CHICAGO (IL)

Chicago Sun-Times [Chicago IL]

April 16, 2021

By Robert Herguth

What makes James Griffith stand out amid the scandal over sexually abusive clerics is how many chances the Catholic church hierarchy had to tell the public about him — and how many times it failed to do so.

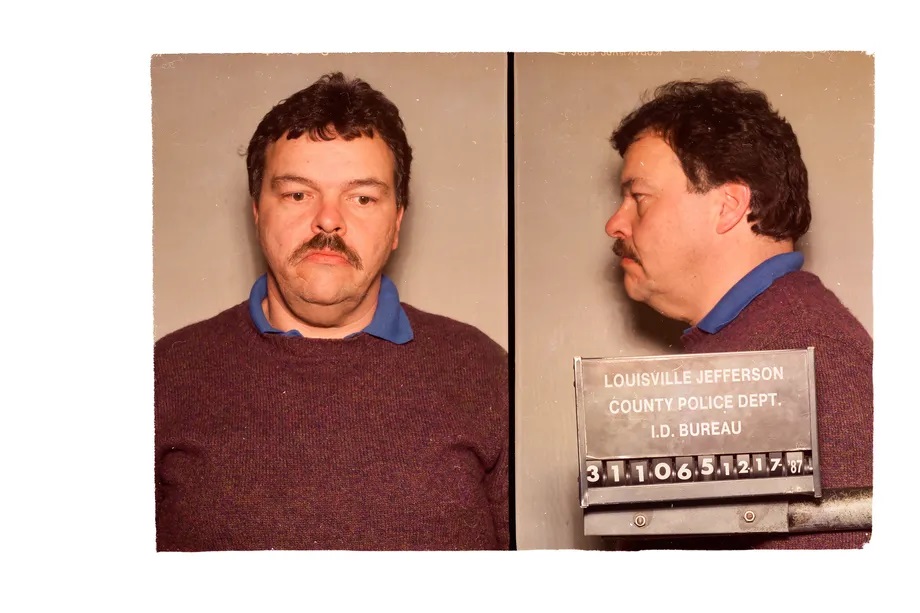

[Photo above: Deacon James Griffith was moved to Chicago and other church jurisdictions after being convicted of a child sex offense in 1988 in Louisville, Kentucky. Louisville Metro Police Department]

More than a decade after pleading guilty in 1988 to sexually abusing a young boy in Louisville, Kentucky, Deacon James Griffith was moved by his religious order to a monastery next to Immaculate Conception School in Norwood Park.

The Passionists — the Catholic religious order that at the time was overseeing the church and school just north of the Kennedy Expressway on the Northwest Side — say he was assigned there in 2002 “to work in the provincial office” on the third floor.

But they didn’t initially tell Immaculate Conception parishioners about his child sex crime conviction or a lawsuit accusing him of molesting another Louisville boy in the 1970s.

Griffith’s past came out in 2003, the year after he was moved next to Immaculate Conception. And when upset parents and other church members packed a meeting with a top priest there, the deacon was soon sent packing.

Amid the latest, ongoing scandal regarding the sexual abuse of minors by clergy, many Catholic dioceses and religious orders now post lists on their websites naming abusive clergy and detailing their past assignments.

But the Passionists do not.

That’s despite Cardinal Blase Cupich having called upon orders that operate within the geographic territory he oversees — Cook and Lake counties — to do so.

Griffith lived at the towering, red-brick monastery at Harlem and Talcott avenues from 2002 to 2003 and also was stationed in Chicago from 1987, the year he was arrested, until 1988, according to his order.

But, despite his criminal conviction and despite having lived and worked in Chicago, Griffith isn’t included on the Archdiocese of Chicago’s own list of abusive clerics. That’s because Cupich doesn’t include order clergy on his list, though other dioceses do so.

His list includes diocesan clergy — those who directly reported to him or his predecessors. It does not include priests and other clerics from the largely autonomous religious orders that operate in the boundaries of the Chicago archdiocese.

It’s not that Cupich doesn’t have that information on the order clergy. As Pope Francis’s representative in Chicago, he has been collecting detailed information on abusive order clerics who have worked in Cook or Lake counties, the Chicago Sun-Times reported in February.

