OPELOUSAS (LA)

Acadiana Advocate [Lafayette LA]

June 18, 2021

By Ben Myers

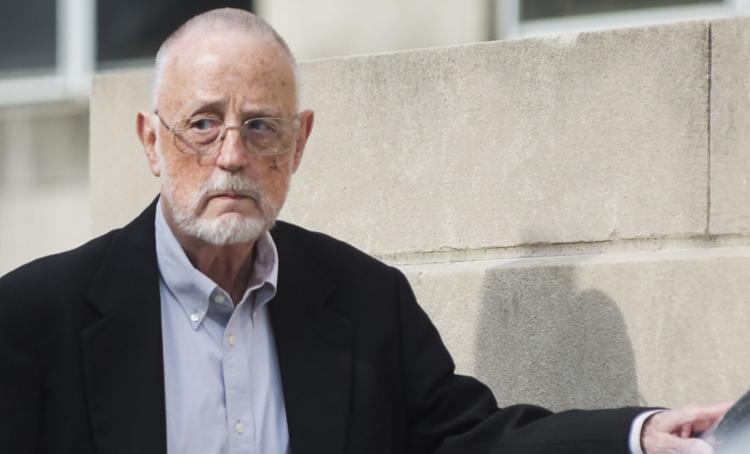

[Photo above: Oliver Peyton hugs his father Scott following a sentencing hearing for former priest Michael Guidry Tuesday, April 30, 2019, at the St. Landry Parish Courthouse in Opelousas, La. Advocate staff photo by Leslie Westbrook]

Disgraced priest Michael Guidry has twice changed his story about the night in 2015 that he molested a teenage altar boy in the rectory of St. Peter’s Church in Morrow, a small community in St. Landry Parish.

When the boy reported the abuse three years later, Guidry initially told St. Landry Parish Sheriff’s Office detectives that he could not recall the fondling. But moments before taking a lie detector test, he admitted rubbing the boy’s genitals.

The molestation continued until the boy stood up to stop it, Guidry wrote in a statement to law enforcement. It had started after they shared “a few drinks,” he wrote, adding that he had recently “replenished” his supply of the boy’s favorite liquor.

Guidry, 78, pleaded guilty to child molestation and is now serving a seven-year prison sentence at Dixon Correctional Institute. Though Guidry confessed his crime, he again revised his story in a January prison deposition in the victim’s lawsuit against Guidry and the Diocese of Lafayette.

The case was recently settled for an undisclosed sum, and the unsealed deposition provides a rare public glimpse of a predatory priest’s after-the-fact justifications. Facing potential financial liability for himself and the church, but no further legal consequences, Guidry stuck to a consistent theme: The boy, Oliver Peyton, was primarily responsible for his own abuse.

Though Guidry said a head injury had affected his memory, he vividly recalled details that contradicted his earlier confession. In this telling, Oliver drank from his own bottle, one he brought during a previous visit. Oliver guided Guidry’s hand during a nude massage, and it was Guidry who ended things, not Oliver. He did so the second his hand touched Oliver’s genitals.

Oliver has consistently maintained that he passed out after Guidry pushed him to drink pure gin, and that he woke up to Guidry molesting him.

Oliver, now 22, identified himself in the 2018 lawsuit, and witnesses at Guidry’s public sentencing hearing referred to Oliver by name. As a result, his name circulated in local media, including The Advocate. Oliver separately gave permission for his name to appear in this story, but he did not want to be interviewed.

Church officials also changed their stance after a lawsuit put the diocese’s assets in peril. Prior to the lawsuit, the vicar general, Monsignor Curtis Mallet, profusely apologized to Oliver and his family on behalf of the church.

But Mallet later approved legal filings blaming Oliver’s parents for allowing him to be alone with Guidry.

The diocese also accused Oliver’s father, Scott Peyton, who is an ordained deacon, of manipulating the public with “calculated and activist” Facebook posts. What’s more, the diocese attested, Peyton leveraged his relationships with St. Landry Parish judges to tamper with the case.

