Sins & Silence

Victims Recall Abuse:

Men Recount How Priests Befriended, Abused Them

By Mary Nevans-Pederson

Telegraph Herald [Dubuque IA]

March 6, 2006

http://www.thonline.com/story_news_frontpage.cfm?ID=110755&

CFID=157083&CFTOKEN=8a73426fc7dbefd1-65345BD8-983C-EDB2-246953C7E41AF0A1

[See the main page of the Sins & Silence series for links to all the articles and letters to the editor.]

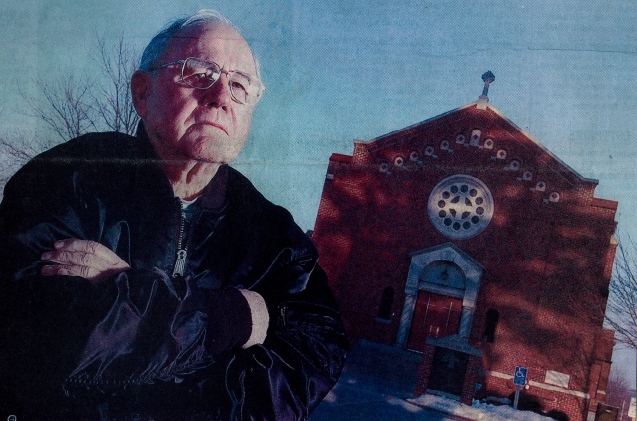

| "I didn't tell anybody. I thought I was the only one at

the time." Larry Kramer, recounting sexual abuse by the Rev. Robert Reiss during the 1970s |

Mel Loes tried to think about something else. Father Patnode was doing

it again.

As he did many mornings, Loes, then 16, walked to St. Joseph Catholic

Church in Key West, Iowa, to assist at Mass for the Rev. Joseph Patnode.

And as had happened many of those mornings before Mass, Patnode molested

the altar boy.

Loes had grown used to it.

|

| Mel Loes says he was sexually abused by

the Rev. Joseph Patnode between 1939 and 1941 at St. Joseph Catholic

Church in Key West, Iowa. TH: Jeremy Portje. |

Shortly after Patnode came to St. Joseph's as pastor in 1939, he started

abusing Loes. It usually happened before Mass.

On another occasion, Patnode had the teenager drive him to Preston, Iowa,

for an overnight stay at St. Joseph Church, where Patnode previously was

assigned. That night, in a rectory bedroom, he assaulted Loes.

After the first time he was abused by Patnode, Loes went home and told

his mother, "He's fooling around with me."

He still remembers what his deeply devout mother said:

"Father Patnode wouldn't do that."

The teenager told no one else about the abuse. He thought he was Patnode's

only victim.

"I couldn't do anything about it," said Loes, now 82. Years

later, he learned that Patnode had abused other teenage boys. At least

10 men, now in their 70s and 80s, have told Loes that as teens they were

molested by Patnode.

An ostensibly innocent but telling entry appears in a parish history book.

It states that Patnode "helped many boys by keeping them at his rectory

and giving them jobs to do."

By the time Loes graduated from Loras Academy in 1941, the pastor had

lost interest in him. "He had other, younger playboys by then,"

he said.

Loes joined the Air Force in 1943 and served as a tail-gunner on a B-17,

flying missions over Germany.

He returned home in 1945 and soon married the sweetheart who had waited

for him. Mel and Georgeann Loes had three children, who gave them grandchildren

and great-grandchildren.

The memories of his abuse faded in the face of war's more horrific images.

During this time, Loes received a shocking phone call from a friend.

"He told me Father Patnode was abusing his two sons and asked what

he should do. I told him that (Patnode) had done it to me, too. This was

a good Christian man who was so upset. He went to Archbishop (Henry) Rohlman

and Patnode was gone soon after that," Loes said.

Patnode was next assigned to be chaplain of the Mercy Sister Novitiate

in Marion, Iowa, where he worked until he retired in 1964.

"I thought that was great. He wouldn't bother the nuns," Loes

said.

But in October 2002, at a public diocesan gathering of priests in Waterloo,

a priest told Loes that although Patnode was assigned to a facility full

of women, he continued to befriend young males and "take them to

a cabin."

The story Mel Loes tells is similar to those told by scores of other men

and women. The victims usually came from devoutly Catholic homes—homes

where priests were revered and often invited to family functions.

Although Loes had a stable family situation, many of the abused youngsters

came from families disrupted by illness, death, poverty or alcoholism.

Struggling mothers and fathers were happy to push their sons into the

circle of friendship and mentoring offered by an amiable priest who took

an interest in them.

The priests often enlisted teenage boys to work as their drivers. Victims

of Patnode, William Roach and William Goltz claim that the priests either

abused them while en route or after driving to a destination.

