CRESTWOOD (MO)

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

April 18, 2021

By Jesse Bogan

CRESTWOOD — In the 1950s, the Archdiocese of St. Louis was on the move, trying to catch up with a flock migrating out of the city in droves. New churches were in demand, particularly in south St. Louis County.

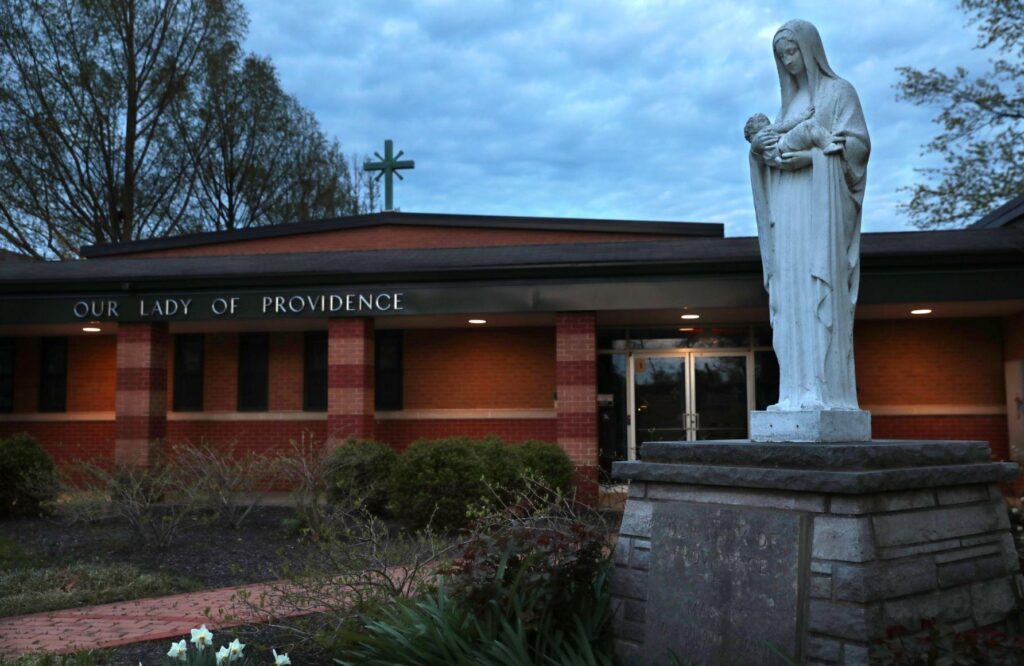

The Rev. Vincent J. Duggan, a former 2nd Marine Division chaplain in the South Pacific during World War II, was called in from a tiny parish in Montgomery County, Missouri, to help. His assignment: transform a farm in the 8800 block of Pardee Road into Our Lady of Providence.

With the help of a group of nuns Duggan recruited from Indiana, the church and school quickly became the spiritual home for hundreds of families. Duggan would stay more than two decades, earning high praise from his congregation, according to an extensive online history of the church that champions each milestone.

To this day, Our Lady of Providence is still active. But it’s faced with a conundrum. In 2019, the archdiocese released a list of dozens of clergy deemed to have substantiated claims of sexual abuse of minors against them. Last month, Duggan’s name was added to the existing list, which victim advocates say is among the least informative in the country.

Apart from his name, the list merely says Duggan was ordained in 1940 and died in 1984. It doesn’t say where Duggan, or the other disgraced archdiocesan priests and deacons, served. Nor are there mug shots.

Still, some old-timers at Our Lady of Providence recognized Duggan’s name. Coming out of church on a recent day with a group of other women, an energetic 96-year-old said she remembered Duggan being out in front years ago, greeting people.

“He was very religious, and he cared for his church. That was for sure,” said the woman, who has attended the church since the 1950s.

Like a few others interviewed there, she didn’t want to be named or spend much time talking about Duggan being added to the list. She was puzzled by the development. She said she hadn’t asked her children about it because they’d all grown up and moved away a long time ago.

“He was very caring,” she added of Duggan. “I don’t know why someone would have an allegation. He’s been dead for a while.”

And he’d been based at other churches, too.

While the archdiocese doesn’t mention service history in its list of disgraced clergy, Archbishop Mitchell T. Rozanski sent letters to the parishes where Duggan worked. The letter to Our Lady of Providence, inserted in the weekly paper bulletin, assured congregants that their baptisms, marriages and confessions offered up through Duggan were still valid.

