DUBLIN (IRELAND)

Irish Times [Dublin, Ireland]

April 12, 2021

By Mark O'Brien

Noel Browne leaked letters showing how the Catholic hierarchy put pressure on Cabinet

[Photo above: Gen Richard Mulcahy, minister for education, taoiseach John A Costello, and John Charles McQuaid, Archbishop of Dublin, at the opening of Our Lady’s Hospital for Sick Children Crumlin, in 1956. Photograph: Eddie Kelly]

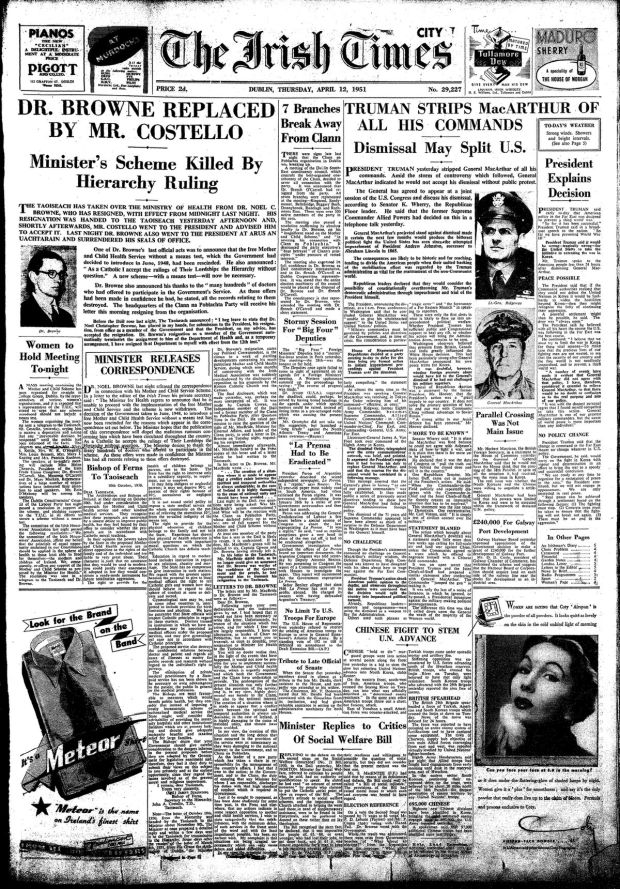

Governmental leaks on healthcare have been much in the news lately but today, April 12th, marks the 70th anniversary of perhaps the most spectacular leak – Noel Browne’s decision to release to The Irish Times correspondence between the cabinet and the Catholic hierarchy on the ill-fated Mother and Child scheme.

The idea of offering education and free healthcare to mothers and infants became a battleground between politicians and bishops that has been interpreted as a demonstration of church power in Ireland and as an episode in which the church overplayed its hand, thus beginning its demise as a political powerhouse.

Originally part of the 1947 Health Act, the idea of a Mother and Child scheme encountered resistance from the Catholic hierarchy. A letter from the bishops to Taoiseach Eamon de Valera indicating that they viewed the scheme as the State intervening in areas that were the domain of the church was enough to freeze the initiative.

As the minister for health in the first inter-party government (1948-51), Noel Browne revived the idea of education and free medical care for mothers and children up to the age of 16 – prompting a cacophony of objections from vested interests.

The Irish Medical Association objected on the basis that the State did not have the resources for such a system. It demanded the inclusion of a means test – which would have the side-effect of protecting the income of doctors who could continue to set their own fees for those excluded them from the scheme.

Browne’s plan was also resisted by the Catholic hierarchy which again objected to the State becoming involved in sex education and to the possibility of non-Catholic doctors treating Catholic mothers-to-be.

The hierarchy’s obsession with controlling all aspect of female healthcare was, by then, well established: its lobbying had resulted in a ban on contraception in 1935 and a ban, in 1944, on a new sanitary product that the bishops viewed as creating the danger of sexual excitement amongst those who used it.

Browne’s attempts to negotiate with the hierarchy went nowhere, with the Bishop of Galway, Michael Browne (no relation), denouncing the Mother and Child scheme as “based on the socialistic principle that children belonged to the State . . . and reminded one of the claims put forward by Hitler and Stalin”.

