(CANADA)

CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) [Toronto, Canada]

August 7, 2021

By Cameron MacLean

Researchers weigh in on apologies from premier, cabinet minister, archbishop after controversial comments

Manitobans have heard a number of apologies from public officials in recent weeks.

On Tuesday, Premier Brian Pallister said he felt sorry for the misunderstanding caused by his comments on July 7 — after protesters toppled statues of Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth at the legislature — that settlers in Canada “didn’t come here to destroy anything, they came here to build.”

On the same day as Pallister’s apology, newly appointed Indigenous Reconciliation Minister Alan Lagimodiere came out and labelled residential schools a tool of genocide, after initially defending the people who ran them.

And the archbishop of St. Boniface apologized on behalf of the Catholic Church after a priest accused residential school survivors of lying about abuse.

The public response to recent apologies from Manitoba political and religious figures has varied. Judging the value of an apology often depends as much on what comes after as the words themselves, said Brandon University political science professor Kelly Saunders.

“You want some kind of reconciliation,” she said. “You need to repair that relationship, that breach. And so that’s more than just saying ‘I’m sorry,’ that is making amends.”

3 main components

A good apology has three main components, according to Neil McArthur, director of the Centre for Professional and Applied Ethics at the University of Manitoba.

“We want to feel like the apology is going to actually lead to some kind of change,” he said.

That means that first, the individual must show they understand why something they did was wrong or caused harm. They must then take responsibility for actually having done the thing they are apologizing for.

Finally, the person must commit to follow up their apology with some kind of concrete action.

By those standards, Pallister’s apology at a news conference earlier this week may fall short, said Molly Howes, a clinical psychologist based in Boston and the author of the book A Good Apology: Four Steps to Making It Right.

“I feel awful about the reaction and the misunderstanding I created with my comments,” Pallster said.

He then said he was trying to pay tribute to the people — Indigenous and non-Indigenous — who’ve built families and communities in Canada.

Pallister’s apology fails because it focuses on the reaction of others rather than his own words, Howes said.

“It’s sort of blaming somebody else for misunderstanding,” she said.

It also fails because he waited nearly a month after his original comments to offer an apology, and then followed it up by a defence of his original intentions, said Saunders.

“A meaningful apology has to be sincere. It can’t be equivocal.”

Indigenous leaders responding to Pallister’s apology indicate they share that assessment.

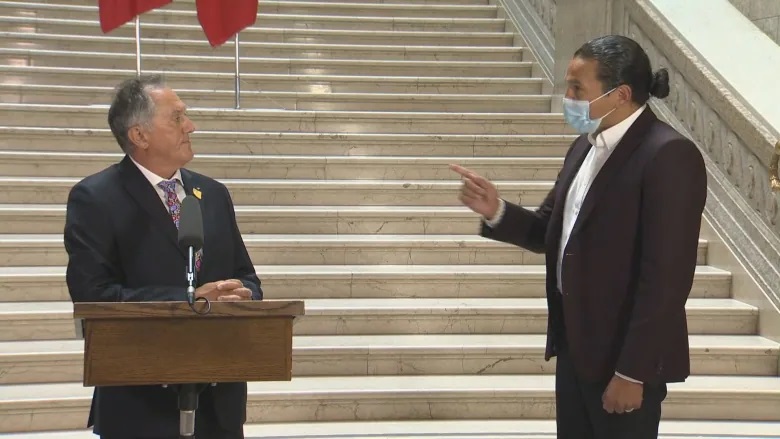

“I would actually expect a better apology than saying, ‘Sorry, I was misrepresented.’ That’s not really an apology,” said Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs Grand Chief Arlen Dumas.

Political conundrum

By contrast, Saunders said Lagimodiere’s apology and subsequent actions have been more meaningful.

On Wednesday, Lagimodiere repeated sentiments he first expressed the day before, saying the residential school system “wasn’t just cultural genocide.”

The plan of Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, “was to eliminate Indigenous people from Canada. And that, to me, is genocide,” he said.

After the outcry following his original statements, which suggested residential schools were started with good intentions, Lagimodiere said he would reach out to Indigenous leaders in Manitoba in an effort to repair the damage his words had caused.

“He’s committed to working and listening to Indigenous leaders and elders and trying to learn from them and not repeat the same mistakes,” she said.

Lagimodiere faces a conundrum, however, as a politician attempting to make amends, said McArthur.

“I think the issue of sincerity will arise, because it does seem like he’s only motivated to make those statements because of the criticism he’s received,” he said.

“So I think that his future statements and his future actions will probably be judged in that context.”

Better examples

Of the three high-profile public apologies in Manitoba in recent weeks, the one from Archbishop Albert LeGatt may have been the best, said Saunders.

LeGatt apologized after a sermon by St. Boniface priest Rhéal Forest, in which he accused residential school survivors of lying about being sexually abused to receive more money in settlements with the federal government.

“I wish to say very, very clearly I, and I hope more and more people, come to that place of completely disavowing that kind of thinking,” LeGatt said, describing Forest’s comments as “racism.”

Speaking as forcefully as LeGatt did took courage, Saunders said.

“We know that the Catholic Church as an institution has not been as perhaps apologetic and forthcoming on this issue as they should be.”

Leaders in other countries around the world have shown what meaningful apologies can look like, Howes said.

Last Sunday, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern participated in a ceremony with members of the Pacific Island community. The ceremony formed part of an apology for a crackdown by the New Zealand government that targeted Pasifika people for deportation starting in the mid-1970s.

[New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, centre, is covered during a ceremony in Auckland on Sunday, Aug. 1, to formally apologize for a racially charged part of the nation’s history known as the Dawn Raids, when the Pasifika people were targeted for deportation during aggressive home raids by authorities. (Brett Phibbs/New Zealand Herald via AP)]

The government of Germany recently acknowledged a genocide committed in Namibia, beginning in 1904, in what was then known as German South West Africa.

The ultimate test of an apology, Howes said, is whether or not the individual repeats the mistake — and Manitobans will have to wait to see how public officials meet that test.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Cameron MacLean is a journalist living in Winnipeg, where he was born and raised. He has more than a decade of experience covering news in the city and across the province, working in print, radio, television and online.

With files from The Associated Press