JEFFERSON CITY (MO)

Kansas City Star [Kansas City MO]

April 15, 2021

By Judy L. Thomas and Laura Bauer

Seven former students and one parent traveled from across the country to testify Wednesday before a Missouri Senate committee about abuse inside Missouri’s Christian boarding schools.

After hearing about years of abuse, Sen. Rick Brattin, R-Harrisonville, lashed out at the owners and staff leaders of unlicensed schools accused of abuse.

“These aren’t people of faith that are running these. These are evil monsters, and they’re counterfeits of true Christianity,” Brattin said during the 90-minute hearing. “To hear this sort of abuse, I think of Christ when he spoke of harming these little ones — it is better for them to be thrown in the deepest sea than to harm one.

“And to think that these facilities hide beneath the religious aspect of it. Government is instituted by God to be that justice arm. And we are to protect those kids no matter where they’re at. So we’ve got to do whatever we can do.”

Senators heard multiple accounts of abuse and neglect from former students, including three men who attended Agape Boarding School, which is under investigation by the Attorney General’s office.

The former students testified in support of legislation that would for the first time require state oversight of the unlicensed schools, which are exempt from any regulations. The measure has already passed through the House.

Another two dozen former reform school students submitted written testimony to the Senate Committee on Seniors, Families, Veterans and Military Affairs.

One person testified in opposition to the measure. Lobbyist Woody Cozad, who has represented Heartland Christian Academy and community, told lawmakers that he worries about due process and the “constitutional rights of everybody involved, and that starts with the children.”

Known as The Child Residential Home Notification Act, the proposed legislation — identical bills sponsored by Rep. Keri Ingle, D-Lee’s Summit, and Rep. Rudy Veit, R-Wardsville — would require all faith-based boarding schools to register with the state and mandate federal criminal background checks for all employees and volunteers. The schools also would have to comply with fire, safety and health regulations.

Failure to comply with notification and health and safety inspections, or if a facility is suspected of abuse or neglect, could result in the boarding school being shut down or the removal of children.

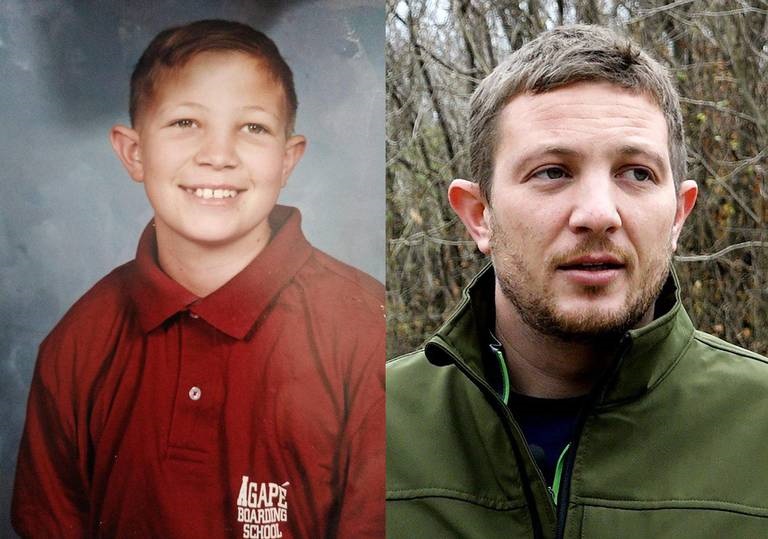

“I am not vindictive,” said Allen Knoll, of the Seattle area, who was sent to a reform school in Mississippi at age 10 and then to Agape in Cedar County in 1999 at 13. “I suffered tremendous abuse, but I’m not here to shut these places down. I’m here to stop people from having to go through the things I had to.

“Nobody was there for me,” said Knoll, now co-founder of a troubled teen advocacy nonprofit. “Nobody was a voice. Not politicians, not my parents, not my family. But somebody needs to be a voice for these kids.

“These are the kids that will hopefully be sitting where you’re at if we take care of them. If we don’t take care of our kids, they’ll be your drug addicts, they’ll be your alcoholics… They’ll be your criminals in your prison systems.”