“As central celebrations of our Christian mystery, God reassures us that those very sacraments — not the officiants themselves — remain true vehicles of grace through Christ,” Rozanski said, according to a copy of the letter.

Rozanski wrote that he “strongly” encourages “anyone who has yet to share their story of abuse to please come forward,” but the letter stops short of saying anything about what landed Duggan on the list, nor the decade of the abuse or the congregation.

“This is a painful time for our Church as we see the names of clergy, some very familiar to us like Father Duggan, accused of behavior that we can barely allow ourselves to imagine,” Rozanski said in the letter. “This is also an important time for our Church as we walk with victims in their pain, and forge a path forward in trying to establish trust once again in those who serve you in the Catholic faith.

“The Archdiocese of St. Louis is committed to the healing and reparation of our Church as we reestablish that trust, continue to ensure transparency, and most importantly, keep our Church safe for our children and those who are vulnerable in our community.”

Public awareness of the clergy sex abuse crisis has led to reforms since the lid was blown off in Boston in 2002. The Archdiocese of St. Louis reports a precipitous drop in the number of abuse occurrences from clergy since the 1970s. But victims continue to come forward. Some of them and their advocates say claims of transparency, in light of the barebones list of publicized names, rings hollow, signaling the organization continues a culture of secrecy.

Ken Chackes, an attorney who has handled more than 100 childhood sexual abuse cases in the St. Louis area, most of them involving Roman Catholic clergy, said he isn’t surprised that more information isn’t shared. He said the archdiocese has always fought tooth and nail to keep records about problem priests out of the public eye, particularly records explaining the decision to defrock, or laicize, a problem priest.

“It goes along with how they’ve always hidden that information,” said Chackes. “They are always worried about the scandal.”

David Clohessy, of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, or SNAP, described the archdiocesan list as the “absolute bare minimum” considering others across the country.

“I don’t know any victim who still attends the church where they were molested,” he said. “This sounds to me like disclosure for public image, rather than disclosure for real outreach.”

Rozanski, through spokesman Peter Frangie, declined to be interviewed by the Post-Dispatch on the Duggan case, the list or anything else about his first nine months at the helm here. When pressed, Frangie said by email: “On the website you will find that the archdiocese is transparent with information regarding those on the list of Clergy with Substantiated Allegations of Sexual Abuse, but also takes into consideration the wishes of victims, families and the faithful in regards to what the archdiocese shares publicly.”

That statement sounded untrue to a man in his 50s, who told the Post-Dispatch that he was the victim whose allegations landed Duggan on the list.

“They never asked me anything about what they can share,” he said. “I don’t know what in the hell they are talking about. Who are the ‘faithful’? These guys are crazy. They never asked my family what they can share.”

‘Necessary first step’

The Roman Catholic Church is hierarchical, with the pope leading the global flock, but there isn’t a universal standard for publicizing clergy with substantiated allegations of child sexual abuse. Since 2002, 158 dioceses in the United States have put out lists, according to BishopAccountability.org.

“There really has been some progress,” said Terry McKiernan, president of the online database. But he added: “The church is still very secretive.”

There is a large variety of lists. He said most are slim and leave out religious order clerics. While St. Louis is among the least transparent, he said, 20 Roman Catholic dioceses in the country still don’t have a list, including Miami, Denver and San Francisco.

“Unfortunately, bishops often value finances and reputation over helping survivors,” McKiernan said.

San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone has “found it not necessary to release a list” because “there are names already made public,” said Jan Potts, a spokeswoman.

Asked if any names haven’t been publicized that should be, Potts said she didn’t know. She said Cordileone, in 2018, announced he was launching an internal review of some 4,000 priest personnel files dating to the 1950s but that the release of any findings was likely slowed by the needs stemming from the coronavirus.

Just 100 miles from San Francisco, Sacramento Bishop Jaime Soto’s list is among the more transparent. Click on any of the names and a warning comes up saying the “content you are about to see may be graphic.” There are mug shots of accused clergy, biographical information, parish assignments and dates, the number, gender and age-range of victims, and the nature of the alleged abuse.

The Sacramento diocese also publicizes a list of 22 common questions, including “How much has the diocese paid to settle claims of sexual abuse?” and “When will this be over?”

“We cannot think of this as something that will pass,” the Sacramento diocese says. “The depth of the sin committed and the lasting nature of the harm done to victims requires that we make atonement part of our spiritual life from this point forward.”