Griffith, 78, now lives in Michigan, within the boundaries of the Archdiocese of Detroit, which posts a list of diocesan and order clerics who’ve lived or worked in that jurisdiction and are deemed to have been credibly accused of sexual abusing minors.

Griffith wasn’t on its list, either — until a Sun-Times reporter asked why that was the case. He subsequently was added earlier this month.

Nor is his name on the list maintained by the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston, where he lived in from 1971 to 1973 and from 1988 to 2000 while helping to run a charity that had young volunteers.

He also won’t be found on the lists published by the Archdiocese of San Antonio, where he lived in 2003 and 2004, or the Diocese of Orlando, where he was based from 2004 to 2007, records show.

Representatives from those church agencies didn’t respond to questions, couldn’t be reached or said they couldn’t explain Griffith’s absence from their lists.

The Passionists said that, though it didn’t inform the public, it did notify the dioceses of Griffith’s presence and his criminal history.

Griffith is hardly the only cleric to have fallen through the Catholic church’s stepped-up efforts to inform the public about predators within its ranks because he is a member of a Catholic religious order. The Sun-Times has reported in recent months on other cases involving orders operating in the Chicago area including the Passionists, the Dominicans, the Society of the Divine Word and the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart.

What makes Griffith’s case stand out from some of the others is how many chances the Catholic church hierarchy had to tell the public about him — and how many times it failed to do so even amid the reforms instituted in the United States amid its latest scandal over predator clerics.

The only other jurisdiction where there appears to be a mention by the Catholic church of Griffith’s past troubles is the Archdiocese of Louisville, which posted a list on its website in 2019 that includes his name among three credibly accused clerics from the Passionists to have served in that area. It doesn’t say, though, what he’d done.

“Deacon Griffith was on the list because of a conviction in 1988 and a lawsuit in 2002,” a spokeswoman for the Louisville archdiocese says. “James Griffith was a deacon in the Passionist order and was named in a May 2002 lawsuit against the Archdiocese of Louisville, in which he was accused of abuse of a minor between 1972-1974.”

That suit was settled under terms that weren’t made public.

The Louisville archdiocese spokeswoman says Griffith “was charged in 1988 for indecent or immoral practices of another victim-survivor. This abuse occurred between 1974 and 1977. He was sentenced to five years’ supervised probation in this incident. Both of these situations involve his service at St. Raphael Parish in Louisville.”

Griffith remains a deacon, a clerical rank with many of the same powers of a Catholic priest, though he’s no longer allowed in public ministry, according to his order.

“James Griffith is currently residing at a residential facility for seniors in Farmington Hills, Michigan,” says the Rev. Joseph Moons, who heads the Passionists province based in Park Ridge that covers the Chicago area. “There are no families permitted to live in the facility, and he does not have any access to minors. He is subject to a restrictive safety plan.”

“As part of his safety plan, he is closely monitored and supervised by several individuals, and his travel is monitored and restricted. One of his supervisors resides with him in the same facility. He is not permitted to present himself as a functioning deacon. He is not permitted to participate as an officiant at Mass or engage in any public ministry. He does not dress in clerical garb.”

Griffith doesn’t appear on any government-run sex-offender registries in Kentucky, Illinois or other areas where he spent time.

Moons says Griffith “was accused of having improperly touched a minor over his clothes while wrestling and swimming” — though court records indicate the misconduct was more severe.

“He was sentenced to five years of supervised probation,” Moons says. “He was not required to register as a sex offender as a result of this guilty plea. This conviction was expunged.”

“All allegations against James Griffith occurred in Louisville,” Moons says. “No allegations have been made against James Griffith in the Chicago area.”

Reached on the phone by the Sun-Times, Griffith says some of the dates of the incidents mentioned by a reporter are incorrect but otherwise says only: “You need to talk to the province. You need to talk to the boss. Beyond that, we’re done.”

Moons says that in 2003 “a public meeting was held at the Immaculate Conception parish hall, where there was a discussion regarding James Griffith . . . residing at the monastery.”

He says Griffith “was subsequently moved out of the monastery,” a 60-room landmark that overlooks Immaculate Conception’s school grounds, once included an outdoor swimming pool and has since been sold by the order and converted into senior housing.

