TEL AVIV-YAFO (ISRAEL)

Forward [New York NY]

July 8, 2021

By Yardena Schwartz

The story is all too familiar. A child is sexually assaulted and the perpetrator either goes unpunished or gets a short prison sentence, even community service.

Activists describe a vicious cycle in which victims and their families have such low expectations of the Israeli justice system’s response that victims do not even report incidents — creating a public sense that child sexual abuse is not much of a problem.

But the Office of the State Attorney and groups dedicated to addressing the problem estimate that there are in fact tens of thousands of child sexual abuse cases in the country annually, many of them difficult to prosecute because there are no eyewitnesses and because the victims are young and traumatized.

After a series of particularly egregious cases resulting in limited consequences, advocates intensified public campaigns this spring and notched several small victories that they hope are harbingers for a broader change.

- Avraham Leshem, 24, who admitted to sexually assaulting a 4-year-old girl, was scheduled to be released after serving part of a three-and-a-half year sentence. But in April — after mounting a public campaign — the girl’s parents were able to convince the state attorney’s office to appeal the verdict to Israel’s Supreme Court. A hearing of that appeal is scheduled for December.

- Yarin Sherf, 21, was indicted in March for “forbidden consensual relations” with a 13-year-old girl at a hotel where people were quarantined during the pandemic under the auspices of the welfare ministry. According to the indictment, Sherf told the girl to come to his room, threatening her that if she did not, he would carry out an “Eilat 2.0,” a reference to the gang rape of a 16-year-old girl in an Eilat hotel last summer. Following public outcry, the state attorney’s office added rape to the charges.

- Eviatar Gross, a teacher, was sentenced to community service last September for committing indecent acts on an 8-year-old student at school. The acts included Gross showing his penis to the student, asking her to touch it, and then instructing her to show him her vagina. During a retrial in late March, Gross was sentenced to 20 months in prison.

While these three cases suggest progress, advocates say more needs to be done to reduce child sexual abuse. They want the Israeli government to establish a public sex-offender registry, and to create a special department within the court system to handle violent crimes involving children.

“The Israeli public still looks at child abuse as something that happens to others,” said Anat Ofir, director of the Child Abuse Prevention Initiative at the Haruv Institute, which launched a media campaign five years ago to raise awareness of the issue.

“When the Israeli public and decision-makers do not see this as an epidemic, no less than COVID, the courts get away with horrible decisions,” she said. “I think child abuse is waiting for a big social movement to raise awareness of this issue so we can make changes to the law system, the judicial system, and social services.”

Several families who have taken their children’s cases to court agreed to speak to the Forward in hopes that more people would understand their frustrations, and to eliminate the stigma that prevents many parents from speaking out. Some requested anonymity to protect their children’s privacy.

A preschooler’s nightmare

The Leshem case happened just after Purim 2019, outside a synagogue where the 4-year-old had gone to Shabbat services with her father and brother. She encountered Leshem, whom she did not know, when she went out to play in the yard, according to the indictment. He lifted her up, hugged her, set her down, and laid on top of her. With one hand, he took out his penis and began to masturbate, the girl told her parents and the police; with the other, he inserted his fingers inside her vagina.

Immediately after the incident, the girl’s parents informed the police and gave them the girl’s dress, which was stained with semen.

“It hurt so much I wanted to scream,” she told police investigators.

With DNA evidence from the dress, police were able to quickly arrest Leshem, who was in their database. Two years earlier, he had been under investigation for sexually assaulting a boy, though charges were never filed.

A month after the attack, state prosecutors indicted Leshem, charging him with rape and indecent assault. The parents described a tortuous process for their daughter, who was questioned for 45 minutes by a police investigator on every detail of the assault. The girl’s parents thought the ordeal was worth it. They believed Leshem would receive the punishment he deserved, preventing him from abusing other children.

But last September, Leshem was acquitted of rape; he was convicted of “indecent acts,” for which the maximum penalty is 10 years in prison. He was sentenced on March 16 to three and a half years, but was originally slated to be released as early as August.

“This is the absurdity of justice in Israel,” the girl’s father said in an interview in March. “The courts are doing more to protect abusers than our children.”

The father said his daughter, now 7, continues to suffer: She began wetting her bed soon after the attack. She often wakes up at night screaming, and frequently needs to sleep in her parents’ bed. She has been seeing a therapist weekly.

The case exemplifies the challenges surrounding such prosecutions. Indeed, according to activists, the fact that the case even made it to trial was a rare achievement: most don’t.

Leron Eshel, a lawyer and social worker who leads the Child Victim Assistance Center at the National Council for the Child, said the decision of whether to have a child victim testify in court is generally made by the police department’s child investigator, who is also a social worker.

