NEW YORK (NY)

Forward [New York NY]

April 27, 2021

By Hannah Dreyfus

A senior leader of the Reform movement whose rabbinic privileges were briefly suspended two decades ago for “personal relationships” that violated ethical codes in fact sexually harassed or assaulted at least three women, including one who was a minor when the misconduct began, an independent investigation by Manhattan’s Central Synagogue has found.

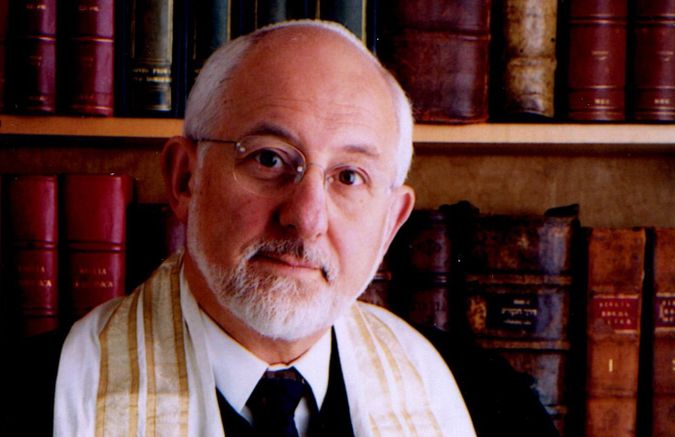

Rabbi Sheldon Zimmerman, who was senior rabbi at Central from 1972 to 1985, resigned his position as president of Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in 2000 after the Reform movement’s Central Conference of American Rabbis ruled that his relationships had broken its rules. But neither CCAR or HUC provided details of the misconduct at the time, leaving the impression that Zimmerman had simply had consensual affairs, and he went on to serve as vice president of the Birthright Israel program and rabbi of the Jewish Center of the Hamptons.

Now, lawyers hired by Central have found credible evidence that Zimmerman engaged in “sexually predatory” behavior and used the philosopher Martin Buber’s I/Thou theology, which describes the relationship between man and the divine, as a way to justify his sexual behavior, according to a letter sent to congregants Tuesday afternoon.

“We are devastated that a member of our clergy could abuse our (or any) pulpit and position of power within our community the way that Rabbi Zimmerman did,” said the letter, which is signed by Rabbi Angela Buchdahl, Central’s senior rabbi, as well as its executive director and board president. “This was a gross manipulation of his spiritual authority.”

Nancy Levy, who taught at Central Synagogue’s youth program in 1974, told the Forward in an interview that she was manipulated into a sexual relationship with Zimmerman, who was her boss.

“How could he have done this as a rabbi? How could he have trapped us with the ‘I/Thou?’” Levy, now 74, said in an emotional phone interview. “He so misused Buber’s words,” she added. “He told me he was looking to get to God through me.

“It’s just like the Catholic priests — he used religion to justify his predation and tore down Judaism and a part of me in the process.”

The lead investigator hired by Central Synagogue confirmed that a second victim was 15 years old and a member of Central Synagogue’s youth group when Zimmerman first struck up a relationship with her in 1970. According to the investigator, the woman was 17 when Zimmerman first began to fondle and kiss her.

Central’s letter to congregants said that it would continue to investigate any new allegations of women who come forward, review its policies and procedures around sexual misconduct, and, in the next two months ”make necessary adjustment” to ensure that Rabbi Zimmerman’s tenure in the community not be “lauded” in its building, archives or website.

“We have to challenge ourselves as a congregation to speak the truth and to never let any of us be bystanders,” the letter said. “May we walk forward with humility, repentance, and a determination to never allow the leadership positions of our community to be perverted or misused.”

Rabbi Zimmerman now lives outside Dallas, where he was senior rabbi of Temple Emanuel from 1985 to 1996, and where he is listed on the website as teaching a Kabbalah course. He did not respond to requests for comment.

The revelations about Rabbi Zimmerman have prompted a review of policies around sexual misconduct not only at Central but also at HUC and CCAR. They come amid a broader reckoning over sexual harassment and assault at HUC and the world of Jewish Studies after some scholars attempted earlier this year to help the sociologist Steven M. Cohen, who was shunned by the Jewish world after five women accused him of misconduct in 2018, re-enter academic discussion circles.

CCAR, the Reform movement’s rabbinical organization and the body that originally sanctioned Zimmerman in 2000, said in a statement on Tuesday that it had moved five months ago to conduct “an audit and assessment of our ethics system” and promised that review would “result in meaningful change.” The statement called the revelations about Zimmerman “devastating” and said it sparked “institutional self-reflection” over the group’s original investigation of his behavior.