Griffith “was the only person with a known allegation to reside at the monastery,” according to Moons. “No allegations have been made regarding his time while residing at the monastery.”

The parish already was in an uproar in 2003 after child sexual abuse allegations had been made against the Rev. John Baptist Ormechea, who was pastor there between the late 1970s and late 1980s. The priest had left Immaculate Conception in 1988 and been ministering in Louisville for a decade when several men came forward in 2002 and said he molested them as kids during his time as pastor of the Far Northwest Side church, the Sun-Times reported in March.

Those allegations were found by the order’s leaders to be credible, but the statute of limitations on charging Ormechea with any crime had by then expired.

As with Griffith, Ormechea isn’t included on the Chicago archdiocese’s list of sexually abusive clerics.

Though Cupich and his spokeswoman have declined interview requests or to respond to questions for months, the spokeswoman previously said the cardinal decided to publicly name only credibly accused diocesan priests and to leave it to the independently operated Catholic religious orders to handle any public mention of their members.

The meeting that Moons cites took place Jan. 13, 2003, and centered on Ormechea, according to a parish bulletin that said the gathering drew about 150 people. It also included a discussion of Griffith’s presence at the monastery adjacent to Immaculate Conception.

“I would say that the open forum was frank, honest and at times angry,” a priest from Immaculate Conception identified as “Father Mike” wrote in the church newsletter at the time. “Shock, sadness, betrayal and a sense of who can you trust were feelings expressed.”

“Several questions came up,” the priest wrote. “About fifteen years ago two allegations were made against a Passionist priest who had already died. The Passionist congregation ministered to these men and made cash settlement. About the same time in Louisville, Ky., a Passionist deacon was accused of sexual misconduct with a minor. He was prosecuted, admitted his guilt and served the sentence imposed by the court.”

“In the spring of 2002 this man was transferred to our Chicago monastery and resides there,” though “he is not allowed to do any public ministry or have contact with minors.”

“Several school parents strongly said that they did not think this was an appropriate residence for him considering the nearness of the school.”

The parish bulletin from the next week noted that Griffith was moved out of the monastery on Jan. 17, 2003.

Father Mike wrote that he “personally talked to Jim on Tuesday evening following the open meeting. He can understand parents’ concerns. I believe he has accepted this transfer as best as can be expected. Since he arrived in early 2002 he found community members supportive of him as a person. He will miss this.”

In 2013, the Passionists left Immaculate Conception, now staffed by priests who answer to Cupich.

Moons won’t say how many Passionists in the region have been credibly accused of child sex abuse.

Asked about settlements and costs for sex abuse claims against the Passionists, province administrator Keith Zekind says, “That information is not readily available and has not been aggregated. Most of the fees and expenses that were incurred over a decade ago were paid by the province’s insurance carriers.”

Court records show Griffith was charged in Kentucky in 1987 with offenses that included sodomy in the first degree “by engaging in deviate sexual intercourse with . . . a person less than twelve years of age.”

Griffith’s address was listed in court papers as the Catholic Theological Union, a Hyde Park graduate school his order helps run.

According to an account in Louisville’s Courier Journal newspaper, the police secretly recorded a conversation between Griffith and his victim in which the deacon said that, as a child, he had been molested: “When I was a kid, the same thing happened.”

In 1988, records show, Griffith pleaded guilty to first-degree sexual abuse and indecent or immoral practices. The sodomy charge and another sex abuse charge were dropped.

A judge sentenced Griffith to two months in jail and five years of probation and told him that he “shall attend sexual abuse counseling for a minimum of one year” and “hold no position of trust with children,” the records show.

Donald Rigazio Jr., now 57, tells the Sun-Times he was the elementary-schooler at St. Raphael sexually abused by Griffith in the case in which the deacon was charged and pleaded guilty. Records confirm that.

For years afterward, Rigazio says, “I didn’t trust anybody,” and life became “a struggle.”

He says he wanted to kill himself more than once — including one moment of despair when he held a gun to his head but a police officer talked him out of pulling the trigger. He says he abused drugs. Armed robberies sent him to prison for years in Colorado and Idaho.