“There are times, when the child investigator forbids children from testifying in court because they are afraid of how it will affect [the child], or because they do not deem [the child’s] testimony reliable; then there is not enough evidence to be heard in court, and the case is closed,” Eshel explained. “Today, there is more awareness of this problem and we are seeing more and more interrogators allowing children as young as 9 to testify in court.”

In the Leshem case, Eshel said, the investigator deemed the girl’s testimony reliable, but thought her age and condition made testifying a bad idea. Instead, the investigator’s notes from her taped testimony were submitted into the record.

In its appeal of the verdict, filed on April 28, the State Attorney’s Office seeks anew to convict Leshem of the offenses of rape and indecent act on a minor in aggravated circumstances, and to lengthen Leshem’s sentence considerably.

“The district court found the girl’s testimony credible, and ruled that the girl had experienced the things she described in her testimony,” they wrote in the appeal. “The girl testified to experiencing the act of rape. Leshem chose not to testify in his defense and did not provide a version that explains or deals with the girl’s testimony.”

Leshem’s lawyer, Leron Malka, said that her client admitted that he had touched the girl’s genitals, but had not put his finger inside her vagina. “There is no evidence for rape,” Malka said.

Malka also filed a separate appeal of the verdict, arguing that her client is mentally ill and thus should not serve any time in prison. A hearing on both appeals is scheduled for Dec. 2. “He is not a criminal — he is dangerous because of his illness,” Malka said in an interview. “He who suffers from illness does not go to jail. In jail there is no treatment for him.”

A global — and Israeli — problem

Israel is hardly unique in failing to bring those who sexually abuse children to justice.

The scandal that Boston Globe reporters uncovered in the Archdiocese of Boston nearly two decades ago, in which abusive priests were routinely reassigned to parishes only to abuse children again, led to similar discoveries around the world. A British inquiry launched in 2014 documented thousands of cases of abuse in English and Welsh schools and religious institutions. In France, the law was only changed this year to make sex with a child under 15 automatically considered rape.

Ofir, of the Haruv Institute, said sexual abuse of children in Israel is no more prevalent than it is in the United States or Europe.

“One in five children in Israel, as in the U.S., experience sexual abuse,” she said. The difference, she added, is the disproportionately light sentences imposed in Israel.

Ofir and other Israelis who counsel victims of these crimes and their families said there is much more the judicial system could do to better prosecute the perpetrators and to protect the innocent.

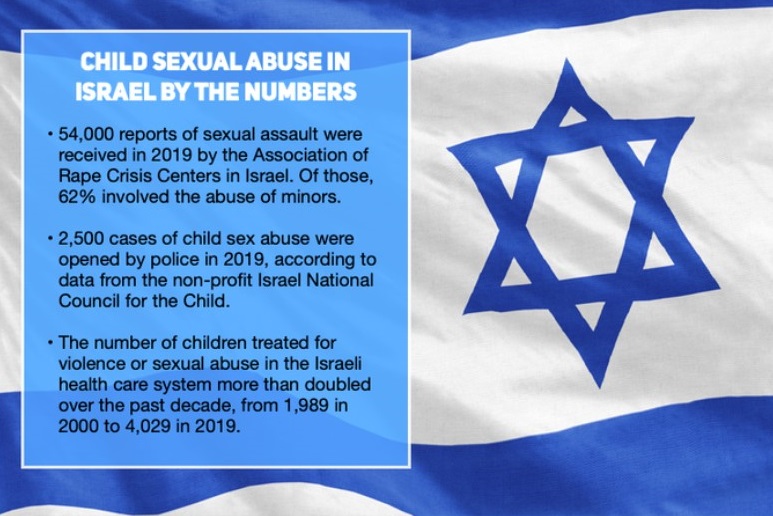

In 2019, some 54,000 reports of sexual assault were received by Israel’s Association of Rape Crisis Centers; 62% of them, or 33,480, involved minors. Yet the number of child sexual abuse cases opened that year by the police was about 2,500, according to Eshel’s organization, the National Council for the Child.

“What is reported to the authorities is just the tip of the iceberg,” Eshel explained. “Much of the abuse is never reported by parents. Many children are afraid to tell anyone about it. Sometimes they don’t understand that what they experienced was a crime.”

She lamented that even when child sexual abuse cases are prosecuted, they seem to be taken less seriously than a host of other crimes. “Someone who committed a financial crime can sit behind bars, while someone who raped a child can serve community service,” she said. “In the United States, it is very unlikely that a teacher who sexually abuses a student would be sentenced to community service.”

Though advocates are gratified by successful pushes of Israeli authorities to revisit a few recent cases, and in some, impose heavier penalties on the perpetrators, many advocates said that most people accused of these crimes end up going free.

