Breaking the Silence: Second Terre Haute Man to Join Abuse Lawsuit

Recounts Time with Priest

Terre Haute Man Becomes 13th to File in Suit against Harry Monroe

By Stephanie Salter

The Tribune Star

August 19, 2006

http://www.tribstar.com/local/local_story_231231544.html

[See also Lawyers

on Both Sides of Abuse Case Fight 'Zealously' for Their Clients, by

Stephanie Salter, Tribune Star (8/19/06).]

TERRE HAUTE — In the dim light of a downtown coffee house, the years

and troubles are undetectable. "John Doe CD" looks like any

thirtysomething ducking in for a cup of joe on his way to or from work.

Outside in the bright light of day, his still boyish but worn face tells

another story:

His first rehab program at age 15; three jail sentences for drug possession,

including nearly a year for methamphetamine; a divorce; a child with another

woman; and, these days, two different anti-depressants, intensive outpatient

therapy at Hamilton Center and AA meetings every day — as ordered

by a judge.

|

"It isn't something that just happens and goes away," he said.

"It comes back when you least expect it. It comes back in negative

ways."

What the young man says happened many years ago was child sexual abuse

by Harry E. Monroe, once a priest and youth minister at St. Patrick Church

in Terre Haute. Thursday, when the former altar boy's attorney, Patrick

Noaker, filed a suit in Vigo County Superior Court, Doe CD became the

13th man to formally accuse Monroe of molesting him as a minor.

The Archdiocese of Indianapolis also is accused of enabling the alleged

crimes. Spokesman Greg Otolski said the office could not comment on any

pending litigation, and he could not speak to "what happened 30 years

ago." But he reiterated that the Archdiocese is aggressive about

following up on reports of sexual misconduct and continues to offer help

to anyone who asks the church for it.

|

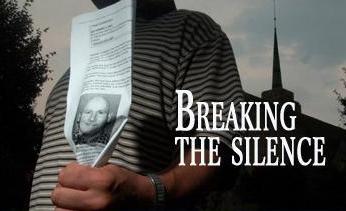

| He was an altar boy: "John Doe CD" is the 13th man to file a civil lawsuit for alleged child molestation against former priest Harry E. Monroe. He says Monroe sexually abused him when he was an adolescent at St. Patrick Church (in background) in the early 1980s. Tribune-Star / Joseph C. Garza [scanned from print edition] |

"If anybody came to us about any kind of crime they said was committed,

we'd immediately call the police ourselves," he said.

All 13 plaintiffs are adult men identified by the legal pseudonym "John

Doe" with relevant initials after. They knew Monroe as "Father

Harry," ordained in 1974 and assigned over the next 10 years to parishes

in Marion, Vigo and Perry counties.

In June, the complaint of another former St. Patrick's youth, "John

Doe WC," became the first Noaker filed here. The lawyer said at least

six Terre Haute boys and their families complained in writing of sexual

abuse to the Archbishop of Indianapolis when Monroe was at St. Pat's.

One of the boys, Daniel Limcaco, died in 1983, an apparent suicide. His

parents, Melissa and Oscar Limcaco, recounted their son's and their ordeal

in a Tribune-Star story last year. While they believe Daniel's death was

related to his alleged abuse, they do not plan to file a lawsuit.

Now 59, Monroe was a functioning priest until 1984 when, Archdiocese officials

say, his priestly faculties were revoked. During that decade, he served

in three Indianapolis parishes, then St. Patrick's, was placed on leave,

then assigned as co-pastor of three small parishes in Tell City, Troy

and Cannelton.

He has not been laicized, or defrocked, an action only the Vatican can

take.

For several years Monroe has lived in Nashville, Tenn., and, until this

past winter, worked in a health-care facility. He no longer has a listed

telephone number. Last month, an Indianapolis Star reporter spoke briefly

with him in the driveway of his Nashville home, but the former priest

said he had been advised by his attorney to say nothing.

Monroe's Indianapolis lawyer Bryan Lee Ciyou did not respond to a request

for comment. In court filings his client has denied the accusations.

Staring at a copy of Monroe's Tennessee driver's license photo, John Doe

CD managed a tight smile.

"He's lost all his hair," he said.

In 1979, when Monroe arrived at St. Pat's, he was barely 30 and drove

a motorcycle as well as a car. Often, former parishioners say, he would

take the adolescent schoolboys for rides on the bike and on camping trips

and other outings in his car.

"Father Harry seemed to pick out the people whose parents were divorced

or who didn't have fathers around," said Doe CD, who was one of those

children.

His parents were divorced, his father "worked all the time"

and rarely visited, and his mother held down two jobs to support her kids

and pay for Catholic school tuition. The attentions of a young, athletic

priest seemed like an answered prayer to her.

"He was a man of God. She didn't worry about me when Father Harry

took us out, even when it was late," CD said.

To the boys in Monroe's care, spending time with the priest was both fun

and uncomfortable.

"He came at you more as a friend than as a priest," CD said.

Early on, Monroe held evening education sessions in the St. Patrick rectory,

the young man said: "He'd talk to us about God, but a lot of it was

sexual stuff. He'd ask us if we'd ever done this or that and tell us to

talk about it."

Then Monroe began taking a few boys to play racquetball at a tennis center

in the city.