Having lost the support of his cabinet colleagues, Noel Browne resigned. But, determined to expose just how the State was run, he released the correspondence that had taken place between the hierarchy and the cabinet.

Prior to resigning Browne had met with Irish Times editor RM Smyllie and had secured a promise from him that he would publish the letters. As Browne recalled, he had “been warned that the government might attempt to put an embargo on their publication, but Smyllie, an editor with genuine liberal beliefs, had promised me that should such an embargo be attempted, then, at the risk of going to prison, he would publish and be damned”. True to his promise Smyllie published the correspondence, forcing the other national newspapers to do likewise.

On April 12th, 1951, under the front-page headline Minister Releases Correspondence, The Irish Times reproduced the full text of the letters, the most telling of which, dating from October 1950, was a letter from the hierarchy to taoiseach John A Costello. It described Browne’s scheme as “a ready-made instrument for future totalitarian aggression”, declared that the “right to provide for the health of children belongs to parents, not to the state” and noted that “education in regard to motherhood includes instruction in regard to sex relations, chastity and marriage. The State has no competence to give instruction in such matters”.

It was also alarmed that “doctors trained in institutions in which we have no confidence may be appointed as medical officers under the proposed services and may give gynaecological care not in accordance with Catholic principles”.

The manner in which the government dropped the scheme infuriated Smyllie. In his leading article he denounced the hierarchy’s insistence on a means test (an argument it had taken up having been lobbied by the Irish Medical Association), and noted that the cabinet’s deference to the hierarchy was at odds with its “pathetic appeals to the majority in the Six Counties to recognise that its advantage lies in a united Ireland”.

The whole affair, as Smyllie saw it, demonstrated “that the Roman Catholic Church would seem to be the effective Government of this country”. Undaunted but clearly annoyed, taoiseach John A Costello declared in the Dáil that he was “not in the least bit afraid of the Irish Times or any other newspaper. I, as a Catholic, obey my Church authorities and will continue to do so, in spite of the Irish Times or anything else, in spite of the fact that they may take votes from me or my Party, or anything else of that kind”.

For his part, Dublin’s Catholic Archbishop, John Charles McQuaid, viewed the church’s victory as a sign of who really ran Ireland. In a report on the controversy to the papal nuncio, McQuaid declared that “Protestants now see clearly under what conditions of Catholic morality they would have to be governed in the Republic”. In McQuaid’s eyes, home rule really was Rome rule.

A subsequent attempt by a Fianna Fáil government to introduce a third version of the Mother and Child scheme in 1953 resulted in the hierarchy threating to reignite the controversy by making their detailed objections public by means of an embargoed letter that had been sent to the Irish Press and Irish Independent – but not the Irish Times. A meeting between de Valera and Cardinal John D’Alton resulted in the withdrawal of the letter – but only after de Valera agreed to ditch any plans for maternity education and limiting free infant care to six weeks.

In later decades Bowne outlined his attempts at healthcare reform in his bestselling autobiography Against the Tide, which contained telling descriptions of bishops and politicians enjoying the high life of episcopal palaces and state-funded galas in a country that supposedly couldn’t afford free maternity care.

Following Browne’s death in 1997, information that had been in his possession relating to an allegation of child abuse involving his long-deceased nemesis, Archbishop McQuaid, was published in 1999 – to much consternation – by John Cooney in his masterful biography of McQuaid.

Although at the time this information was repudiated by the Dublin Archdiocese as “conjecture and rumours” its veracity was confirmed in 2011 when the religious affairs correspondent of this paper, Patsy McGarry, revealed that McQuaid had been the subject of several child-abuse allegations that had been belatedly notified to the Commission of Investigation into the Catholic Archdiocese of Dublin. As we continue to unpick our past it’s clear that the obsequious deference to the church that killed the Mother and Child scheme also facilitated graver injustices.

Mark O’Brien is associate professor of journalism history at DCU and the author of The Fourth Estate: Journalism in Twentieth-Century Ireland