COURTESY KNOLL/JILL TOYOSHIBA JTOYOSHIBA@KCSTAR.COM

The legislation unanimously passed the House on March 29 and has received key endorsements from the editor of The Pathway, a news publication for the 500,000-member Missouri Baptist Convention, and the Missouri Catholic Conference.

An effort to change the law in 2003 died in the House after intense pressure from opponents, including Cozad, who said it would interfere with religious freedom. But sponsors of the new proposals and child advocates insist the issue is not about religion.

Kelly Schultz, director of the state Office of Child Advocate, said her job is to read child abuse and neglect reports.

“But seeing it done in the name of God and the potential of not only abusing and traumatizing a child, but separating that child from God for eternity, that’s not church versus state,” she said. “This is state versus people hurting children in every setting.”

Under the measures, no government agency would be allowed to regulate or control the content of a school’s religious curriculum or the ministry of a school sponsored by a church or religious organization.

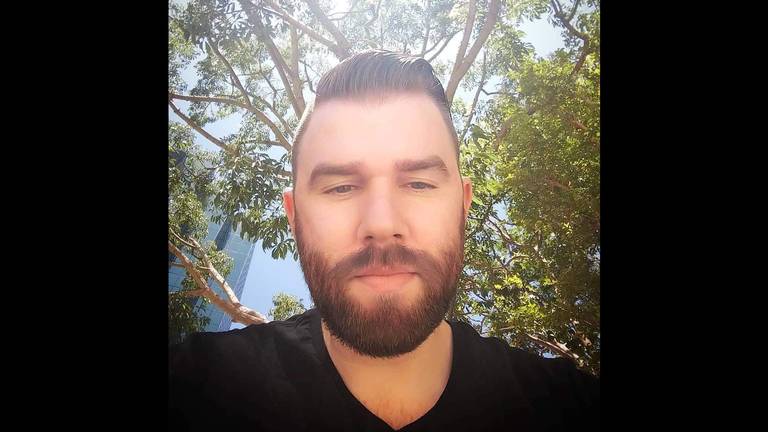

James Griffey, of California, told senators he was a student at Agape from 1998 until he graduated in 2001.

His first night there, he said, he was punched in the face and head-butted after saying the word “gosh” twice when he couldn’t do all the pushups he was ordered to do. It took three other staff members to get the man off him, he said.

“That happened in ‘98,” Griffey said. In recent months, he has worked with a nationwide podcast that interviews survivors of such programs.

“We’ve spoken to a lot of Agape boys,” he said. “And we went to interview a kid that left less than a year ago, and he was expressing these same things that were going on, these restraints for hours at a time, being held down, kids being thrown around, kids being hit.” Other boys that left in recent years told the same stories, he said.

“I thought it stopped. Just know that these people are powerful that are running these schools. They have a lot of money, they have a lot of positions within the community, they are experts at covering up the abuse and silencing people like us that do speak out and discrediting us.”

For months The Star has been investigating faith-based reform schools, which a 1982 law allows to claim an exemption from Missouri’s licensing requirement. The statute also says that DSS cannot require those claiming an exemption to prove that they should be exempt.

Because of the lax law, Missouri has become a safe harbor for unlicensed facilities, some which have been investigated or shut down in other states. They often settle in rural and secluded parts of the state where they can fly under the radar.

Emily van Schenkhof, executive director of The Missouri Children’s Trust Fund, said predators have found a way to exploit the system and to abuse children in the state. That’s why, she said, lawmakers must do something to protect kids from these people.

“They are coming to Missouri and they are hurting our children because of our weak laws in this area,” van Schenkhof told the committee. “For far too long, we have discounted, we have ignored, we have silenced the voices of children. … We have ignored them and we have let them be hurt. And we have an opportunity right now to make a change.”

Dave Bowsher, a former student at Bethel Boys Academy in Mississippi who co-founded the troubled teen advocacy nonprofit organization with Knoll, said many children sent to such facilities “come out way worse” than when they went in.

“Imagine how much damage has been done to child after child after child after child after child over the last 30 to 40 years,” Bowsher said. “I know this is a religious state, and religion is very important to you guys.