"Afterwards, he'd go get beer for us and whiskey for him, and we'd

just cruise around in his car drinking or go back to the rectory,"

CD said. "I was 12 years old and drinking with Father Harry. I remember

one time, Father Joe [Wade] saw us carrying beer to Father Harry's room.

He didn't do anything."

Wade, who was pastor at St. Patrick's during Monroe's time there, quit

the priesthood many years ago. He did not return a voicemail left on his

home telephone in Indianapolis.

CD said it was late one night after playing racquetball with Monroe that

the priest allegedly molested him at the tennis club.

"It was just me and him. We got in the hot tub and, at first, it

was just like horsing around," he said, but the man began to fondle

the boy and himself.

"Just the way he came at you, it was like there wasn't anything wrong.

I didn't know what to think," CD said. "He did ask me if I liked

it, how I felt … he was masturbating."

CD said he was about 12 or 13 at the time. Almost in a whisper he said,

"That was my first orgasm."

In the ensuing months, the young man said, he was besieged by conflict

and confusion. Along with the group drinking sessions, he said, Monroe

introduced some of the boys to marijuana.

"The first time I got high was in the church basement at St. Pat's,"

he said.

|

|

| The details: Minnesota attorney Patrick Noaker (right) talks with deputy clerk Annette Lindeman after he filed a lawsuit on behalf of "John Doe CD" against the Archdiocese of Indianapolis and former priest Harry Monroe on Thursday at the Vigo County Courthouse. At top, Noaker talks with Terre Haute Police Department detectives Rick Decker and Jim Richardson after Noaker's press conference Thursday at the Vigo County Courthouse. Tribune-Star / Joseph C. Garza [scanned from print edition] |

Echoing what the Limcacos said they learned from their son before he

died, CD said Monroe told the boys their parents would prefer they experimented

with marijuana and alcohol in the safety of the priest's supervision rather

than on their own.

One night after a round of drinking, CD said, Monroe dropped off the only

other boy in the car and began to head away from CD's neighborhood. He

spoke overtly of sexual acts he liked and wanted to perform on CD, the

young man said.

"By then, I was having these feelings," he said. "You know,

'This wasn't right.' We were at the stop sign at Brown and College, and

I just said, 'Take me home.' I pushed over as far away from him as I could

against the door and told him to take me home. He did. It was 12:30 at

night. I went and woke my mom up and told her."

CD's mother consulted an attorney friend who knew of other complaints

in the parish against Monroe. Wade informed then-Archbishop Edward T.

O'Meara, and several boys were advised to send letters to the Archdiocese.

"I sat and wrote it all out and sent the letter to the Archdiocese,

and a letter came back, but I don't remember what it said," CD said.

After Easter 1981, Monroe was suspended from priestly duties at St. Patrick's,

then left the parish.

"You know what kills me?" CD said. "Father Joe and Sister

Ann Carver — after they'd sent Father Harry away — they pulled

me out of class over to the rectory and told me I should write him a letter

and tell him I forgive him. I couldn't believe they did that. I couldn't

believe they had the nerve … They almost made me feel like it was my fault."

CD said he was so angry he told the pastor and nun "there was no

way" he would write Monroe. After that, he said, he could no longer

even speak to the sister. Soon, "I quit going to church and I stayed

away for years. I still pretty much do."

Carver left her religious order around 1983 and moved to Massachusetts.

No one answered a telephone listing for her, and there was no voicemail.

Still in early adolescence, CD said he began to drink heavily, use drugs

when he could get them and neglect his school work. He was depressed and

anxiety-ridden.

"I had problems, thinking, 'Am I a homosexual?' I became very promiscuous

— to prove to myself," he said. Even though he "always

knew there were others" at St. Pat's who'd had similar experiences,

"I figured I had done something to cause him to come after me. There's

a lot of shame that goes with that, embarrassment."

He entered his first substance abuse rehabilitation program at 15 and

abandoned school. Later, as an adult, he managed to get his G.E.D.

CD currently works in a blue collar job that occupies his nights. His

days are filled with therapy and 12-step meetings and a little time with

his girlfriend of 18 months. He tries to be a father to his grade school-age

son, he said.

Before the month is over, CD again will face the judge and learn if he

is allowed to remain in a supervised work-parole program or has to serve

out the last of his sentence behind bars.

Whatever happens to him personally, he said, he feels "it was just

the right thing to do" to join the other men in their lawsuits.

"When I realized there was more than just me, more people out there

that haven't said anything and are just living with it … It would probably

be best to admit it and open up to it. If it's all kept in the closet,

nothing's going to be done about it. I think that's what the church has

done, keep it in the dark," he said.

Asked how he responds to people who say it's unfair to the church today

to keep dredging up old allegations of past abuse, CD said:

"They never had to go through it. They don't understand it sticks

with you, it scars you. The effects — homosexuality, drug use, alcohol

abuse, shame, being afraid you'll be ostracized because of it … He [Monroe]

should be held responsible for what he did, and the Archdiocese covered

it up from the get-go. You would have figured — those letters to

the archbishop — they would have done something."

Still estranged from the Catholic Church, he said he is of no mind to

leave the past alone, especially if it means alleged abusers — no

matter how old they are or in what jobs they work — might be free

to victimize other children.

"It has to stop, whatever it takes. It should have stopped a long

time ago. If it had been any other person in any other field," he

said of Monroe, "they'd have arrested him."

Stephanie Salter can be reached at (812) 231-4229 or stephanie.salter@tribstar.com.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.