CHICAGO (IL)

Chicago Sun-Times [Chicago IL]

June 18, 2021

By Robert Herguth

Some religious orders have balked at posting lists of predator priests. But the Claretians’ U.S. websites don’t even mention the scandal, how they’ve responded or how victims can complain.

Among Catholic religious orders in the United States that, like the U.S. church itself, are facing a national reckoning over clergy sexual abuse of children, the Claretians stand out.

The Claretians operate Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, 3200 E. 91st St. on the Southeast Side, which was the first Mexican American Catholic congregation in Chicago, established in the 1920s. Many of the order’s ministries center on children, including tutoring, violence prevention and arts programs.

Like other orders that operate in the Chicago area, the Claretians have faced abuse allegations. Six clerics accused of sexual abuse have served at some point at Our Lady of Guadalupe, records show.

Some male religious orders have heeded calls by Cardinal Blase Cupich and others to post public lists online of their members who have been credibly accused of child sexual abuse. Others say they are considering doing so.

Even among orders that do not, many still post information online on efforts to prevent abuse and where victims of abuse can turn for help and to report what happened to them.

Not the Claretians. In stark contrast to other Catholic religious orders, they do not even mention on their websites the decades-old abuse scandal that the church in the United States continues to be shaken by or how they have responded to it.

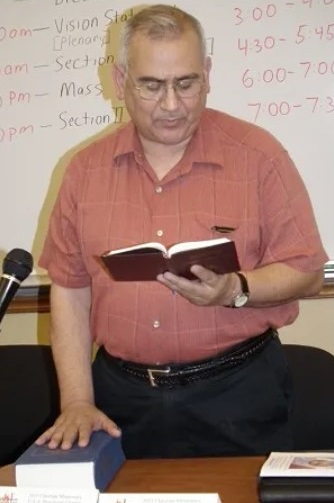

“It’s like they don’t care,” says Hank Estrada, a onetime Claretian seminarian.

Estrada left the order in the 1980s. He says that was after he was groomed for sexual contact as a young adult by his superior and then sexually abused.

“It’s like ‘out of sight, out of mind,’ ” Estrada, now 65 and living in New Mexico and who wrote about his experiences with the Claretians in a memoir, says of the order.

The order has faced high-profile accusations of clerical abuse and was accused eight years ago by a national victims advocacy group of trying to bury its problems with one Claretian brother by shipping him to Africa and South America. That was after the order faced a “credible” child sexual misconduct accusation against him in the United States.

Barbara Blaine, the now-deceased leader of the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, or SNAP, said then, in 2013: “The Claretians are knowingly putting kids in harm’s way and breaking every pledge Catholic officials have made for more than a decade about openness and children’s safety.”

SNAP called on the order — which has its U.S. headquarters and oversees a shrine in Chicago — to “permanently post the names of offenders on church websites.”

Eight years later, the Claretians have not done so despite similar calls by other church reform activists and by bishops including Cupich, Chicago’s top Catholic cleric.

The head of the Claretians’ American province, the Rev. Rosendo Urrabazo — who lives in Oak Park with other members of the order — and the order’s longtime Chicago attorney did not respond to interview requests about how they are dealing with child safety and predator priests, including whether they have adopted rules on when, how and where clerics are allowed to interact with minors, as many Catholic orders have done in recent years.

Also unanswered:

- Do they submit to regular child-safety audits to gauge how well members are adhering to any reforms that have been adopted in the wake of three major waves of priest sex abuse scandals in the United States dating to the 1980s?

- Are their clerics with credible allegations of sexual abuse restricted or monitored in any way in an effort to ensure they’re kept away from the public or children?

According to court records, attorney files and interviews, more than 20 Claretian priests and brothers have faced sexual abuse accusations,including six who served at Our Lady of Guadalupe.

“That is their ground zero,” attorney Marc Pearlman, who has sued the Claretians on behalf of clients, says of the Southeast Side church. “That’s the equivalent of their cathedral.”

Some of the reported incidents involving Claretian clergy members date back more than 50 years, but many surfaced only in recent years.