Three judges recused themselves, citing unspecified conversations with Peyton, who worked as a parole officer at the time. But one judge said he had an equally disqualifying conversation with an agent of the diocese. Another said his familial relationship with a former diocesan official would have necessitated recusal anyway.

The presiding judge, Alonzo Harris, found no basis for the church’s claims against Peyton.

The diocese pursued its legal strategy after Bishop Douglas Deshotel identified the Peytons as Guidry’s accusers, which led some in the tiny Morrow community to ostracize them. In an interview, Peyton said the family never intended to put themselves in the public eye.

“To clear up the speculation, to clear up the lies and defend Oliver’s name, and our family’s name, we had to become more proactive in dealing with it,” Peyton said. “We relied on the church for guidance and direction. But when the hurt comes from the church, you have nowhere to go.”

As part of the settlement, the church issued a three-sentence apology acknowledging the victim’s credibility and denouncing Guidry’s actions.

The apology noted that Guidry is permanently removed from the ministry, but it did not address his employment status. Guidry said in his deposition that he is retired, and that he continues to receive a pension and health insurance through the diocese.

A spokeswoman for the diocese did not respond to multiple requests for interviews and written questions.

Guidry’s lawyer, Steven Dupuis, did not return calls.

‘Dying of curiosity’

The closest Guidry came to accepting fault in his recent deposition was to say he allowed things to go too far, but he repeatedly portrayed Oliver as the aggressor. Guidry said he advised Oliver afterward that Oliver had sinned by “moving in” on him.

“You don’t treat people this way,” Guidry recalled telling the boy.

Guidry insisted he was not motivated by lust, and he had not felt sexual desire in more than a decade. He merely wanted to see what was troubling the boy, and going along with the nude massage at the boy’s behest was the only way.

When plaintiff’s lawyer Kristi Schubert asked if Guidry had thought being alone with a naked teenager was inappropriate, he replied: “it never crossed my mind.

“I was trying to see why he was doing what he was doing,” Guidry said. “I was dying of curiosity.”

Satisfying that curiosity was Guidry’s pastoral duty, he said under questioning. Schubert asked why Guidry did not try to simply talk with the boy, and Guidry again replied that he did not think of it.

“It was better to see what he’s doing,” Guidry said. “And not be lied to.”

Guidry also claimed that supplying alcohol to teenagers to model healthy drinking habits was another of his priestly duties. He noted that he had done the same for the victim’s older brother years earlier.

“They’d only drink one when they would come with me,” he said.

The only exception to the one-drink rule was the night Guidry molested Oliver, when they each had exactly two drinks, he said. He insisted that neither he nor Oliver was intoxicated.

Schubert said in an interview that she has never seen anything like Guidry’s deposition answers in representing more than 50 clergy abuse victims.

“I’ve never heard a person excuse touching the genitals of a 16-year-old boy by saying it was out of pastoral concern for the boy, and they were in no way aroused or interested in it,” Schubert said. “I don’t expect to hear that one ever again.”

‘I don’t want to be told about it’

Guidry said that prior to the victim coming forward he divulged his crime to fellow priests who met regularly in a small, informal support group. If so, it is not clear if state law required the priests to report him to law enforcement — something they did not do.

Clergy are “mandatory reporters,” a category that includes educators, medical personnel and others who must immediately report suspected child abuse. But there is a limited exception for clergy, who are not obligated to report confidential information they receive in the course of their official duties.

“Confidential communication” is defined as anything not intended for further disclosure, leaving room for interpretation, said Cherrilynne Thomas, a child welfare lawyer and former co-chair of the Louisiana State Bar Association’s Child Law Committee.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean just in the context of a confession process,” Thomas said, referring to the Catholic rite.

Guidry identified Revs. Harold Trahan and Buddy Breaux as members of the group of six or seven priests. Trahan and Breaux confirmed being part of the group, but they emphatically denied that Guidry disclosed the abuse to them.

Trahan, who declined comment when reached by telephone, spoke through his attorney. Breaux said in an interview that Guidry’s claims troubled him and the other priests.

“It’s very disturbing to us, because it’s inaccurate,” Breaux said. “If I was put in a position where I was the person who had to speak up with knowledge of some misbehavior, I would have done so. But that wasn’t the case.”

