SPRINGFIELD (MA)

WAMC, Northeast Public Radio [Albany NY]

May 25, 2021

By Paul Tuthill

One day after a prosecutor in western Massachusetts publicly accused a recently deceased former priest of murdering an altar boy a half-century ago, there was a call for the Springfield Diocese to release its files.

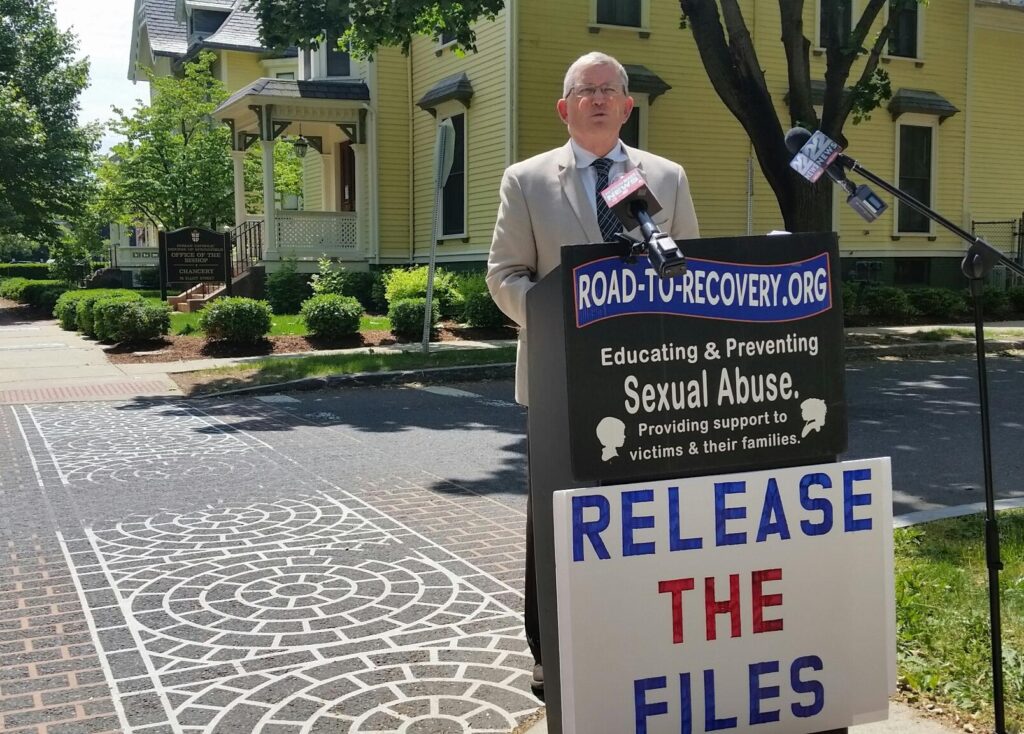

Standing across the street from the headquarters of the Springfield Diocese, Robert Hoatson called for Bishop William Byrne to open the archives that might show what Catholic church officials knew about the sexual abuse and 1972 murder of 13-year-old Danny Croteau by then-priest Richard Lavigne.

“And tell us the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth about what was known for 49 years about father Richard Lavigne and other priests and clergy in the Diocese of Springfield,” Hoatson said.

A former priest, Hoatson is co-founder and president of Road to Recovery, Inc., a New Jersey-based non-profit that assists victims of clergy sex abuse and their families. He said he was a “pastoral supporter” of Croteau’s parents, who are both dead.

Lavigne was a serial sexual abuser for at least three decades. In the early ‘90s he pleaded guilty to two counts of indecent assault and battery and was sentenced to 10 years on probation. He was removed from active ministry, but the diocese did not attempt to change his status as a member of the clergy. He was not defrocked by the Vatican until 2003.

During Lavigne’s time as a priest in the Springfield Diocese, he would have been supervised by two bishops, Christopher Weldon and Thomas Dupre, who have both been credibly accused of sexual abuse.

“The chief administrators of this diocese, who are known as bishops, have themselves had checkered pasts,” Hoatson said.

He acknowledged it is unlikely the Springfield Diocese will ever make its files on Lavigne public.

“The church will never voluntarily turn over anything, unless they are forced to,” Hoatson said.

Joining the press conference by phone was Mitchell Garabedian, the Boston attorney who has represented scores of clergy sex abuse victims. He called on Pope Francis and Cardinal Sean O’Malley of the Boston Archdiocese to order Byrne to release the files.

In a statement, the Diocese said it handed over what are sometimes referred to as “secret files” to a grand jury convened in 2004 to investigate the Croteau case. Also, investigators executed a search warrant on the offices and rooms of then-Bishop Dupre and other diocesan offices.

Lavigne had been the only person every publicaly identified as a suspect in Croteau’s murder. On Monday, Hampden District Attorney Anthony Gulluni announced he had authorized state police to seek a criminal complaint just hours before Lavigne died last Friday.

“We were prepared to then prosecute Richard Lavigne and prove his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt,” Gulluni said.

New evidence against Lavigne included statements he made during hours of recent interviews with a State Police detective. He does not confess to the murder, but admits he was the last person to see Croteau alive along the banks of the Chicopee River.

At one point in the recorded interview, the 80-year-old Lavigne said he told no one about seeing Croteau’s body floating face down in the river because people would speculate he was to blame.

“If I shared this with the public, they really wouldn’t believe it,” Lavigne said in the recording played by Gulluni at Monday’s press conference.

“When I say they wouldn’t believe it, they would probably build conjecture around the revelation that I make,” Lavigne tells the State Trooper. “I’d sooner forget the whole thing, frankly.”

Another piece of evidence was a letter with apparent references to the case that a forensic linguist recently concluded was written by Lavigne.

Gulluni said an employee of the Springfield Diocese knew about the letter. It was seized by State Police from Lavigne’s home in 2004.