“For a long time, I didn’t believe in God any more — what kind of God let’s this happen to a child?” Rigazio says of the sexual abuse.

But while locked up, he says, everything changed for him.

“I went to prison, and I got saved” and “accepted Christ in my life,” Rigazio says, and began what he describes as a long journey toward healing.

In 1999, years after Rigazio’s abuse, Griffith was running Steven’s House in Houston, “a community residence of men and women living with HIV/AIDS,” according to a newsletter for the now-defunct organization that’s named for a Passionist priest who died of AIDS after the order says he contracted HIV from a blood transfusion.

The center, which opened in 1994, “accommodate[d] six residents at a time” and provided “persons living with AIDS, who might otherwise be homeless, a secure place to live while aligning the services necessary to move towards independence.”

“Jim was brought to Houston apparently to care for a priest who was dying of AIDS, so he learned a lot about AIDS, and he started Steven’s House,” a former volunteer there, speaking on the condition of not being named, says of the church deacon. “It was a great facility during its run. He had a real knack for working with those folks.”

The ex-volunteer was surprised to learn that Griffith previously had been convicted of a child sex offense but says there were no problems with Griffith’s working at Steven’s House, which had a “handful” of child volunteers.

Why Griffith left Steven’s House wasn’t made clear, according to the former volunteer, who says that, at some point, the Catholic church “wanted him to go to Italy and work at the Vatican. That’s the story I was told. They were unhappy when he refused to go.”

According to the former volunteer, Griffith later worked in central Florida, where he was sent “to take care of two elderly priests.”

In 2002, after a groundbreaking series of stories by the Boston Globe about sex abuse by priests and cover-ups by bishops, the Catholic church adopted a stronger stance on abusive clergy, forbidding any of them facing what were deemed by the church to be credible allegations of child sex abuse from engaging in public ministry or interacting with kids.

That was the year Griffith was moved to Chicago.

Religious orders need permission to minister in any bishop’s diocese. But they don’t answer to those bishops, only to their orders, which have their own leadership and operations that typically extend beyond the boundaries of any single diocese.

Pope Francis has left it to individual dioceses and orders about whether and how to make information about abusive clerics public.

Most dioceses now post public lists, which not only provide the public with a better handle on the alarming scope of sex abuse by clergy over decades, but also are seen as tools to help validate and heal victims. But those lists vary in what information they include.

Though the Archdiocese of Chicago doesn’t include order clergy members in its list — Cupich’s spokeswoman has said the orders are in a better position to do so — the lists posted in Houston, Detroit and Louisville include local diocesan priests as well as abusive clergy from religious orders who served in those jurisdictions.

Many orders also make public their own lists, though those, too, vary in what information they provide. The Viatorians, for instance, who run St. Viator High School in Arlington Heights, list names but not past assignments of abusive clergy members. The Jesuits, who run St. Ignatius College Prep on the Near West Side, include both.

The Divine Word clerics, who operate around the world as missionaries and whose Techny grounds near Northbrook serve as their U.S. headquarters, says they are in the process of creating their first list.

The Passionists say they are “considering releasing a list of names of Passionists who have established allegations of sexual abuse of minors.”

The 2002 lawsuit against the Louisville archdiocese accused Griffith of having, decades earlier, molested a second boy, who’d been part of a St. Raphael Boy Scout troop that the deacon helped lead.

An annual directory put out by the Passionists still listed him as a deacon in 2019 and, in a brief biography, said he “engages his neighbors” and is “involved with community celebrations and events.”

Rigazio and his parents also sued the Louisville archdiocese, but the case was dismissed because too much time had passed.

“I didn’t get any money because the statute of limitations had run its course,” he says. “At this point, God’s grace and mercy is sufficient.”

Around Thanksgiving, Rigazio says, he wrote Griffith “a long letter and told him where I’ve been mentally and physically and what he did affected me and how I did get saved.”

He says he told Griffith in the letter that “I forgave him, and ‘I hope you can get your life together, and you can find grace and mercy as well.’ ”

“I never heard from him.”

Rigazio says it’s important that the church be open about priests and other clerics who have sexually abused children. “There should be a national registry.”

“It’s not ‘old news,’ ” he says. “It’s real. They cover up and try to protect their own. It just baffles me.”