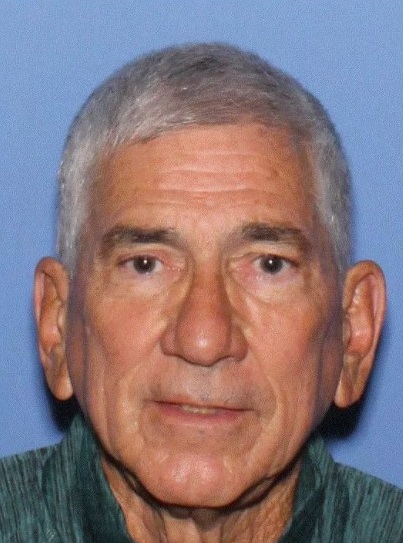

Lawrence Lovell is among the Claretian clerics who have been accused of abuse. Lovell, a former Claretian priest who lived in the Chicago area in the late 1980s, recently was released from an Arizona prison after serving more than 15 years for child sex crimes while serving as a priest.

The order also faced a Cook County lawsuit, settled earlier this year for undisclosed terms, filed by a woman who accused a now-deceased Claretian priest, the Rev. Thomas Paramo, of sexually assaulting her as a young woman at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church. According to her lawsuit, the assault happened on the day of her wedding rehearsal in 1986 when he was taking her confession.

The Claretians “ignored” his “predatory and pedophiliac tendencies,” according to the lawsuit, which says the order “engaged in a pattern and practice of purposefully hiding claims of sexually abusive behavior to protect their reputation and avoid the scandal that would result if parishioners and the public at large were aware of the incidents.”

Paramo died in 2004 at 77. His funeral was held at Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Unlike dioceses — the geographic units of the Catholic church overseen by a bishop appointed by the pope — Catholic religious orders largely run independently, with their own hierarchies, typically operating across diocesan boundaries.

Within the Cook and Lake county boundaries of the Archdiocese of Chicago, they need Cupich’s approval for any members to engage in public ministry.

But nothing requires them to heed his call for them to post a public listing of predatory clerics and their past assignments — measures some Catholic church leaders and victims advocates see as a way to publicly recognize the scope of child sexual abuse by clerics and also help victims with healing.

And not all have, as the Chicago Sun-Times has reported.

But, unlike the Claretians, many of them still describe on their websites how they’ve dealt with clerical sexual abuse. And some provide information on filing complaints against their members. Among them:

- The Dominican order, which runs Fenwick High School in Oak Park. Several years ago, the leader of the Dominicans’ Province of St. Albert the Great, the Rev. James Marchionda, said the order was preparing to make public a list of its members deemed to have been credibly accused of sexual abuse. That hasn’t happened. And Marchionda recently said he doesn’t know whether that will be done.

Yet, on the Dominicans’ website, under a heading titled “Protecting Children,” the order spells out standards for how members should conduct themselves and provides contact information for anyone wanting to file an abuse complaint or speak with a “victim assistance coordinator.”

The Dominican province based in Chicago that covers much of the Midwest says it “has a comprehensive plan to make sure that we minister responsibly and maintain an environment in our ministries that is safe for children and other vulnerable people. Our program is accredited through Praesidium” — a Texas company specializing in abuse prevention — “which assures us that we have achieved the highest standard in child abuse prevention.”

- The Passionists order, whose Chicago-area province is based in Park Ridge. Like the Dominicans, it has not publicly posted a list of its predator priests.

For decades, the order ran Immaculate Conception Church in Norwood Park on the Far Northwest Side, where the Rev. John Baptist Ormechea was assigned from the late 1970s to the late 1980s. In the early 2000s, several men accused Ormechea of having sexually abused them when they were growing up and attending Immaculate Conception. Order officials deemed the accusations credible, though, by then, the statute of limitations for Ormechea to face criminal charges had expired, the Sun-Times has reported.

Also like the Dominicans, the Passionists order has a section on its website addressing the sexual abuse crisis. Titled “Safe Environments,” it quotes the Rev. Joseph Moons, head of the Passionists’ Park Ridge province, as saying: “We affirm our commitment to the protection of young people, to creating safe environments where young people flourish as children of God and people of faith.

“We pledge to continue to implement child safety education, background checks, reporting and external reviews of our child protection efforts.”

- The Marist Brothers order, which runs Marist High School on the Far Southwest Side. It similarly posts no list of abusers but offers information online about its efforts to curb, investigate and atone for sexual abuse.

