ALBANY (NY)

Times Union [Albany NY]

July 31, 2021

By Edward McKinley

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany engaged in a decades-long cover-up of chronic child sexual abuse committed by its priests, according to a statement by former Bishop Howard J. Hubbard, who ran the diocese from 1977 to 2014.

Hubbard’s statement, issued through his attorney in response to a series of questions from the Times Union, confirmed that the diocese shielded priests and others facing sexual abuse allegations — sending them into private treatment programs rather than contacting law enforcement officials. Some of those priests allegedly emerged from treatment and committed more crimes.

“When an allegation of sexual misconduct against a priest was received in the 1970s and 1980s, the common practice in the Albany diocese and elsewhere was to remove the priest from ministry temporarily and send him for counseling and treatment,” Hubbard said. “Only when a licensed psychologist or psychiatrist determined the priest was capable of returning to ministry without reoffending did we consider placing the priest back in ministry. The professional advice we received was well-intended but flawed, and I deeply regret that we followed it.”

Hubbard’s response comes as he is facing multiple allegations of sexually abusing a minor, and is named in dozens of additional court cases in which he stands accused of covering up abuse by others.

The bishop’s acknowledgement comes as there have been roughly 300 Child Victims Act lawsuits filed against the Albany diocese, providing an unprecedented window into the organization’s documented history of abuse, as well as the actions of Hubbard.

The cases name hundreds of predators and describe decades of abuse allegedly committed by priests and others who preyed on the children in their care, while using their positions to evade accountability.

For this story, the Times Union reviewed thousands of pages of court records, including once-secret documents kept by the diocese, and interviewed attorneys, survivors and experts on child abuse.

The information confirmed a pattern in which abuse claims may have been ignored or abusive priests shuffled into treatment and back into ministry rather than being reported to police.

One such case unfolded around 1983, when Eileen Thompson received a tearful phone call from her teenaged nephew.

He said he’d been molested by Gerald Miller, a priest from Altamont, and didn’t know what to do. He’d confided with another adult at his school, but that person had told him, “Well, after what happened to you, you’re never going to be a real man.”

He couldn’t stop crying during the phone call, Thompson recalled.

The details of her account are outlined in a deposition before attorneys for the Albany diocese and for Hubbard as part of a lawsuit claiming negligence over a separate sexual abuse allegation. In the deposition, Thompson (whose name was changed for this article to protect her identity) testified under oath.

“How can I help you? What can I do for you?” Thompson recalled telling her nephew.

“I have to go. I’ll call you,” she remembered him saying before he hung up. She expected him to call back to finish their conversation, or maybe drop by her home to see her, which he did frequently.

Instead, the next day he went to his uncle’s house in Rensselaerville and killed himself with a shotgun.

An attorney who has handled thousands of abuse cases against the church nationally said that the body of evidence suggests Albany was a “problem diocese,” as both Hubbard and his former second in command, Edward Pratt, both stand accused of abuse.

Thompson was “almost hysterical” at her nephew’s funeral service. She heard someone mention in passing that Miller was supposed to officiate, since he was so close with the deceased, but ultimately hadn’t for some reason. A few weeks later, Thompson called the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany and asked to speak with the bishop.

