(AUSTRALIA)

Australian Broadcasting Corporation - ABC [Sydney, Australia]

September 4, 2021

By Rebecca Turner

[Photo above: Survivor Jarrod Luscombe.]

A Christian Brother left a trail of broken boys behind him. Jarrod Luscombe was one of them, but now he’s helping pick up the pieces and seek justice.

For a long time, Jarrod Luscombe thought he was the only one.

The only one sexually abused as a teenager by the Christian Brother he was once proud to consider his mentor, Brother Daniel Virgil McMahon.

For years he repressed the memory but when it came back, his life as a happily married father-of-two imploded.

“The effects were brutal. Post traumatic stress disorder, severe depression, exceptionally suicidal for years,” he said.

“I was heavily medicated — I think I rattled when I walked. Every aspect of my life was affected.

* * *

If you or anyone you know needs help:

Lifeline on 13 11 14

Kids Helpline on 1800 551 800

MensLine Australia on 1300 789 978

Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467

Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636

Headspace on 1800 650 890

ReachOut at au.reachout.com

Care Leavers Australasia Network (CLAN) on 1800 008 774

A dream to enter the Catholic church

As a school boy Jarrod once dreamed of becoming a priest.

He met McMahon as a devout teenager with an absent father, who was keen to find a mentor on how to be a good man and Christian.

The Christian Brother took Jarrod under his wing after they met at Catholic youth events and Jarrod’s school, the former St Mark’s College in Highgate.

McMahon won his trust, and then lured him to his home, where Jarrod says the abuse took place.

Jarrod is now a firefighter in a loving same-sex relationship and close to his two sons and ex-wife.

But his hard work to process what happened to him as a 16-year-old never stops.

“Why did it take me so long? Why didn’t I deal with it then?” he said.

Jarrod was only a child when he says McMahon won his trust. Supplied

“As a young teenager I thought I was fairly worldly but nothing prepared me for the vile nature of what occurred.

“Especially as a male, just the feelings of disgust and shame and guilt. As a male, you’re not gonna tell anybody about that.”

Now an adult, Jarrod began to wonder if there were others who had been exposed to McMahon through the Catholic church, who were suffering like him.

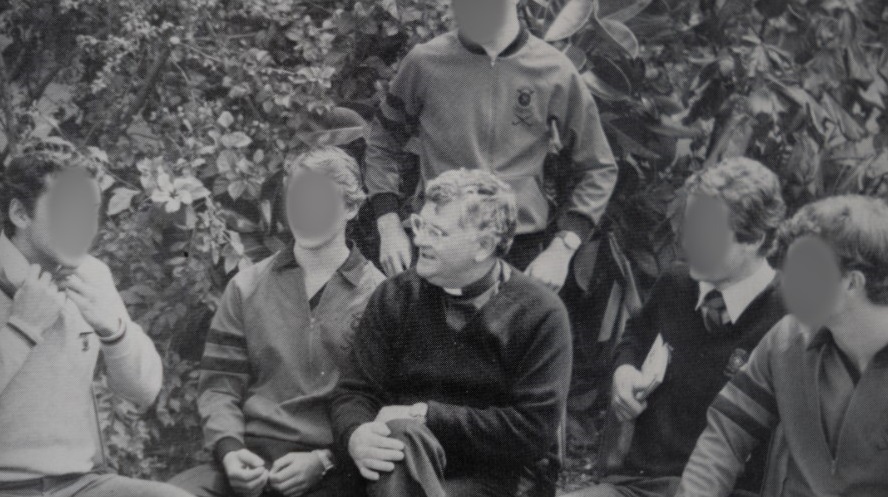

McMahon spent time at Christian Brother schools in Western Australia and South Australia during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

This included leadership positions at two of Perth’s top private boys’ schools, Aquinas and Trinity colleges — which both have sprawling campuses set on the banks of the Swan River.

From 1987 to 1989, McMahon was in charge of recruiting future priests and Christian Brothers among schoolboys throughout Western Australia

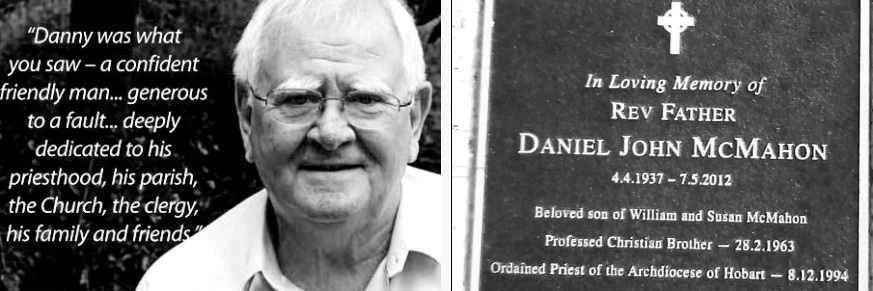

McMahon was accepted into the priesthood in Tasmania in the 1990s, going by the slightly different name of Daniel John McMahon.