Breaux said he is not angry with Guidry, who was Breaux’s vocational director in seminary and the first priest he served under as a deacon.

Breaux said he visited Guidry in prison about a year and a half ago. They did not discuss the crime that put him there. Breaux is concerned about all child abuse, he said, but Guidry’s confession does not tarnish his view of his old friend and mentor.

“I’m not even aware of what he confessed to, and I didn’t look into it. I don’t know about it, and I don’t need to know about it. I don’t want to be told about it. I just want to be a friend to him,” Breaux said.

Hostile scrutiny

Guidry’s close relationship with the Peyton family was no secret.

They regularly shared meals and celebrated holidays and birthdays together. Scott Peyton served under Guidry as a deacon. Guidry paid Oliver to do yard work and bought him things on Amazon. He had fostered a similarly close relationship with Oliver’s brother years earlier. He let the boys drink and smoke when their parents weren’t around.

“In hindsight, we can go back and see that all of us were groomed. Oliver, our family, it was a continuous grooming process,” Peyton said.

Guidry’s first visit with law enforcement, in which he did not admit to a crime, came one week before Oliver’s brother’s wedding in spring 2018. Rumors that the Peyton family was involved swirled almost immediately, Peyton recalled.

On the wedding day itself, guests grew distracted by their phones. A group of friends ignored Peyton and his wife, Letitia Peyton, as they walked to the reception. Some guests left.

Peyton said he quickly learned the reason: Deshotel had just notified clergy of Guidry’s administrative leave, pending an investigation of child molestation allegations. The email did not identify the victim, but Deshotel erased any doubt as to the accuser’s family when taking questions from reporters two days later.

Deshotel mentioned the family had left St. Peter’s for a church in Ville Platte. That description applied only to one family. Suspicions surrounding the Peytons exploded into hostile scrutiny.

“We have six children. They knew it was our family, and they began to speculate on which one of our children it was,” Peyton said.

Guidry’s confession had fallen on deaf ears. A Guidry supporter approached a Peyton family member at Wal-Mart to tell her the allegations could not be true, he said. So too did a eucharistic minister serving communion to Peyton’s 90-year-old grandmother.

“We felt extremely betrayed by at least half or more of the community, churchgoers, parishioners, for believing Guidry didn’t do this,” Peyton said.

The family now attends a small Latin Mass in Plaisance, but Peyton has stepped away from his role as a deacon. He and Letitia have tried to instill a new type of faith in their children.

“Everything we have taught them about being faithful Catholics, being faithful Christians, we have had to kind of redirect,” Peyton said. “My faith in Christ is there, but my faith in the institution is almost decimated.”

Apologize, then blame

Deshotel never apologized for outing the family, but his second-in-command did. Vicar General Curtis Mallet told Peyton in a text that he “cringed” at Deshotel’s comment to reporters.

“I don’t know what he was thinking but he made a mistake,” Mallet wrote. “I’m so sorry.”

Mallet apologized again later that summer, after parishioners held a goodbye luncheon for Guidry, who was awaiting sentencing. Mallet called the luncheon “a terrible disrespect and insensitivity” in a letter to Oliver.

Mallet apologized “in the name of the Church,” and said he felt “shame that you were harmed most intimately by a person who should have modeled for you the exact opposite.”

But the contrition was short-lived. Four months later, the diocese answered the Peytons’ lawsuit by claiming “the fault of the plaintiffs” offset damages owed to them. In another filing, signed by Mallet, the diocese claimed the Peytons “willingly and knowingly violated the rules of the safe environment policy by sending their teenager alone to the rectory.”

The church adopted its Safe Environment Policy after the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops adopted guidelines for addressing child sex abuse two decades ago. It bans clergy from sharing overnight accommodations with youth. It also instructs clergy to “be aware” of the appearance of impropriety of being alone with youth.

It is not clear how parents allowing their children to be alone with a priest would constitute a violation on their part.

“The church always says ‘We are behind you, we support you, thank you for bringing this important information to light,’” said Schubert, the plaintiff’s lawyer. “The things the church says publicly don’t always fit with their litigation style.”