Both entities declared the allegation to be credible.

But that alone didn’t fix anything.

“Those wounds were so deep … I was broken,” Graham said. “Trauma echoes throughout your life until you begin to heal.”

‘Reform in the church’

Graham is one of more than 100,000 people who have been abused during childhood by Catholic priests in the past 70 years, an issue Pope Francis has acknowledged as “psychological murder.”

Asked by The Dispatch for comment for this story, the diocese sent written statements but declined requests for interviews with Columbus Bishop Robert Brennan and other officials and said it doesn’t comment on specific cases.

“Our victim assistance program offers assistance to all victims who come forward, in an attempt to provide healing and assure that no one affected by sexual abuse suffers in silence and isolation,” says the statement provided by the diocese.

When Graham reported his abuse to the diocese in February, he said officials told him his was thefourth credible accusation against Lavelle.The diocese said it got the first allegation against Lavelle in 2013, with a police report noting that the alleged abuse happened in the early 1970s at St. Agnes Church on the Hilltop.

After a 2018 Pennsylvania grand jury report revealed that more than 1,000 victims of alleged sexual abuse by more than 300 priests over 70 years, dioceses across the country began releasing names of priests “credibly accused” of sexually abusing a minor. The Diocese of Columbus released its list of 34 priests in March 2019 and has since added names as allegations have been brought forward, making the total now 52.

Still, Graham believes that Columbus hasn’t reckoned with a past in which abusive priests were common. There were three assigned at St. Joan of Arc between 1990 and 2000, all of whom Graham interacted with.

Today, the flashbacks and nightmares that have chased Graham for most of his life are mostly gone, but he remains haunted by the injustice of the abuse he suffered and what he feels is a lack of oversight into priest sexual abuse in the Catholic church.

“We’ve seen scandals take down the most powerful people in the world, and the Catholic church is not beyond the reach of that,” Graham said. “I don’t want that to happen, I want to see reform in the church.”

‘The next thing I knew it was over’

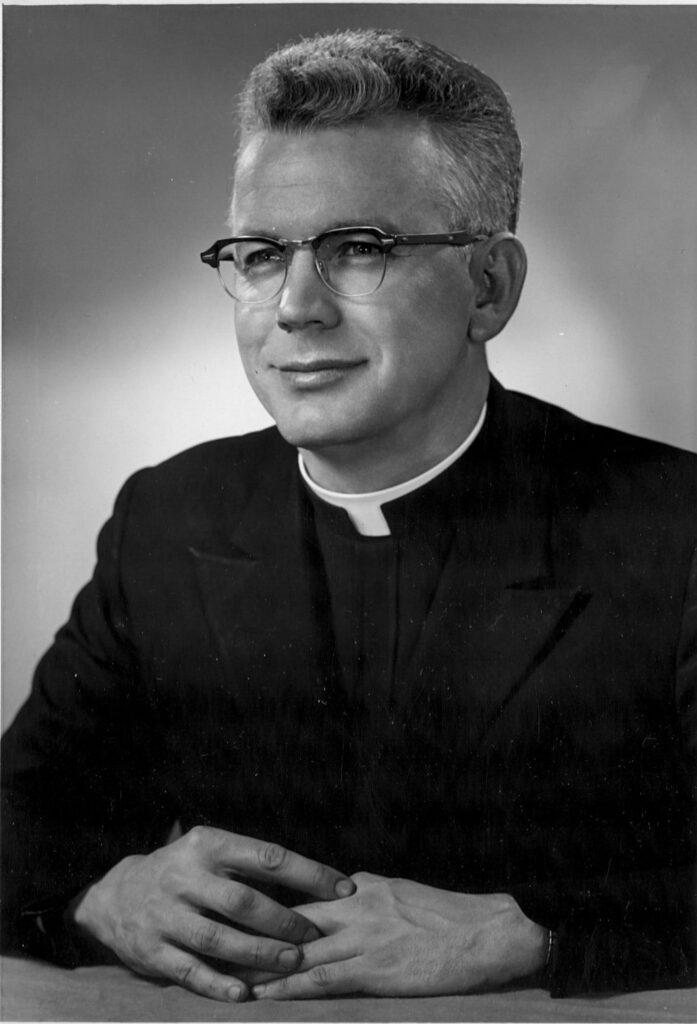

Lavelle, a friendly-looking, stocky, older man with white hair and glasses, was 66 when the abuse occurred.