Do you know more about this story? Email turner.rebecca@abc.net.au

Summoning the courage to speak out

A few weeks after his initial breakdown, Jarrod wrote to then-Archbishop of Perth Barry Hickey in July 2004, outlining how he said he was sexually assaulted at McMahon’s home in the Perth suburb of Leederville 17 years before.

He asked the Archbishop to take “immediate action” to help other survivors, past and potential.

“What if there have been others that have been abused as I was,” he wrote.

“Much damage could have occurred in 17 years due to my silence.

“This is a guilt I live with.”

The Archbishop forwarded his letter to the Professional Standards WA office, the local branch of the Catholic Church agency which handles complaints about abuse.

Church reveals Jarrod was not alone

Several months later he received a letter from the office which said the Christian Brothers had accepted his complaint about McMahon “without the need for an assessment”.

Jarrod said he was told during discussions with the office his statement was believed because of other allegations made against McMahon.

While he said the Christian Brothers were respectful and gave him a confidential payment, also agreeing to help him deal with his mounting medical bills, they did nothing with his request that they start a support group for other McMahon victims.

He said he also asked the Christian Brothers to pass his details on to any other victims, so they could get in contact if they wanted to share their experience and support each other.

“The healing is more important than the money,” he said.

“The effects are so much more encompassing — you really need that support network and a psychologist is not necessarily going to provide that.”

The devil living the good life by the deep blue sea

Frustrated by the lack of action by the Catholic Church and the Christian Brothers against a paedophile, Jarrod took it upon himself to confront McMahon in 2008.

McMahon was living in the tiny coastal township of Turner’s Beach on Tasmania’s northern coast.

Jarrod flew to Tasmania and turned up at McMahon’s door.

He says he remembers the priest getting down on bended knee, confessing and apologising.

They spoke over two days at McMahon’s home, where the priest said he had wanted to contact Jarrod but was warned off by lawyers.

McMahon said he had been interviewed by police and the Archbishop.

He didn’t know it, but Jarrod was secretly recording their conversations.

Jarrod recalls asking repeatedly if there were any other victims, but McMahon was evasive.

Even so, he recalls the priest said he had tried to keep away from young people in Tasmania because he felt he would be a predator.

Jarrod recalled felling like he was being groomed all over again, with the priest flattering him, telling him he loved him and was the only person he was close to.

But he was silent when Jarrod told him of how he had trusted him, looked up to him – and the devastating effect his abuse had had on his life.

Jarrod and his family were worried McMahon could still abuse other children.

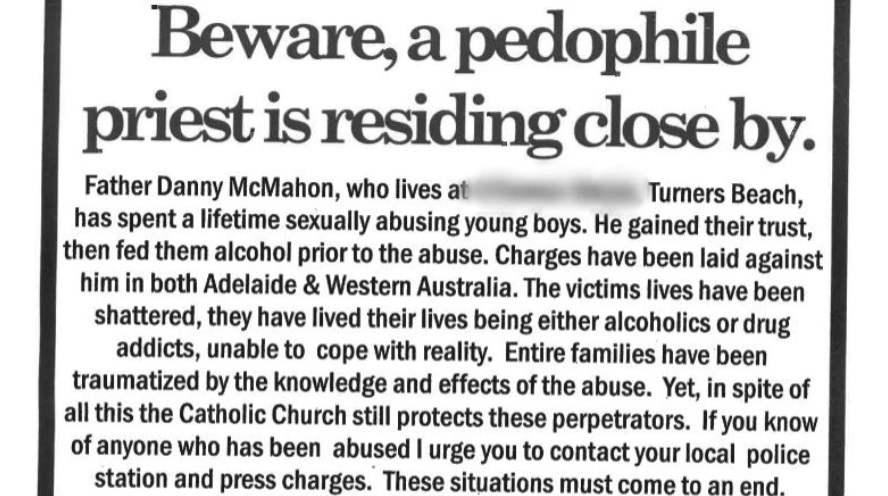

His mother travelled to McMahon’s home town from Perth and posted fliers warning of a “pedophile priest” in the area.

“I believe the police stopped her and said ‘you can’t do this’,” Jarrod said.