“I myself am a Christian. But so many kids that have gone to these facilities say I want nothing to do with God, I want nothing to do with religion, because these people that were supposed to be Christians were abusing me.”

Vickie Dudley, executive director of the Child Advocacy Center in Joplin, said that over the past five years her center has been involved with investigations of unlicensed boarding schools.

“Some of the allegations that we’ve heard are withholding normal food as a punishment and (kids being) forced to eat cold refried beans or bread and water for weeks at a time. We saw a child just last week that had lost 20 pounds in seven weeks, a 12-year-old boy.”

She said children lose their phone privileges and can’t contact parents for weeks or months at a time. All calls are monitored and recorded, children are injured and not properly treated by medical staff and are forced to do hard labor or very difficult exercises for hours at a time as punishment.

“To discipline means to teach,” she said. “One does not need to punish to teach.”

She said authorities are hindered in how they can conduct their investigations because of current law.

“In recent investigations,” Dudley said, “kids were interviewed in a Highway Patrol car in the parking lot of the place where they reside and then returned back to the hands of their abuser.”

And in cases of sexual abuse allegations, authorities couldn’t collect any forensic evidence and kids with injuries were not able to get medical treatment.

“This is unacceptable,” Dudley said. “It’s our role as adults to make sure kids are protected.”

Agape, which relocated to Missouri from Washington in the mid-1990s after coming under scrutiny by authorities in that state, isn’t the only boarding school in Cedar County under investigation.

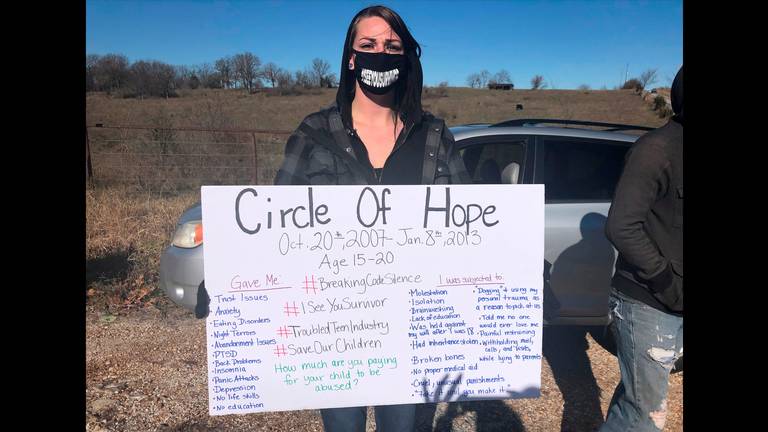

Circle of Hope Girls Ranch, owned by Boyd and Stephanie Householder, closed in September after authorities removed two dozen girls. In March, the Househoders were charged with 102 crimes — all but one are felonies — that include statutory rape, sodomy and physical abuse.

Joseph Askins, of Pennsylvania, told lawmakers he visited Circle of Hope last year when the school was still operating. Askins met Boyd Householder when he attended Agape Boarding School from 2000 to 2004. Householder trained at Agape before opening the girls’ school in 2006.

During the visit to Cedar County last year, Askins said he saw Boyd Householder “pick up a girl and slap her across the face and say, ‘You will call me sir,’ trip her and then throw her down in a pile of horse crap.

“That’s the stuff that goes on behind closed doors. That’s the stuff that still happens at Agape. That can’t happen anymore.

“These places need to stay open for people of last resort, but they need to be run through a strict, regimented routine,” he told senators. “I know animals that get treated better than the students at Agape. If you hit an animal, guess what? You go to jail.”

Sen. Jill Schupp, D-Creve Coeur, thanked those who testified.

“Your stories, your experiences, are horrific,” she said. “But they matter, and you need to know that you’re the ones who are going to make the change…so my heart goes out to you and you’re brave and you’re strong and you’re courageous for being here, and I just want to say thank you for being here.”

Griffey thanked Schupp and other senators for their support.

“This is not about us and what we went through,” he said. “It’s the fact that we know that there’s kids in these programs right now that don’t have a voice and no one’s speaking out for them. That’s why we’re here.”