He was a beloved priest who had had more than a dozen assignments locally before arriving at the church shortly before Graham was abused, just a few years before he retired after 43 years as a priest in 2000.

His arrival at St. Joan of Arc — a large stone building on a generous plot of land that straddles the Franklin-Delaware county line — was much anticipated, Graham and his mother remember.

Lynne, Graham’s mother, remembers the priest as her favorite, as he counseled her through her 1996 divorce with Graham’s father and in dealing with Graham’s continuous disruptive teenage behavior.

Graham remembers looking up to the older man, thinking he was the most “likable” adult he’d ever met.

“I got the sense that he wanted more for me, that he wanted to see me elevated and achieve my potential,” Graham said.

“When someone’s recruiting you, it feels good that you’re special, that you’re different, that you’re more. And what 14-year-old kid whose parents just got divorced didn’t want that?” Graham said. “I think Lavelle saw that desire, and he twisted it and used it to his advantage.”

[Photo: St. Joan of Arc Catholic Church in Powell, where Chris Graham remembers being raped by a priest in 1997. – COURTNEY HERGESHEIMER/COLUMBUS DISPATCH]

On the day of the rape, Lavelle told Graham to drink leftover sacramental wine during Mass. Graham noticed the priest had poured much more than was needed for the assembled parishioners, but he did as he was told, happily. He felt like the instruction from Lavelle was an honor since priests usually drank the leftover holy wine.

When the service ended, he followed Lavelle into the sacristy, a changing room for priests.The other priests and altar servers left, leaving the two of them alone as Graham waited for his mom to come later for choir practice.

“I had had a lot of wine,” Graham said. “I’m feeling kind of weird, like I don’t know how to describe it, just like the dynamic of the room seemed to shift really quickly.”

A few minutes later, the priest stormed out. Then, “he flew back into the room with a big grin on his face, and next thing I knew it was over,” Graham said of the rape.

Graham can remember Lavelle unbuckling his belt, then grabbing him and turning him around. Lavelle partially undressed the teen and then pushed him slowly down to the floor of the room, raping him before standing back up and asking if Graham would like to do the same to him.

The boy declined.

‘There’s no escape’

Although he hasn’t been back since he was a teen, Graham can still picture the church where the rape happened and how he felt afterward.

The maroon-cushioned oak chair where he sat — frozen — once it was over.

How he silently coached himself to get up and run from the room.

The imposing stone walls and wooden beams of the church’s social hall as he fled.

A hulking figure at his back, grabbing for him as he made a narrow escape.

While Graham had flashbacks of being chased for more than 24 years, it took him that long to remember why he was running and who was chasing him.

“There’s no escape,” Graham said.

Graham has come to remember through weekly Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) psychotherapy sessions.

EMDR is a therapy method used to help people recover from trauma and PTSD. Therapists lead clients through the therapy by having them focus on a negative event and doing eye movements to guide the person to notice their feelings, according to the EMDR International Association.

It can be helpful for people with PTSD, as memory loss often accompanies trauma, according to a 2012 Columbia University study, and others. Marci Hamilton, founder and CEO of CHILD USA, a Philadelphia-based think tank tracking state efforts on child abuse, said the memory loss shows in victims of child sexual abuse.

The average age at which victims of child sexual abuse come forward is 52, Hamilton said.

Zach Hiner, executive director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP), said that memory loss and later reporting of abuse is consistent with his experience, as people who seek help from the network are generally older.

“It’s common for traumatic issues to be buried,” he said.

‘The sensory details’

The scraps of memory all fit together now for Graham, who remembers finally gathering the courage — as Lavelle calmly replaced his own clothing — to flee into the social hall.

When Lavelle followed, Graham turned and screamed, “‘What you did was wrong!'”

Then, something extraordinary happened.

Graham remembers the door to the church’s education wing opening and a woman walking through. Not only did her appearance give him a chance to run, but it offered him a witness to Lavelle’s assault.

EMDR helped Graham recall some details about the woman, if not her name. And, when Delaware County Sheriff’s Detective Rashad Pitts tracked her down earlier this year, she confirmed Graham’s story,

She “indicated she recalled a young teen poorly dressed running out of the changing room … appearing to be ‘terrified,’” Pitts wrote in his report, in which her identity was redacted.

She “’remembers (Lavelle) grabbing the kid and ordering him back into the office/changing room.’”

Having a witness to events surrounding a sexual assault, as Graham did, is rare with a late disclosure, Pitts said.