Secular justice too slow for man of the cloth

Three years later, Jarrod took the secretly recorded confession to WA Police.

But McMahon’s death in May 2012 ended the Luscombe family’s hope of criminal charges.

His funeral mass was celebrated by the then-Archbishop of Hobart Adrian Doyle and 18 priests at the Ulverstone church where McMahon was ordained as a priest at the ripe age of 57.

There was no mention of McMahon’s history as a violent teacher and sexual predator.

“Well done, good and faithful servant. You are a priest forever,” Br Max McAppion said in his eulogy.

How much did the church know?

The ABC has seen correspondence between a former Christian Brothers Oceania leader and one of McMahon’s former students, where the leader acknowledged they learned of allegations of sexual abuse around 1997 and 1998.

“His brutality with corporal punishment wasn’t a secret, but his sexual abuse only came to my knowledge in the late 1990s,” the email said.

“You might be aware that in 1997-98 I put out several communications, aimed at former students of our schools in WA and SA, inviting anyone who felt he had been mistreated to abused to take up one of several options.

“It was through this that I became aware of allegations against McMahon of sexual abuse.

“These were passed on to the church authority which was then responsible for him in Tasmania.”

Christian Brothers’ silence echoes beyond the grave

While behind the scenes the Christian Brothers has settled multiple compensation claims relating to McMahon, they are unwilling to talk about the reason why they have received them.

When asked by the ABC whether they acknowledged McMahon was a sex offender, the Christian Brothers Oceania declined to respond.

“The Christian Brothers do not comment publicly on the details of any settled matter and/or any matter which may be the subject of civil litigation or any legal proceeding,” they said in a statement.

The national professional standards office also declined to outline how many cases it had settled in relation to McMahon.

“I cannot comment on any cases nor can I comment or release statistics in relation to these cases,” its executive officer Shane Wall said.

The Archdiocese of Perth said it had no record of Jarrod’s letter he sent to Archbishop Hickey in 2004.

But it said it had received another complaint about McMahon in 2003, which it passed on to the Tasmanian professional standards office.

When asked whether it received any complaints from WA about McMahon, the Archdiocese of Hobart declined to comment.

It said it had received no complaints about McMahon’s conduct as a priest nor settled any claims relating to him.

Did the silence protect a paedophile while leaving children at risk?

McMahon’s frequent moves between schools has led some to question whether other complaints were made and covered up.

“The Christian Brothers do have a long and rich history of shifting paedophiles out of Western Australia when it just gets too hot,” Mr Magazanik said.

Christian Brothers records show how often McMahon shifted jobs throughout WA and SA:

1965–66 — Aquinas College, Perth

1967–68 — Christian Brothers High School Highgate, Perth (primary school principal)

1968–70 — Rostrevor College, Adelaide

1971–72 — CBC Fremantle (primary school principal)

1973–74 — St Patrick’s College, Geraldton (primary school principal)

1975–77 — Trinity College (junior school principal)

1978–83 — Aquinas College, Perth (junior school principal)

1984 — sabbatical in NSW

1985 — Thebarton, Adelaide

1986 — Thebarton, Adelaide, and Trinity College, Perth

1987–89 — in charge of vocational work for the Christian Brothers, Leederville

1990 — accepted into the priesthood by the Archdiocese of Hobart

In a 1983 Aquinas school yearbook, McMahon explained that he was leaving his position as junior school principal “for some personal development” at the request of the Christian Brothers.

“I believe it is important for a person to continue to grow and so I accepted,” he wrote to the school community.

“My year in Sydney is at an institute called “Kairos” in Dundas, the course I am doing is called ‘Towards a Spirituality for Ministry’.”

Former Aquinas geography and geology teacher Bob Stanley said people were “suspicious” when McMahon left the school and then later moved to Hobart.

Mr Stanley said he did not know McMahon was abusing children when they worked together but he knew one of his victims, who later committed suicide.

True number of victims still unknown

Jarrod now knows McMahon left behind many victims — he personally knows five — although he defines himself as a survivor.

The ABC knows of many submissions made about McMahon to the royal commission, which chose to explore the hundreds of cases of abuse at Christian Brothers children’s homes in WA between 1947 and 1968, but not McMahon.

But many of McMahon’s victims now have a fresh chance for a voice, thanks to new WA laws allowing victims to sue institutions to be sued for historical sex crimes, even if they have signed a non-disclosure agreement.

The ABC knows of at least five men, including Jarrod, preparing to sue the Christian Brothers over McMahon.

Jarrod’s lawyer Judy Courtin — who is well known for her work representing victims of childhood institutional abuse — said she believed McMahon could have more than 50 victims, likely well into their middle age.