The Augustinians order, which operates Providence Catholic High School in New Lenox and St. Rita High School on the South Side. The order — which has faced two lawsuits in Cook County accusing its clerics of abusing students at the schools years ago — has not made public a list of its predator priests. But it, too, has information on its website dealing with “survivor assistance.”

Though representatives of the Claretians did not respond to interview requests about their handling of clerical sexual abuse, the order is listed as “accredited” on the website of Praesidium, the company that works with organizations on abuse prevention.

A company spokeswoman declined to discuss the Claretians.

According to a statement the company has posted online: “Praesidium accreditation publicly demonstrates an organization’s commitment to safety and adherence to the highest standards in abuse prevention . . . Pursuing Praesidium accreditation gives an organization access to best practices, written resources to strengthen prevention efforts and consultation with our experts.”

The Claretians began staffing Our Lady of Guadalupe in 1924.

It also established and oversees the National Shrine of St. Jude that’s part of the parish and has two bone relics associated with Jesus’ apostle Jude, the patron saint of impossible causes, according to the group.

Nationally, the order runs or helps staff fewer than a dozen parishes.

For years, those included Holy Cross / Immaculate Heart of Mary Church in Back of the Yards, which the order left within the past few years. Serving the mostly Latino parish for a time was the Rev. Bruce Wellems, a Claretian who acknowledged that, as a teenager, he molested a young boy. Wellems has since left the priesthood.

The order was sued by Wellems’ victim in 2016 in a case that was settled without a provision the plaintiff had pushed for — that the order would disclose records on abuse.

The Claretians order also runs a publishing division in Chicago that publishes the magazine U.S. Catholic.

A Claretian priest named Ronald Luka, who occasionally wrote for the publication, was sued in 2002 in Miami-Dade County by former altar boys who accused him of molesting them in the 1970s at his Florida home and on excursions that included a road trip to Chicago, according to published accounts.

Between 1984 and 1999, Luka listed his address as his order’s Oak Park home. In the early 1980s, he was a “resident priest” at Our Lady of Ransom Parish in Niles.

The first accusations against Luka that were found to be credible were made in 1999, while he was living in Oak Park, though they involved allegations of sexual misconduct more than 20 years earlier in New York, the order’s Chicago attorney, Richard Leamy, said in 2002.

The Diocese of Rockville Centre, which covers Long Island, New York, has Luka on its list of “accused clergy.” It says the accusations involved incidents at a State University of New York campus, a rectory in Nassau County and a Boy Scout camp in upstate New York, among other places.

The Archdiocese of Miami says Luka “was credibly accused” in 2002, and “the allegations were reported to the Broward [County] state’s attorney’s office.”

Luka died about a decade ago, according to a relative.

In 2003, a man filed a lawsuit in Cook County against the order and one of its other priests, the Rev. Eusebio Pantoja, saying he molested a boy at the cleric’s home and at Our Lady of Guadalupe in the 1970s. A separate lawsuit, filed in 2005, accused Paramo of molesting a girl at Our Lady of Guadalupe in the mid-1960s. Both cases have long since been settled.

A lawsuit filed in 2014 accused three other priests at Our Lady of Guadalupe of molesting a boy at the Southeast Side parish at different times between 1965 and 1972, when the boy was between about 5 and 12 years old and “went to catechism school and attended mass” there.

“The abuse includes but is not limited to occasions when the priests in question would touch and fondle plaintiff’s penis, chest and nipples with their hands and mouths, force plaintiff to massage the priest’s penis and bend plaintiff over a desk to sodomize him,” the suit said.

A judge dismissed the case, saying too much time had passed before the suit was filed.

Another Claretian priest, the Rev. Daniel Drinan, served at Our Lady of Guadalupe in the 1990s and was assigned to the order’s Chicago-area headquarters, records show. In 2002, while serving parishes near Austin, Texas, Drinan was removed from ministry after being accused of inappropriately touching a child.

In 2012, he was arrested for masturbating on a Southwest Airlines flight from Baltimore to Denver. A 29-year-old woman “observed Drinan looking at pornography on his laptop computer and getting up and down from his seat and getting bottles from his bag,” an FBI agent said in an affidavit. “One of these bottles was lubricant. She saw him reach into his pants and start touching himself.”

A flight attendant saw “his hand wrapped around his penis and was totally exposed,” the FBI affidavit says.