In an interview with The Dispatch, Pitts said Graham was emotional when he recounted the story of his abuse to the detective on Feb. 2. One of the reasons Pitts said he believed Graham’s story is because of the sensory details, such as the click of Lavelle’s belt buckle.

“That stuck out to me,” he said. “(I thought) ‘OK, this is real.'”

‘The memory doesn’t come back, but the feelings do’

Graham was always running.

In his flashbacks, the father of three is running; he and his family were always being chased by a group of people, sinister but unidentifiable.

“The memory doesn’t come back, but the feelings do,” Graham said. “The sense of being chased and there being no escape.”

His PTSD manifested in night terrors, flashbacks while he was awake and a fear of betrayal that Graham said deeply impacted his relationships.

“You’re conscious, you’re hypervigilant,” he said. “Feeling like the boogeyman is coming around the corner.”

This fear created arguments between Graham and his wife; his anger and frustration that she didn’t see the same danger led to him verbally abusing her, he said.

He’s in the process of a divorce now — she declined to comment — and left the home he shared with his family in March 2020 after what he described as a particularly bad flashback, a resulting seizure, and frequent arguments.

It was the beginning of a downward spiral.

In spring 2020, Graham said he was hospitalized because his symptoms were so bad that his family didn’t know what else to do for him. The hospitalization led to him getting counseling and finding EMDR, and he was diagnosed with PTSD in May 2020.

Healing

COURTNEY HERGESHEIMER/COLUMBUS DISPATCH

On a quiet June evening, Graham lay on his yoga mat — flat on his back, hands resting on his chest, eyes closed.

He breathed deeply in and out as Liz Baldridge, the instructor for that night’s class at The Yoga and Fitness Factory in Westerville, led Graham and 17 others through yin yoga.

[Photo: Yoga has taught Chris Graham to connect with his body, whereas before, he would often feel as if he was experiencing things from outside his own body.COURTNEY HERGESHEIMER/COLUMBUS DISPATCH]

Attending at least one yoga class a week — preferably with Baldridge, who has advanced teacher training in trauma-sensitive yoga — is one way Graham has been focusing more on taking care of himself.

Yoga taught Graham to connect with his body, whereas before, he often would feel as if he was experiencing things from outside his own body.

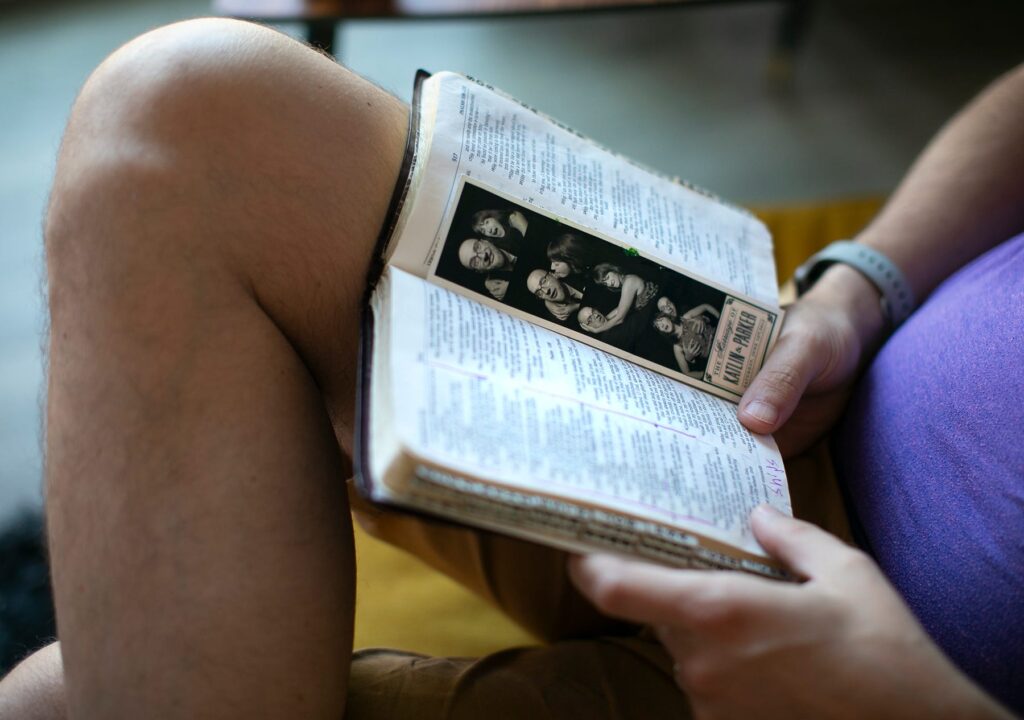

He’s also found healing in a place a victim of priest sexual abuse might not expect: church.