“When a rabbi misuses the power and trust of their title, we are all harmed,” said the statement, signed by the organization’s president and chief executive. “We know that we are at an inflection point. We know, too, that our commitment to real change means that there is difficult but necessary work ahead. The road in front of us will not be easy, but the safety and well-being of the communities our rabbis serve is a priority.

An HUC spokesperson said the rabbinical college had decided this month to engage an independent law firm to conduct a review and analysis of allegations relating to sexual misconduct and gender bias. This follows the creation in January 2020 of a presidential task force to address instances of harassment and bias.

Andrew Rehfeld, president of HUC, wrote in an April 23 email to faculty, staff, students, alumni and board members that the new investigation would be “thorough,” “impartial” and “undertaken with thoughtfulness and urgency,” promising more specific details “in the weeks ahead.”

“Our board and administration is really distressed by the accounts coming forward,” Jeanie Rosensaft, the HUC spokesperson, said in an interview. “We’re committed to ensuring the wellbeing, dignity and respect of every individual in our community,” she added. We are seeking to hear people’s truths and we are seeking teshuva with thoughtfulness and urgency.”

Levy, telling her story publicly for the first time, said in the interview that the inappropriate relationship with Rabbi Zimmerman began in 1974 and took a turn one day in the fall of 1975 when he called her and said he was coming over to her apartment after dropping his wife off at the airport.

“Then, I knew he was going to ask me to have sex — that he intended to consummate what had been going on,” she recalled. When Zimmerman arrived, Levy said, the two of them got undressed but did not have sex because Zimmerman was unable to have an erection.

“He told me then that I was the only person he’d ever done this with before aside from a nun,” she recalled. “In my mind, I was like, this is really weird.”

Levy said Zimmerman continued to try and reach out to her after the incident in her apartment, but she declined his overtures, quit her teaching position at the synagogue and parted ways with Reform Judaism, working instead as an educator at a church in Manhattan.

“I would be seriously surprised if I could ever affiliate with the institution of Judaism again after what happened,” she said. “I can go there for my mother’s yahrtzeit and for all the members of my family whose names are on those plaques,” she said, referring to Central Synagogue. “But after being made to feel so unsafe in that place, my relationship with that synagogue and my Judaism is permanently damaged.”

Levy spurred Central’s investigation last fall when she decided to come forward with her never-before-heard allegations against Zimmerman after happening upon a Rosh Hashanah Zoom service led by Buchdahl. “In her drasha, Rabbi Buchdahl spoke about confronting racism in our community,” Levy recalled. “Even though I hadn’t thought about Shelly for years — decades — it all came rushing to the surface. I realized it was my turn to confront the injustice that I had experienced, as our nation confronts its own legacy of slavery and racism.”

Rabbi Rick Jacobs, president of the Union for Reform Judaism said he was “profoundly saddened to learn of the painful violations endured” by members of the movement.

“Sexual misconduct has no place in our houses of worship, where our holiest ethical teachings should be lived by all especially by our clergy who care for us at the most vulnerable moments in our lives,” Jacobs said in an emailed statement.

“Our Jewish tradition is unyielding in holding all of us responsible to create safe environments where the culture of respect prevails and where there is openness to hear – and address – the failings of our leaders,” he added. “We will not rest until every space within the Reform Movement is safe and those culpable are held accountable.”

Rabbi Buchdahl said in an interview that she felt “morally compelled” to investigate after Levy came forward, followed by two other women who shared their experiences and what she described as “the lasting harm.”

“Their stories were devastating and our investigation deemed their accounts to be credible,” she noted. “We asked these women directly what could bring any measure of closure or healing, and they shared how important it would be for us to make the past public so there is no sense that a transgression this serious can be swept under the rug by the wider Jewish community.”

Part of that reckoning will include “amending” Rabbi Zimmerman’s legacy at Central “to reflect the entire truth of his rabbinate,” said Rabbi Buchdahl.

“As painful as the reckoning may be, it is necessary for any religious institution to face its history in full. As our tradition teaches, we cannot shape our future if we ignore our past. For serious sexual misconduct, no one should want to cover up the abuse, no matter how long ago it occurred,” she said.

Correction: The original version of this article quoted the lead investigator hired by Central Synagogue as saying that Rabbi Sheldon Zimmerman started a relationship with one woman in 1971, when she was 16; after publication, the investigator said it had started in 1970, when she was 15. The original also misstated the full name of the Reform rabbinical school where Zimmerman was president. It is Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, not Jewish Institute of Learning.