Drinan admitted accessing “an erotic site” using the plane’s Wi-Fi, becoming “aroused” and touching “himself because the lights were out on the aircraft, no one was seated next to him, and he was tired and wanted a release,” the FBI agent wrote.

Drinan pleaded guilty to indecent exposure on a commercial aircraft and was sentenced to two years of probation.

He was laicized in 2014, according to the Diocese of Austin.

Now in his 70s and living in California, Drinan declined to comment.

Lovell was convicted in California of lewd or lascivious acts with a child under 14 and sentenced in 1986 to three years of probation, which he served in the Chicago area while handling “office duties” for his order, according to church and court records.

Another criminal prosecution against him in California was dismissed when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled “that an expired statute of limitations could not be revived.”

In Arizona, Lovell was convicted of molesting minors while serving as a priest there in 1978 and 1979 and was imprisoned from 2004 until last month.

“The acts include rubbing the victim’s penis to the point where the victim ejaculated, touching the victim’s penis and attempting to touch the victim’s anus,” Deputy Maricopa County, Arizona, Attorney Rachel Mitchell wrote in a court filing.

Last year, a man who’d accused Lovell in a lawsuit of molesting him as a boy in the 1980s in California settled the case against him, the Claretians and the Archdiocese of Los Angeles for $1.9 million, records show.

It was “the first case to be settled with a Catholic diocese in California since the passage” of a law creating “a three-year widow in the state’s statute of limitations allowing victims of past childhood sexual abuse to seek justice,” according to Manly, Stewart & Finaldi, the law firm in Irvine, California, that represented the man.

Lovell was laicized in 1992. The following year, he met a woman in New Mexico, a mother of three, he later married.

A sex offender registry shows Lovell, 73, now lives in Phoenix, Arizona. He couldn’t be reached.

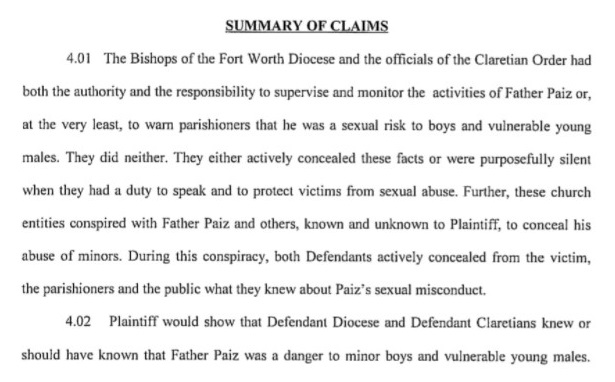

The Rev. William Paiz, another Claretian priest, was accused more than a decade ago of molesting a boy in Texas years earlier and was believed to have been moved by his order to the Chicago area after the allegations surfaced, according to a lawsuit against church officials that was settled in 2012.

None of the other Claretians in this story who are still alive could be reached. None is known to still be involved in public ministry.

Despite the lawsuits and criminal cases and convictions and Chicago connections, just one of the Claretian clergy members accused in court of abuse — Pantoja — is included by the Archdiocese of Chicago on its list of clerics with “substantiated misconduct with minors.”

With only two exceptions, the archdiocese has declined to include anyone from religious orders on its list of abusers, though many dioceses do list abusive order priests who lived or committed offenses on their turf. Among these are the Joliet and Rockford dioceses, whose territories include DuPage, Will, Kane and McHenry counties.

Other church officials have told the Sun-Times that Cupich has been collecting information from them about sexually abusive order clerics who have lived or work in Cook and Lake counties. The cardinal has encouraged the orders to post their own lists.

Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul has been conducting a review that began under his predecessor Lisa Madigan of all six Illinois dioceses regarding diocesan priests — those who answer to Cupich or other bishops — accused of sexual abuse.

Raoul says he has expanded the scope of that review, asking the bishops for any information they have on abusive members of religious orders as well.

He says he’s gotten a commitment from Cupich’s office that it will start including abusive religious order members on the archdiocese’s list of credibly accused clerics.

“We think it’s important for founded cases that they be disclosed on their website,” Raoul says.

If order clergy are “going to be working, presiding or engaging in any way within the diocese, to us, they’re no different from any priest that’s offending,” he says.

Asked whether religious orders also should be posting lists of their members with substantiated child sex claims, Raoul says: “That’d be ideal. Just morally. And I think it’s useful disclosure.”