On Sundays, as the lights go down at LIFE Vineyard Church on the Near East Side, the atmosphere feels more like a concert than a church service. Graham absorbs the music, eyes closed and a hand raised as he worships Jesus with others.

Some Sundays, Graham is a member of the worship team, up near the pastor, as he was as an altar boy years ago. A guitar hangs from his neck, a smile on his face.

It has taken him months since his memories began to resurface to be brave enough to get involved in church again.

“Being in a community and being around other people and learning to trust other people is really, really hard for me because there’s a piece of me that screams, ‘Here we go again’ if there’s any sense of duplicity,” he said.

[Photo: Chris Graham plays guitar in LIFE Vineyard Church’s band on the Near East Side, where he has become involved in church again. – COURTNEY HERGESHEIMER/COLUMBUS DISPATCH]

Still, he said, “I just knew … I have to face this,” Graham said.

It helps that he’s found a religious community with a female pastor, not an old, white-haired man.

Melanie Forsythe, lead pastor, grew close to Graham after he reached out in 2020 as he began to struggle. She saw him begin to be honest about his mistakes, stop blaming others and attend services, even though she could see that it was hard for him.

“He had hit rock bottom, and he didn’t know which way was up,” Forsythe said.

Graham said he was never afraid of church, even when he brashly declared himself to be an atheist days after the rape.

“I was afraid of betrayal, and church was the context where betrayal was most likely for me,” Graham said.

He left the Catholic church and religion completely at the time, only coming back to God a few years later through a Young Life camp where authority figures weren’t as threatening and the environment felt vastly different.

Still, Graham said most of his relationship with God takes place outside of church, when he’s alone. Each morning, he takes some time with Jesus and meditates.

“I get freedom. I get healing. I feel safe. I love other people more,” Graham said.

Finding purpose

On a recent day, Graham got to his Westerville office and found an envelope from the Columbus diocese waiting for him.

He held the envelope in his hands for a while before opening it,

He knew what was inside — a long-awaited check, reimbursement for some of the costs of his therapy, promised months ago by the diocese and finally delivered.

“It’s so weird to look at this and see something physical that’s like, ‘Yeah, sorry,'” Graham said.

[Photo: Chris Graham chats with friends after a yoga class. Graham says yoga has helped him deal with the trauma he suffered by being raped in 1997. – COURTNEY HERGESHEIMER/COLUMBUS DISPATCH]

As the months pass since Graham came forward with his story of abuse, he’s pondered how he wants to deal with what happened to him and how God might be able to use him.

“I do feel called by God to help other victims, absolutely I do,” he said.

Graham believes he remembers his rape because he’s equipped to help others and inspire change.

He says reform needs to happen within the Catholic church and in society, and, as he enters this next chapter of his life, he plans to do something about that goal.

Graham has been telling his story to lawmakers in hopes of Ohio laws changing and making it easier for victims to come forward with their abuse when they’re ready, not because laws say when they can.

He also hopes to work with the Catholic church at some point and is encouraged about the potential for change due to Pope Francis’ attitude about abuse and the fact that former defrocked Cardinal Theodore McCarrick is being criminally charged in Massachusetts for sexually assaulting a teen.

[Photo: Chris Graham plays with his new kitten, NASA, after an EMDR therapy session. – COURTNEY HERGESHEIMER/COLUMBUS DISPATCH]

“It seems like the bell has rung, and we’re off to the races,” Graham said. “I think things are going to be moving quickly after this just because it’s so empowering. It’s given me a lot of peace to know, phew, this isn’t that radical coming forward with this.”

As Graham begins work on a new podcast about mental health, trauma and creative people — which will include his story of priest sexual abuse — he says he ultimately hopes his story will help other victims come forward, too.

“I hope light shines in dark places.”

More information

SNAP (Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests) is available to talk to victims confidentially. The group can be reached via SNAPNetwork.org, by calling 614-653-1502 locally or by emailing SNAPCentralOhio@gmail.com.

Anyone who might have experienced sexual abuse by those associated with the Catholic church is encouraged by the Diocese of Columbus to contact law enforcement and the diocesan Victims’ Assistance Coordinator at 614-241-2568, or email helpisavailable@columbuscatholic.org.

Find more coverage of clergy sex abuse in Columbus here and at Dispatch.com.

dking@dispatch.com