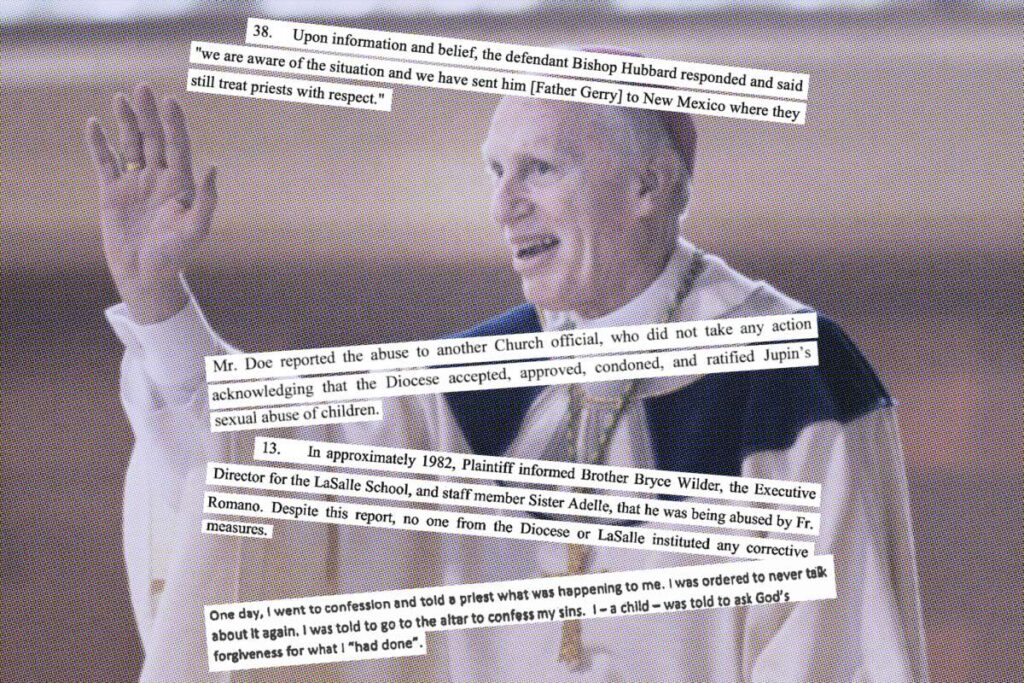

A man picked up the phone and said he was the bishop. Thompson told him about the call she received from her nephew and what he said Miller had done to him. She asked if the bishop knew about the situation. Hubbard told her he was aware of it, she said, and the words he allegedly said next Thompson was able to recall exactly — nearly 40 years later — because she was so shaken by them that she stopped going to church.

“Father Gerry is being sent to New Mexico where they have more respect for priests,” Thompson said Hubbard told her. New Mexico is the home of a now-infamous treatment site where abusive priests from around the country were sent.

In his detailed response to the Times Union, Hubbard said he was a leader in the church on fighting abuse and had championed policies such as background checks and compensation funds to redress the church’s legacy of sexual abuse. He denied that he ever brushed aside abuse. His statement was not sanctioned by the diocese.

Hubbard’s description of his role stands in contrast with allegations leveled against him in court records and available documents. A number of plaintiffs, including Thompson, say they personally informed Hubbard of abuse only to be ignored or intimidated to remain silent.

Jeff Anderson, an attorney with one of the largest abuse firms in the country, compared Hubbard to former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick. A former powerful figure in the American Catholic church, McCarrick was defrocked due to allegations of child abuse, and on Friday was charged with sex crimes against a 16-year-old boy in the 1970s.

Hubbard “was able to protect himself and all of his priests at the same time, doing the same things that McCarrick did. As an offender and also as someone who was in complete control over all the clerics,” Anderson said. “He was able to protect himself without accountability to anybody, to protect so many offenders. So many kids and so many months, years and decades.”

‘I was ordered to never talk about it again’

The court records reviewed by the Times Union describe a period of decades in the Albany diocese in which various priests or employees were accused of abuse and the diocese or Hubbard were alerted to the allegations.

Yet many of those who came forward say they were often ignored.

In one case, a lawsuit accuses a priest of sexually abusing a boy at a Catholic school in 1969. When the boy told the executive director about it, nothing was done. In 1972, another lawsuit claims, another young boy informed a priest in confession that a priest had sexually violated him, and again, apparently nothing was done.

In a 1982 incident, according to another claim, a man contends he was sexually abused as a boy by the Rev. Joseph Romano — now listed on the diocese’s list of credibly accused priests and the most frequent alleged predator in Albany CVA cases — at the LaSalle School in Albany. The boy informed the director of the school, the lawsuit says; nothing was done, and Romano allegedly continued to abuse the boy.

Michael Harmon, who is suing the diocese, says he was abused in the 1980s by Pratt, who was vice chancellor of the diocese, often inside the chancery in a room across the hall from where Hubbard lived.

Harmon said that while Hubbard never abused him, the bishop was aware that the boy would spend multiple nights each week in Pratt’s bedroom at the chancery.

After years of alleged abuse, on a day when Pratt was downstairs in the chancery, Harmon said he told Hubbard what had been happening and asked for his help. In response, he said, Hubbard told him to leave the chancery immediately and never tell anyone what he had just said or that he would be arrested. Hubbard categorically denies Harmon’s allegations and says that no guests ever stayed in the priests’ quarters at the chancery.

In a letter sent to Hubbard in 2011, another man who identifies himself as a survivor of sexual abuse at the hands of an Albany Diocese clergyman described going to confession and telling a priest about the abuse he was suffering. “I was ordered to never talk about it again, I was told to go to the altar to confess my sins,” he wrote. “I — a child — was told to ask God’s forgiveness for what I ‘had done.’”

If the claims weren’t ignored or the priest admitted to abuse, the diocese’s policy for many years was to send priests to treatment. They wouldn’t report the abuse to the police, avoiding both public scandal and accountability.