Asked what motivated him to be more transparent about the diocesan priests, Soto told the Post-Dispatch in a prepared statement:

“I am committed to confronting the past and the shameful sins and crimes of clergy sexual abuse. If I expect to receive the mercy of Jesus, I have to walk in the light of Jesus. A necessary first step in owning the past and atoning for it is to make a thorough and public accounting of it; the list represents my attempt to do that.”

Collectively, the nation’s bishops are quiet on the issue.

Bishop James Johnston Jr., of the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph, is the current chair of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops Committee for the Protection of Children and Young People. His spokeswoman, Ashlie Hand, said she “won’t be able to offer an interview.” She recommended emailing questions.

Asked in writing about why there are differences in the various lists around the country, and what impact that has, Johnston, through his spokeswoman, didn’t respond.

Selective history

Duggan’s alleged victim told the Post-Dispatch that he was motivated to come forward because the priest’s name wasn’t initially on the St. Louis archdiocese list. He said he was tired of people putting Duggan on a pedestal.

“He was a great front man,” he said. “But behind the scenes he was nasty.”

He said Duggan abused him in the 1970s, when he was a grade school student at Our Lady of Providence. He said his mother had asked Duggan to teach him about sex education. He said Duggan initially masturbated in front of him in the rectory. The abuse escalated from there, lasting about two years.

Later, as a teenager, he said, he was twice treated for attempting suicide by eating bottles of pills. As an adult, he moved away from St. Louis and retired early. He came from a family with resources. He said he’s been in and out of drug and alcohol treatment throughout his adult life.

He said he shared some of his mental health records from years of therapy to support his claims to the archdiocese. He said he and a sibling also provided dozens of names of people to contact, including former priests who used to come to their house when they were children, nuns at the school and other family members.

He said the archdiocese told him that he was the first person to make a claim against Duggan, one reason why the internal investigation lasted months. The man said he initially didn’t come forward to get paid, but that the archdiocese eventually brought it up. Accepting an undisclosed settlement came with an agreement that he wouldn’t later sue the archdiocese.

“I signed it because I don’t care about the money,” he said. “If there are other victims out there like me, they need to know that it’s OK to come forward about Father Duggan. He was bad. Unfortunately everyone makes him out to be this wonderful god, this wonderful priest.”

It’s been years since he’s gone inside Our Lady of Providence, where a large room or hall, at least until recently, was named after Duggan. An extensive online parish history still celebrates Duggan as its founding pastor. He led the first Mass there in 1954 and quickly ramped up from there. When he announced his retirement in 1977, Duggan wanted to spend more time teaching at the parish school. There was a party for him.

“In addition to giving several gifts to Father from the students, a representative from each grade read an appreciation statement to him, recognizing the special person he had been to them,” the history says.

The history says his replacement focused on adult education and prayer, and also encouraged the laity to take a more active role in governance. Recently contacted by the Post-Dispatch, Parish Council President Mark Murray IV, a lawyer, declined to comment, instead referring questions to Frangie, the spokesman for the archdiocese.

Apart from Duggan, three others on the archdiocese’s list of disgraced clergy served at Our Lady of Providence. The Rev. Don G. Brinkman, a former director of vocations for the archdiocese, was at the parish from 1975 to 1976 and again for a period in 1987; the Rev. James McLain was there from 1959 to 1960; the Rev. Robert F. Johnston, was pastor from 1996 to 2002.

All four of their names — Duggan, Brinkman, McLain, Johnston — are honored in the online parish history, including some of the obstacles they overcame, but there’s nothing mentioned about substantiated claims of sexual abuse made against them. The lengthy narrative concludes:

“While this account summarizes important events of the past, which we can all enjoy, it is our present and future that we are compelled to consider. Let us pray that we are inspired by the trends of the past in order to secure a bright future for this special Roman Catholic family. We will continue this account as more of our history is in the making.”

‘If there are other victims out there like me, they need to know that it’s OK to come forward about Father Duggan. He was bad.’

DUGGAN’S ASSIGNMENTS

1940: Ordained, attended Kenrick Seminary

1940-1943: Our Lady of Mount Carmel, St. Louis

1943-1946: 2nd Marine Division chaplain, South Pacific

1946-1948: Our Lady of Mount Carmel, St. Louis

1948-1953: Church of the Assumption, St. Louis

1953-1954: Resurrection, Wellsville, Missouri

1954-1977: Our Lady of Providence, Crestwood

1978-1983: Our Lady of Providence, pastor emeritus

1983-1984: (retired) Mary Queen and Mother Nursing Center, Webster Groves,

Source: St. Louis Post-Dispatch, BishopAccountability.org