They pointed to a 2020 gang rape of a 9-year-old girl by four boys, the eldest of whom was 14. All four accused denied involvement and were eventually released; the girl’s mother complained to friends that uniformed police officers came to question the victim at night, traumatizing her more, according to a report in the Times of Israel.

A ‘broken’ system

Eshel and other experts working to change the system say obstacles include the reluctance of the courts to hear children’s testimony, judges’ tendency to issue light sentences, and the lack of irrefutable evidence in many cases.

Ofir and other advocates said child victims almost never testify in Israeli courts. The conventional belief is that children’s privacy should be protected, and that putting a child on the stand for questioning can be emotionally damaging — a risk most parents choose not to take.

And even when victims do take the stand, it’s difficult to present corroborating evidence or witnesses, since most sexual assaults happen when a child is separated from others.

Without hearing from a child, judges may have more compassion for the defendant, Ofir and other advocates for child victims contend, and this partly explains why the punishment for child sex abuse in Israel is lighter compared to other crimes, including property offenses.

Compounding the problem, activists say, is that even once offenders are convicted, incarcerated people are often released early due to overcrowding. “We have tried to appeal to the Knesset to change this law to prevent the release of sex offenders,” Eshel said, referring to a law known as “nikui shlish,” which allows early release for good behavior.

Yael Sherer, director of the Survivors of Sexual Violence Advocacy Group, said she knows firsthand how broken the system is. Her own father sexually abused her throughout her early childhood, Sherer said; after years of legal battles, he was eventually sentenced to three years in prison, and discharged for good behavior after two.

“Israeli judges,” she sighed, “are very forgiving.”

These advocates say that after years of acquittals and light sentences, victims and their families are loath to come forward.

“Say a mother discovers her child was sexually abused, and then she hears the story of Avraham Leshem,” said Ofir. “She’ll say, ‘why should we go through this torture if this is how it’s going to end?’ It’s this snowball that keeps rolling.”

One such mother who wishes she had never reported what happened to her daughter said the system was stacked against the girl, who was 16 when she was sexually abused at school by her 38-year-old teacher, Ori Gilad.

Gilad was convicted in 2019 of indecent acts and sentenced to seven months of community service. Gilad’s lawyer argued that his sexual relationship with his student was consensual. One of those who testified on Gilad’s behalf was from the Ministry of Education, which particularly infuriated the victim’s mother, who wondered why anyone would defend a teacher who had admitted to having sexual relations with a student.

“We were put through torture only to see him move on with his life while we are stuck in a nightmare,” said the mother. “It wasn’t worth it.”

A spokesperson for the Israeli court system declined to comment on any specific case, or the general issue of child sex abuse, given they are actively adjudicating such cases.

Court records for these cases are often kept confidential by the state or heavily redacted, due to the victims’ ages and the sensitive nature of the accusations. The parents of Leshem’s victim, for example, said they have not received a copy of their daughter’s testimony.

Demanding change

Numerous Israeli nonprofits have been working to assist victims and their families. The National Council for the Child offers a free service in which volunteers have escorted more than 4,000 children and families through the legal process to, as Eshel put it, “minimize as much as possible the secondary victimhood.”

The organization is also pushing for appeals in cases of very lenient punishments, Eshel said, “so that a higher level court will address the issue and hopefully set a stronger sentence, and then that can be relied on in the future to change the cycle we are in.”

Activists have also been lobbying Knesset members for years to try and establish departments within criminal courts that would exclusively handle cases involving child victims of violent crimes. They said they have gotten a bit more traction lately with lawmakers on the issue.

“In these departments,” said Eshel, “all judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys will be trained on the needs and interests of child victims.”

But some advocates say significant change won’t happen without pressure from the public. That’s why the parents of Leshem’s victim embarked on a public-awareness campaign, speaking to media, leading protests, and creating a fundraiser to support the cause.

They now plan to establish a new nonprofit to help parents in similar cases navigate the legal system.

“In our case, we have a strong, supportive community and we know the world of social workers and therapists,” said the father, who has worked with at-risk youth in Jerusalem for years. “Most people don’t have that support.”

The couple began demanding an appeal of Leshem’s sentence as soon as it was handed down. Both the state’s appeal, and the appeal filed by Leshem’s attorney, will be heard in the same Jerusalem court, by a different set of judges, in December. The parents are gratified to at least have another chance.

“Trust me,” said the girl’s father. “We’d love to crawl back into our cocoon and disappear into our privacy. But when you hear that somebody is doing this over and over again, you can’t just sit there and be quiet.”

Yardena Schwartz is a freelance journalist based in Tel Aviv and Europe. Email: yardena.schwartz@gmail.com.