‘Low risk … provided there is proper follow-up’

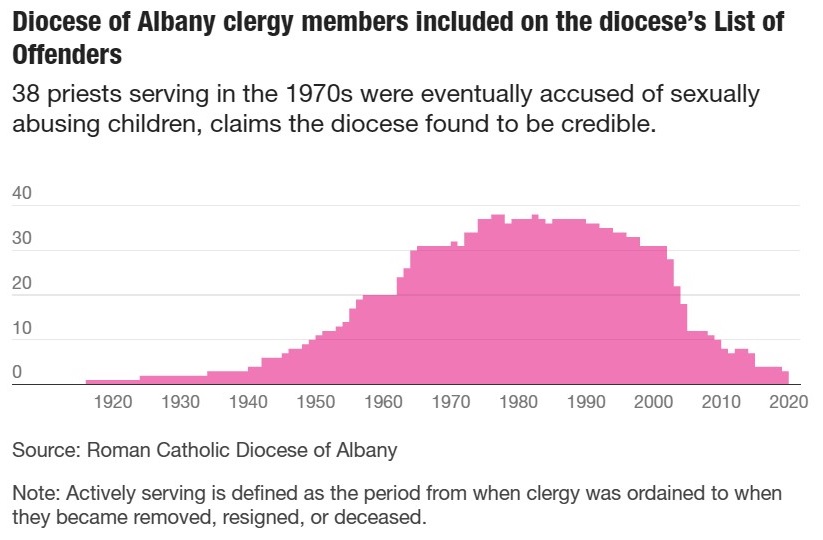

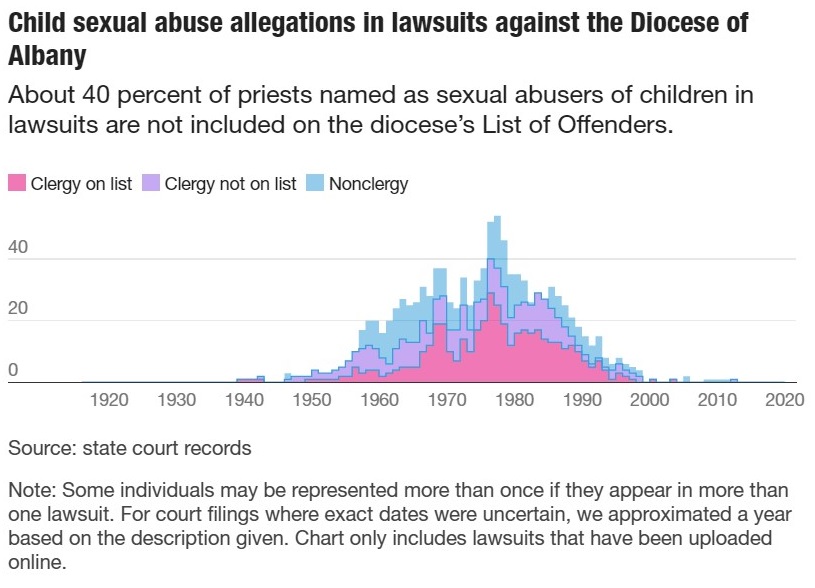

There are 189 individuals accused of sexually abusing children in the CVA cases filed against the diocese, according to a Times Union analysis. Those lawsuits contain about 343 separate allegations of sexual abuse.

The Albany Diocese published its “List of Offenders” in 2015 identifying priests credibly accused of sexual abuse. It now has dozens of names, with new ones added as recently as last year.

Not all of the alleged perpetrators are priests; the records indicate about 22 percent of the cases are against nuns, school janitors or teachers. Some of the perpetrators are unnamed.

Of the 264 CVA allegations involving priests, 58 percent are included on the diocese’s List of Offenders and 42 percent are not. Of the priests with the most individual claims against them, the top 11 are all included on the list.

In 2002, the extent of the epidemic of chronic sexual abuse of children by Catholic priests were thrust on the national stage due to the Boston Globe’s award-winning Spotlight series on abusive priests. That summer, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops convened a meeting in Dallas and adopted a zero-tolerance policy for priests credibly accused of abusing children.

Hubbard led the charge against the policy as written, arguing that allegations of abuse by priests should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. He compared the zero-tolerance policy to Gov. Nelson Rockefeller’s mandatory-sentencing drug laws in New York, saying they were harmful. After his amendment failed, Hubbard ended up supporting the policy in the final vote.

“We as a society now better understand the often compulsive nature of the sexual abuse of minors and the profound traumatic harm such abuse inflicts upon them. I regret that I did not have this appreciation sooner,” Hubbard said recently.

Less than a month after that 2002 meeting in Dallas, the Albany Diocese removed six priests — including Pratt.

When the priests were removed, The Albany Diocese told The New York Times that it had only learned of abuse allegations against Pratt “in recent weeks.”

But court records call that assertion into question.

In 1999, Pratt was sent by Hubbard for psychological treatment to the Southdown Institute in Ontario, Canada, records obtained by the Times Union show — including memorandums sent directly to Hubbard. Pratt’s treatment was related to allegations of sexual misconduct that had occurred 16 years earlier, the memos reveal.

In treatment, Pratt openly discussed his difficulties restraining himself from “sexually acting out” and “acting out with youth,” according to a physician’s summary of his treatment that was sent to Hubbard.