The assaults took place in church sacristies, rectories and basements,

in remote woods and rock quarries, in cabins and confessionals.

Priests assigned to parish schools called students into their offices

or the school basement, where they abused them.

Didn't recognize abuse

Daniel Kortenkamp was just 13 when the Rev. Robert Swift began to abuse

him.

Swift was an assistant pastor Sacred Heart Parish and a chaplain at Mercy

Hospital, both in Oelwein, Iowa.

"He would put his hands down our pants and squeeze and rub us. He

said he wanted to see if we were developing normally. He called it 'sex

education,'" said Kortenkamp, 68, of Stevens Point, Wis.

|

| Daniel Kortenkamp |

This happened at the hospital and in the church before Mass, Kortenkamp

said.

Kortenkamp, who went on to become a professor of psychology at the University

of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, said he "never experienced any injury

from my abuse."

It was 50 years before he told anyone about it.

"I was very naive. My friends and I thought at the time that he was

just 'queer' and that's what queers do. Of course, Father Swift's behavior

was sexual abuse," he said.

Having said that, Kortenkamp is quick to point out that his four decades

of work in clinical psychology have taught him that "homosexual men

are no more likely to be sexual abusers of children than are heterosexual

men."

Boy befriended by priest

Larry Kramer was being raised by relatives when the Rev. Robert Reiss

came into his life. Kramer's mother had died in a car accident and his

father was an alcoholic.

To pay his tuition, Kramer worked at Visitation Parish School in Stacyville,

Iowa.

One hot day in the 1970s, Reiss invited the teenager into the church rectory

for some lemonade. They went upstairs to the priest's bedroom, where Reiss

had sex with Kramer on the floor.

|

| Larry Kramer |

"I had to look at a picture to get through it," Kramer said,

his voice quavering nearly 30 years later. It was the first of many such

assaults by Reiss.

"I didn't tell anybody. I thought I was the only one at the time

and my uncle, who I lived with, was close to Father. There were rumors

around town, but people were divided about (Reiss)," said Kramer,

who now lives in Byron, Minn.

A few years later, Reiss was given a one-year leave of absence and was

then reassigned to other parishes.

"When he was transferred away, I was never so relieved in my life,"

Kramer said.

Reiss next served as pastor in Sabula and Green Island, then in North

Buena Vista.

In 1990, Reiss was involved in a bizarre incident while living at Immaculate

Conception Parish in North Buena Vista. He befriended an ex-convict who

kidnapped a Maquoketa girl and threatened to rape her. After the girl

escaped, Michael Cavins, 25, drove to the church, where Reiss hid him

from authorities.

Three days later, Dubuque Archdiocesan leaders announced that Reiss had

requested a leave of absence. His activities as a priest were restricted

and in 1997 he was defrocked by the Vatican. He died last year in Mexico

at age 75, and authorities there investigated his death as a murder/robbery.

How cases were handled

Dubuque archdiocesan officials handled each of these cases differently.

• In 2002, when Mel Loes finally told the archdiocese about his

abuse, they admitted they had heard other accusations against Patnode.

Loes volunteered to be a part of Dubuque's archdiocesan Review Board -

a confidential, consultative body that examines all claims of sexual abuse

of minors in the archdiocese.

Less than a year later, Loes quit the board, saying, "I object to

the confidentiality. To me, it means cover-up." He claims the church

continues to "hide priests behind Canon Law" and has turned

his back on the church, which was part of his life for some 80 years.

• Daniel Kortenkamp said working with church officials has been

"like pulling teeth."

Three years ago he made abuse accusations to the archdiocese about Swift

and the Rev. Thomas Knox, who also worked at Sacred Heart in Oelwein.

Correspondence from archdiocesan officials indicated they were already

aware of abuse claims against both priests. Yet, when the archdiocese

published a list of accused priests in January, neither man's name was

on it.

"Then I noticed that the table only listed those with 'public accusations,'"

he said.

Kortenkamp wrote a letter to the Telegraph Herald naming the priests as

abusers. A few weeks later, the archdiocese added the priests' names to

the list.

However, Kortenkamp did praise the archdiocese for making the list public.

• At first, Larry Kramer was bitter about his abuse and angry that

his abuser was allowed to minister in parishes for years before he was

removed.

Kramer is satisfied with how the current archdiocesean administration

handled his case when he approached them in 2002.

"I met with the archbishop (Jerome Hanus) and the vicar general (Monsignor

James Barta) and they believed me right away. They both apologized to

me for what (Reiss) did," he said. The archdiocese has paid for his

therapy treatments since then.

"After all, there are different people in (archdiocesan administration)

today. They didn't hurt me," Kramer said.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.