“It’s very, very rare for a survivor or victim of childhood sex crimes to be able to disclose or talk about those crimes until they’re in their 40s, 50s, 60s, even 70s,” she said.

Jarrod’s lawyer Judy Courtin said it can take victims decades to acknowledge abuse. Four Corners

Dr Courtin cited research presented to a Victorian parliamentary inquiry into institutional abuse which indicated about five per cent of boys assaulted by Catholic clergy reported to police.

“So it’s impossible to know the true number but fifty probably at the very minimum because [McMahon] was offending, sexually assaulting children over decades,” she said.

Melbourne lawyer Michael Magazanik, who successfully prosecuted the Christian Brothers in the first case to reach judgement under the new WA laws, is also representing a victim of McMahon.

He said he had been told McMahon was a violent man who loved budgerigars.

Amid silence, men turn to each other to help

After McMahon died, media reports about his sexually predatory past at Perth schools like Aquinas and Trinity emerged.

Like many of McMahon’s former students, Dave Kelly, who went to CBC Fremantle and is now a WA government minister, was concerned some of his former schoolmates were also abused.

He knew well his former principal’s violent side because “it didn’t go on behind closed doors”, witnessed by other teachers and parents.

“I remember one day at assembly, halfway through assembly, he just stopped,” he said.

“He had rows of boys from grade 4 to grade 7 at the back. He just marched through all the boys, pushing boys aside, and grabbed a kid in year 7 and pushed him up against the tuckshop and just shook him.

“I don’t know what the kid had done but that was the sort of thing that he would do.”

Mr Kelly wrote to his old school, asking them to acknowledge its former junior school principal was an abuser and to reach out to offer support to any victims.

Frustrated with the response — or “cover-up”, as he likes to call it — from the Christian Brothers and Catholic Church about McMahon, he has used his voice as politician to call out to victims.

“I have so much admiration for the victims who have come forward,” he recently told WA Parliament.

“Their bravery is immense. As a former student, this is a sliding door moment for me; I could have been one of those students, but thankfully I was not.”

Now the McGowan government minister has found himself as the convenor of a support group for McMahon’s victims, many of whom had never come forward before he spoke out.

He has spoken to half a dozen victims, all of them middle-aged men and who attended five different Perth Christian Brother schools, who contacted him after his comments.

“They had never come forward before but they told me they’d been abused by Danny McMahon,” he said.

“It always comes as a shock but I’m not surprised because he’d abused students at every school he went to.”

Second group reaching out to past victims

Meanwhile, around Perth other groups of middle-aged former Christian Brother schoolboys had been mobilising, as they reeled from some of the horrific stories to emerge from the royal commission.

Fremantle man Damon Hurst said his group of like-minded men had been trying to reconcile the positive values they had been taught by the Christian Brothers with the widespread sexual and physical abuse at some institutions.

“Compassion is the main one and acceptance that it’s never good enough to develop your own life and your family,” he said.

“You should reach out to the dispossessed and make their life easier.”

His group designed an outreach program for WA Christian Brothers schools which would help them and religious authorities to acknowledge McMahon’s history and reach out to victims.

He said it was important to ask victims how they can help — whether they want an apology, psychological services, to take legal action or even just the acknowledgement that a terrible thing happened to them.

“You have to say ‘Hello, where are you? I’m reaching out to find you’,” he said.

“Once you’re found we say to you, ‘What can we do to help?’.”

But after presenting their ideas to the Christian Brothers Oceania and the national executive of Edmund Rice Education Australia (EREA), which governs Christian Brothers schools, Mr Hurst said it had gone no further.

Similarly frustrated, Jarrod hopes to help set up a local branch of the Survivors and Mates Support Network (SAMSN), which focuses on male survivors of clergy abuse.

Its services include professional-led peer support groups, with social workers and psychologists, and helps with issues including confused sexuality and the fear people will think they are a sexual abuser because they have been abused themselves.

After all he has been through, Jarrod is still taking it upon himself to find answers, to find “the other ones” and make sure they know they are not the only one, like he once felt.

A close up of Jarrod, wearing a red tshirt, with oak barrels behind him, looking into the camera.

“I think perhaps if there was a good support service back when I first became ill through all this, maybe my healing might have been a lot better,” he said.

“Maybe I might have been able to save my marriage, maybe my kids wouldn’t have had an emotionally distant father.

“It’s been a tough road.”

He and other men like Mr Kelly and Mr Hurst believe it is time for the Catholic institutions to step up and take over, to make sure victims receive the support they need.