The doctor wrote that Pratt may be depressed, that his treatment had reached “an impasse,” that Pratt expressed feelings of “stuckness” and “hopelessness,” and that “some important issues remain unresolved.”

But ultimately, the doctor recommended that Pratt return to the ministry: “Ed is considered to be at a low risk for acting out at this time, provided there is proper follow-up.” Pratt was allowed to return to Corpus Christi Church in Clifton Park.

According to another CVA lawsuit, Pratt allegedly sexually abused a 10-year-old altar boy a year later in the bathroom of Corpus Christi on two occasions, traumatizing him for life.

Hubbard’s attorney contends the diocese had recently received an additional complaint against Pratt, although he was removed due to the previous abuse he’d admitted to and attended treatment for that.

The diocese’s leadership neglected to share that distinction publicly at the time, instead making it appear as though they’d only recently learned of Pratt’s alleged abuse for the first time.

“While we cannot offer detailed information on historic events that occurred long before Bishop (Edward) Scharfenberger arrived in the diocese, we can with absolute conviction say that the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany takes all allegations of abuse seriously and remains committed to uncovering the truth without fear or favor,” the diocese’s spokeswoman, Mary DeTurris Poust, said in a statement to the Times Union. “Our first concern is for survivors. We stand ready to accompany them, support them, and assist them, and we commend them for their bravery in coming forward.”

The diocese has provided about $10 million in financial compensation to roughly 100 survivors of sexual abuse, Poust said, and it continues to do so “on a case-by-case-basis.” Poust also stressed that the diocese has since 2002 conducted 38,381 background checks on staff and volunteers and required 37,900 safety trainings.

Hubbard’s sealed deposition

Hubbard was deposed in recent months by a group of lawyers who have filed cases against him, according to court records. But his sworn testimony — in which he would have answered detailed questions about the abuse allegations he faces and his handling of other sexual abuse claims — remains sealed by a court order.

Attorneys for many of the alleged victims said they are seeking to prove that the diocese’s practices enabled abuse. They’re seeking personnel files from all accused priests, not just the ones who allegedly abused their clients; the diocese is fighting that request in court. But an appellate judge recently ruled that the diocese must turn over the records in the coming weeks, although a protective order will keep them under seal unless cases go to trial.

After the alleged 1983 conversation between Thompson and Hubbard, Miller was not sent to New Mexico, the diocese’s lawyer noted during Thompson’sdeposition. Miller instead continued to operate an unlicensed home in Altamont where troubled boys lived with him through private arrangements with their parents.

In 1987, two boys who were living with Miller came forward and said he had been sexually abusing them for two years. Miller was investigated by Child Protective Services and by the police, and Hubbard was informed of the allegations. Miller was a religious order priest and not under Hubbard’s direct supervision.

“Prior to 1987, I was unaware that Father Miller was conducting a residence for boys,” Hubbard said. “When I learned of the situation, I immediately contacted Father Miller’s provincial and confronted Father Miller himself, ordered the children placed in another facility, and barred Father Miller from interacting with children until an investigation by Child Protective Services was completed.”

Hubbard did, however, have the diocese set up a meeting with Miller in 1987 and gave him various disciplinary instructions. The priest admitted to Hubbard that he’d physically struck one of the children in his care, and had allowed another to sleep in his bed. He denied sexually abusing them.

Still, Miller is not included on the Albany diocese’s list of credibly accused priests. A spokeswoman for the diocese said he would be added to the diocese’s list “if and when” he was added to his own religious order’s parallel list. There are two CVA lawsuits naming Miller as an abuser, as well as a third that targets “Father Miller” but doesn’t include a first name.

Hubbard provided a memo — also available in court records — that he wrote in 1987 that says the children in Miller’s care should be taken from his home and that he wouldn’t be allowed to supervise children while under investigation.

That same memo, however, goes on to say that Miller would be allowed to teach a teen seminar, as planned, that very day, with Hubbard noting that other adults would be present to supervise. It does not say whether those adults were informed of the abuse allegations against the priest.

At the end of that memo, Hubbard mentions that he’d recommended an attorney to represent Miller.

In a second court document, Albany attorney Michael Costello identified himself as Miller’s lawyer in a 1987 letter to the state child abuse agency. Costello has for decades been a lead attorney for the Albany diocese on sexual abuse and other matters, and also represents the diocese them in the pending CVA cases.

Costello was also one of the attorneys who questioned Thompson in her recent deposition.

Edward McKinley reports on New York state government and politics for the Times Union. He is a 2019 graduate of the Missouri School of Journalism and a 2020 graduate of Georgetown’s Master’s in American Government program. He previously reported for The Kansas City Star newspaper, and he originally hails from the great state of Minnesota. You can reach him at Edward.McKinley@timesunion.com.